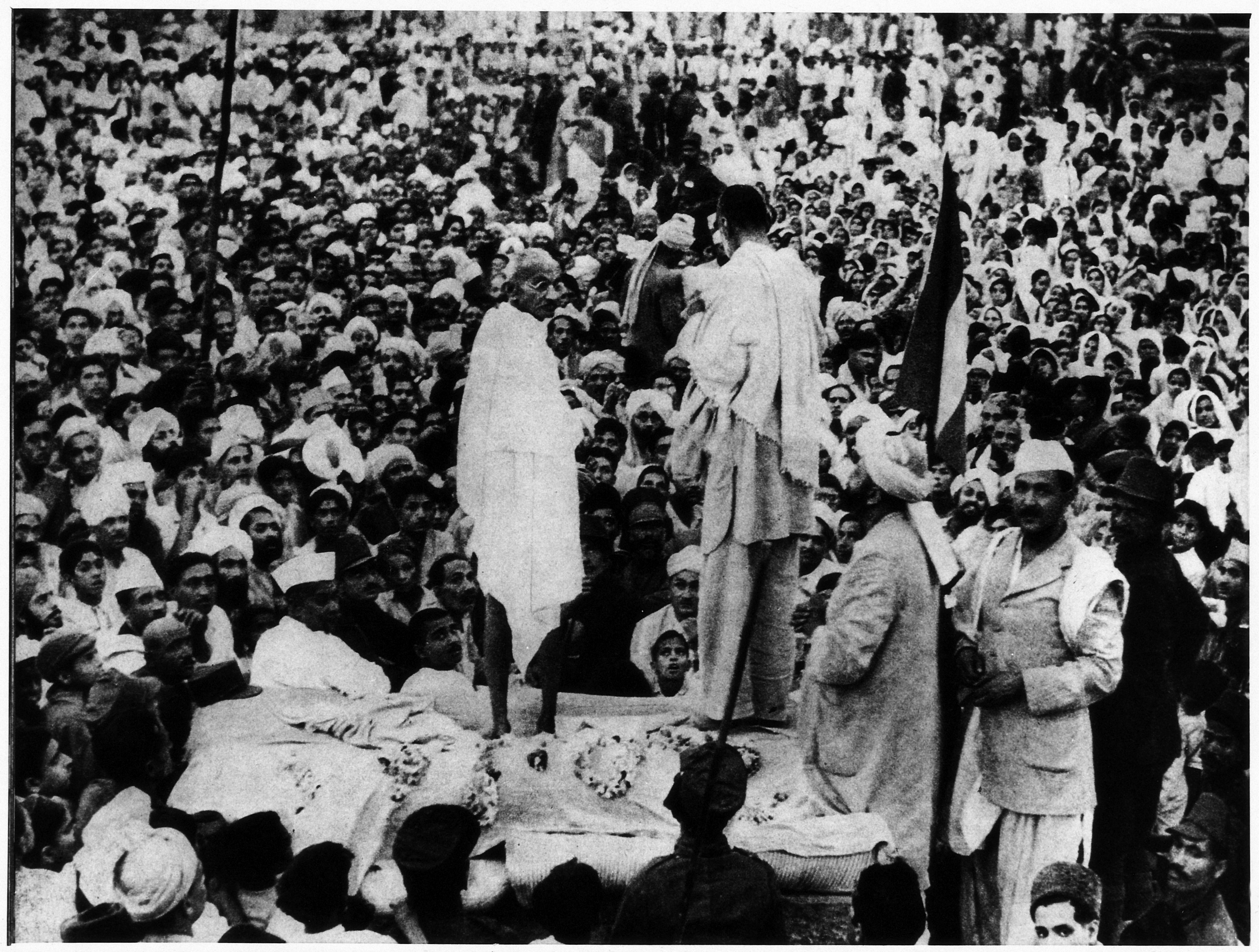

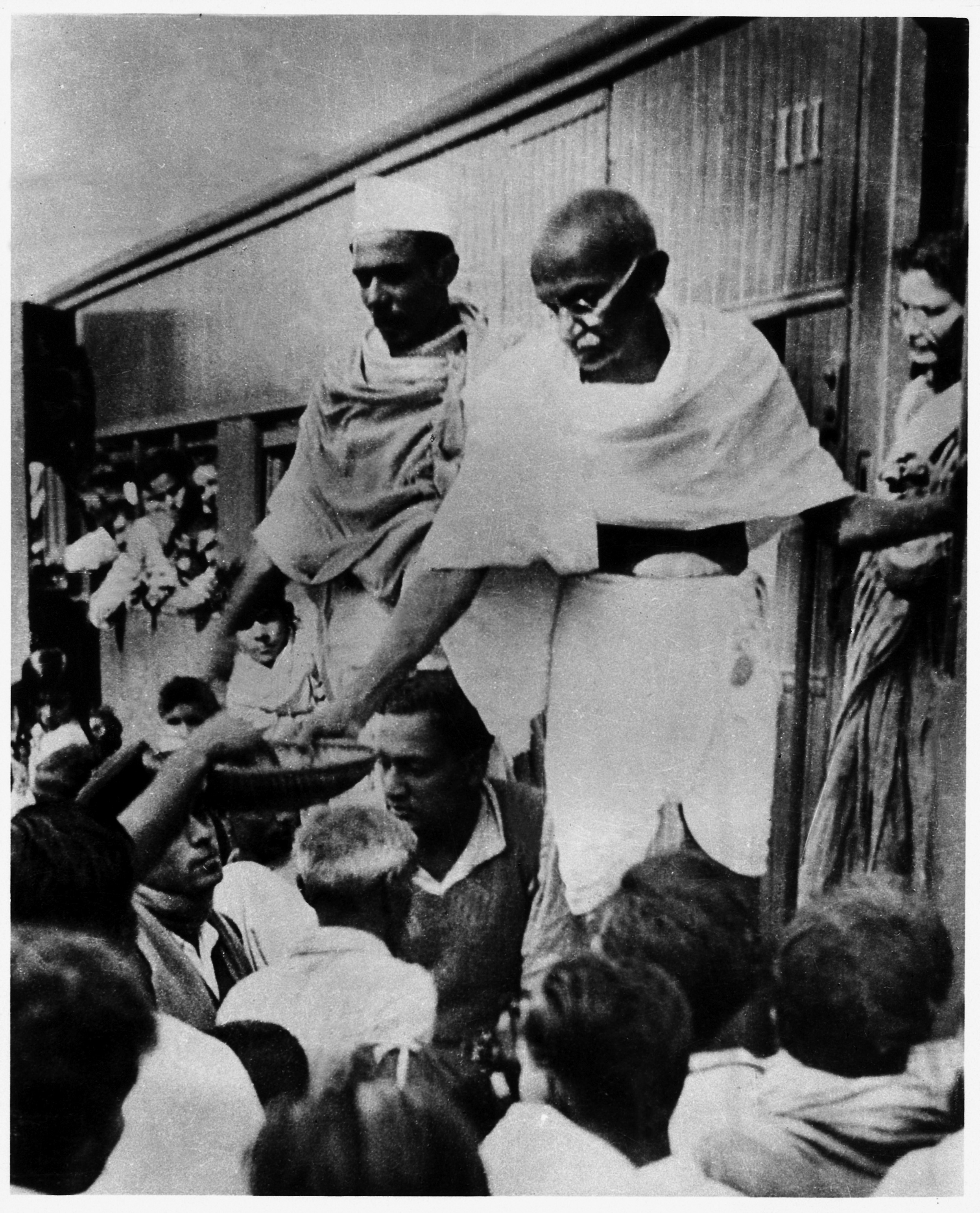

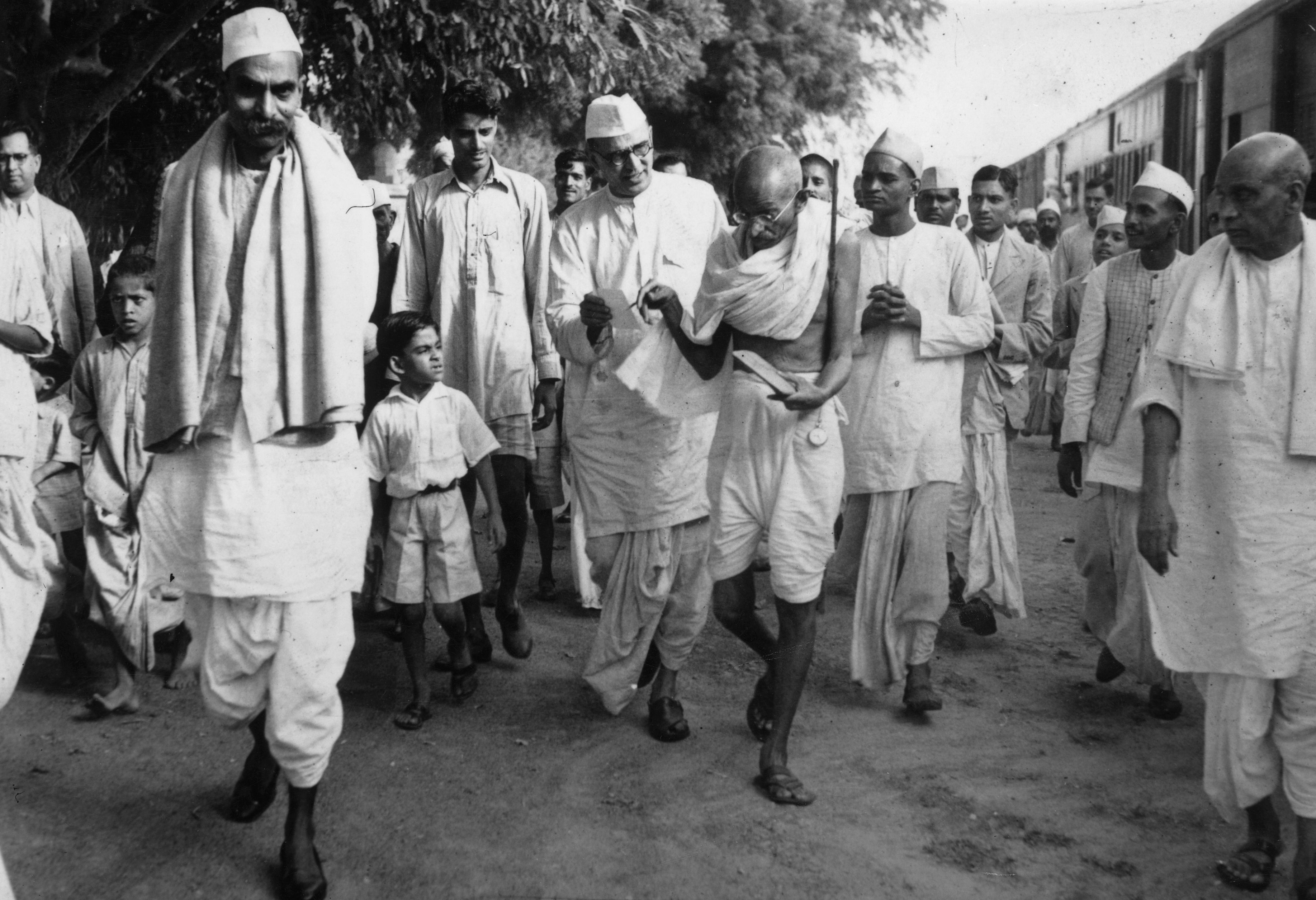

Hyderabad: Under Mahatma Gandhi’s able leadership, the national movement had eroded imperialist hegemony, crumbled the pillars of the colonial structure and reduced British political strategy to a mess of contradictions. However, on the other hand, as a result of extreme animosity between communities, rivers of blood were to flow. In the period of absolute terror, which, by some estimates, saw more than a million killed, and over 14 million people forcibly relocated.

Though, Gandhi denounced the communal violence in unequivocal terms, today’s excessively intemperate era of historical revisionism, it has become way more fashionable than ever to hold Gandhi responsible for the Partition of the country in 1947.

Moreover, in this age of intense vulgarization of politics, there is a dangerous tendency to lionise his assassin Nathuram Godse, and to brand Gandhi’s assassination as an act of retribution carried out by a ‘true Indian nationalist’.

Further, two essential questions - Could Gandhi have done anything to stave off the partition of India? Why could not he prevent the terrible massacres and the mass migration of the minorities in 1947?

Historians have been grappling with these questions ever since; and though there can be no finality about the answers; yet, we can try our best to form a reasonably clear picture in this regard. But for a just appraisal of these questions, it is necessary to see them in their true historical perspective and to contextualize their historical juxtaposition.

To answer the aforementioned two questions— if Gandhi could have staved off the Partition, or at least done something, anything for that matter, to check or prevent the ensuing blood-shed — we need to focus on two things: First, the actual rootedness of this communal violence. And, secondly, we need to understand as to why had the demand for Pakistan become irrevocable and irreversible for the League in general for M.A. Jinnah in particular?

By early 1946 the Imperialism–Nationalism conflict, being resolved in principle, receded from the spotlight, more or less. The stage was then taken over by the warring conceptions of the post-Imperial, post-Colonial political order held by the British, the Congress and the Muslim League — a tripartite struggle of sorts, for the spoils of the Swaraj.

The Congress and the League represented two contradictory urges. The Congress stood for democracy, socialism and a common Indian nationality; the League’s rationale was to promote the interests of Muslims in India as a separate political entity and nation – the ‘other’ nation to be precise.

Though, at times, Jinnah spoke of his desire for a settlement with the Congress, albeit on his own terms: a weak centre, complete autonomy for the provinces, shares of the Muslims in the services, elected bodies and cabinets to be fixed by statute, and the like.

To Jinnah’s perennial questions, which, though, sprouting over sixty years ago with Syed Ahmed Khan, yet fructified now under Jinnah: “What would be the position of the Muslim community in a free India? How Muslims would fare in a free India?” there was only one possible answer which Mahatma Gandhi could offer: “they would fare no better or no worse than the other communities.”

For M.K. Gandhi, or for any other mainstream national leader of the age for that matter, there was no reason to doubt that in a free India political parties would follow communal affiliations and that social or economic issues would not cut across religious divisions. But this could not, and would not, suffice Jinnah’s political ambition. Therefore, he continued to plough his very own singular furrow and chose to stick fast with his ‘Two-Nation’ Theory, and continued to insist on Partition.

Whereas Mahatma Gandhi, on the other hand, outrightly rubbished M.A. Jinnah’s two-nation theory as an untruth; for in his dictionary there was no stronger word. Gandhi’s first reaction to the two-nation theory and the demand for Pakistan was one of bewilderment, almost of incredulity. To him, it was contrary to the good sense.

“How far was the Indian National Congress responsible for the Partition of the country in 1947?”

In Mahatma Gandhi’s view, the Independence-Partition duality reflected the success-failure dichotomy of the anti-imperialist movement led by Congress. In his estimation, the Congress had a very clear cut two-fold historical task — structuring diverse classes, communities, groups and regions into a nation and securing independence from the British rulers for this emerging nation.

To him, the Congress had both succeeded and failed at the same time in realizing this twin task. From his perspective, while the Congress succeeded in building up nationalist consciousness sufficient enough to exert pressure on the British to quit India, it could not complete the task of welding the nation and particularly failed to integrate the Muslims into this nation.

To Mahatma Gandhi, it was this contradiction — the success and failure of the national movement generally, and that of the Congress specifically — which was reflected in the other contradiction — Independence, but with it Partition.

Mahatma Gandhi was convinced, a little naively though, that the communal tension however serious it seemed in 1947 was a temporary phase, and that the British had no right to impose partition ‘on an India temporarily gone mad’.

But his noble plea that there should be ‘peace before Pakistan’ fell on deaf League ears. Therefore, blaming the Mahatma for the Partition and the attendant carnage, and, even more outrageously, lionising his assassin for righting an ill-perceived historical wrong, and is the worst form of historical revisionism we as a society and nation could, or would, commit.

In 1946-47, India appeared to be sliding into an undeclared civil war. To Gandhi, as we know it, to divide India was to undo the centuries of work done by Hindus and Muslims; Gandhi’s soul rebelled against the very idea that Hinduism and Islam represented antagonistic cultures and doctrines, and that eighty million Muslims had nothing in common with their Hindu brethren.

In Gandhi’s opinion, ‘the Muslims must have the same right of self-determination that the rest of India has. We are at present a joint family. Any member may claim a division.’

Arguably, it is because of Gandhi’s this ‘agreeing in principle’ to the demand of Pakistan and Partition, that people, like John Vincent, of Bristol University, hold Gandhi responsible not only for the Partition but also for the ‘shedding of innocent blood during the massacres’, which occurred in the aftermath of the partition of India in 1947.

On the other hand, the ‘Pakistan idea’ sold fast with the Muslim community. The Muslim middle class, which for historical reasons had been left behind in the race for the plums of government service, trade and industry, was attracted by the idea of a sovereign Muslim state.

Thus, ‘the idea of Pakistan’ – held out as a Morean Utopia of sorts to the lay believers – not only promised the dawn of a new socio-political-economic era in the new land of purity, but also guaranteed independence from both the ‘foreign’ British and, more so, from their ‘historical arch-rivals’, the Hindus.

This Pakistan idea, for the first time, seemed to satisfy the religious emotions as well as the political instincts and ambitions of the Muslim middle class. The vision of a sovereign Muslim state in India was reminiscent of the past glories of Muslim rule; it was too fascinating a prospect not to catch the popular imagination.

When communal emotions ran this high, with too much at stake for both the sides, Mahatma Gandhi’s voice, once so powerful, was drowned in a deafening din of communal recriminations by madding bigots on both sides. And then, on 30th January 1948, finally silenced forever by a fanatic’s bullet. Forever? Maybe not; For we, the humanity, rely on Gandhi even decades after his death and long after his supposed lapse into political irrelevance.

Also read: Govt scraped section 370 due to firm determination: Rajnath Singh