Hyderabad: The advent of cooperatives in India dates back to the early 20th century. Inspired by the pioneering examples in Europe like those of Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers in England of 1844 and of Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen founded Credit Union of 1864, the British Indian government enacted the first cooperative Act 1904, as a central subject, facilitating the organization of the rural cooperative credit societies to help the beleaguered farmers.

Following the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms of 1909, the government brought the subject, in 1912, under the provincial governments’ legislative competence. It is another story that the British colonial plunder itself pushed the farmers into distress and the government felt it necessary to arrange some institutional mechanism for farm credit in order to prop up farmers to incessantly collect the land revenue from them.

Whatever be the British compulsions to bring them into being, the core values of the cooperatives included: democratic functioning, self-help, honesty, transparency and above all, collectively working towards the welfare of all their members.

Inherent weaknesses

Unfortunately, the cooperatives in the country, though with the continued support from the successive governments of free India, too, could not achieve these goals. The recent trends of the cooperatives, particularly the jerks of some Urban Cooperative Banks (UCBs) like the Punjab and Maharashtra Cooperative Bank (PMC) have once again evidenced the deep-rooted crisis in them requiring immediate correctives to stop further such catastrophes.

The cooperatives' inadequacies were found way back in 1951 when the All India Rural Credit Survey report brought out the truth that the credit supplied by them during their five decades of existence was too inadequate and they had been ridden with many deficiencies.

The sixteen State Cooperative Banks then existing (in 1951 - 52) had a meager deposit base of Rs 21.02 crore and had supplied a credit of Rs 24 crore. Similarly, the six central Land Mortgage Banks lent some equally insignificant amount compared to the actual need. Again, the bulk of this credit went to benefit the landed gentry, not the weaker sections.

Similarly, the committee on direction on Rural Credit Survey (of Gorewala and others) of 1955, too, has exhaustively listed their functional, structural and administrative weaknesses. In particular, the inefficient internal administration with untrained staff, control of vested interests and the external factors like the all-round illiteracy, the chronic deficiency of roads, storage and other economic requirements and such other things hindered the achievement of cooperative goals.

However, the later efforts of the government through the development of credit cooperative structures helped the sector play a key role in agricultural credits. At one point the cooperatives, whatever their inadequacies, became synonymous with institutional credit. Since the inefficiencies continued despite measures, their relative importance has considerably eroded.

The current share of cooperatives in agriculture credit is less than 15% with the remaining 85% supplied by the commercial banks (79-80%), RRBs (5%) and some 1% by the microfinance.

Widespread network

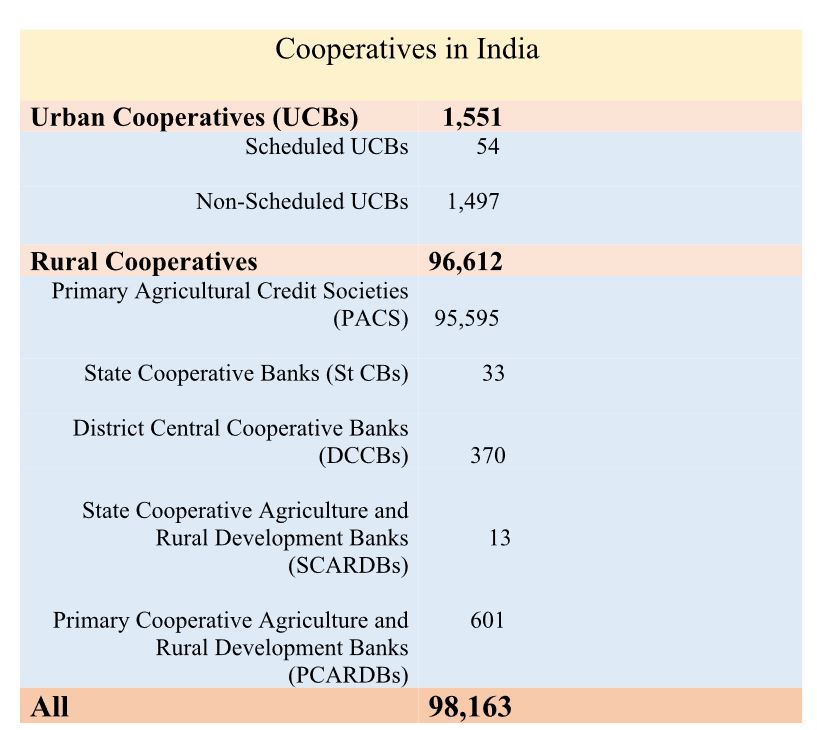

Currently, the cooperatives work through their 98,163 outlets across the length and breadth of India. Of them, 1,551 are urban cooperatives comprising two types: scheduled UCBs (54) and Non-Scheduled UCBs (1,497). Remaining 96,612 are rural cooperatives consisting of Primary Agricultural Credit Societies -PACS (95,595), State Cooperative Banks -St.CBs (33), District Central Coop Banks -DCCBs (370), State Cooperative Agriculture and Rural Development Banks - SCARDBs (13) and Primary Cooperative Agriculture and Rural Development Banks - PCARDBs (601).

The total deposits of all the rural cooperatives as of end-March 2017, the latest available data (there is a one-year lag in RBI’s compilation) aggregated to Rs 5.72 lakh crore and advances to Rs. 6.17 lakh crore. Their non-performing assets stood at Rs.95.1 thousand crores. The percentage of NPA range between 4.1(of State cooperative banks) to 26.6 (PACs) while those of all types of rural cooperatives put together work out to 15.41%.

Similarly, the UCBs’ deposits aggregated to Rs. 4.56 lakh crore and advances to Rs.2.80 lakh crore by the end 2018 financial year. While the goal of the cooperative, as already stated, is the welfare of its members, they are accepting the public deposits.

PMC debacle

Particularly, the depositing public has a bad experience with the Urban cooperative banks. The recent failure of the Punjab and Maharashtra Cooperative Bank led to the death of a dozen depositors who could not stand the shock of its failure.

This bank painted itself to be a top-rated bank with excellent public service providing high interest on deposits. It earned a place among the top ten UCBs of India. This UCB started in 1984 as a single branch bank in Mumbai later became a multi-state bank with 137 branches across seven States - Maharashtra, Delhi, Karnataka, Goa, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. It maintained a capital adequacy ratio of 12.62%, more than the RBI’s fixed 9%.

Read more:FADA moves SC seeking relief in sale of BS-IV vehicles after April 1 deadline

It has a high deposit base of Rs 11,617 crore and outstanding loans of Rs.8,383 as of March 2019 and earned a net profit of about Rs.100 crore for 2018-19. It has shown a low NPA, lower than the commercial banks; its Gross NPAs were only 3.67% and net NPAs (obtained after deducting the provisions set aside for bad loans from the Gross NPA) were 2.19%. Auditors gave an ‘A’ rating to this bank.

Window dressing

But all the dazzle of the PMC was a window dressing, came to the fore in the recent RBI inspection following an insider tip-off. More than 70% of the bank advances were actually NPAs. The bank has accommodated, one single group, the promoters of HDIL (Housing Development and Infrastructure Ltd) to the tune of a huge sum of Rs.4,635.62 crore. It helped the swindler through 21,049 fictitious accounts.

It is puzzling to the people as to how the UCB, regulated and supervised by the RBI (under BR Act 1949(AACS) and registered by the Central Registrar of Cooperative Societies could indulge in such a mammoth fraud drawing wool on the eyes of these two mighty institutions- the RBI and the central government? Also, the RBI ensures CAMELS norms (Capital Adequacy, Asset quality, Management, Earnings, Liquidity and Systems and controls) to protect the public interest.

As it is doing in the present case, after the PMC debacle, the RBI took strong steps after the failure of the Madhavapura Mercantile Cooperative Bank (MMC) in 2001 also. But those ‘strong’ steps were not strong enough as the PMC failure testifies. Also, the number of UCBs fell from 1,926 in 2005 to 1,551 by 2018 further signifying the frequency and magnitude of their failure.

Backdoor entry into banking

One crucial thing about the failure of UCBs shows that these banks are interested more in the deposit mobilization – a pure commercial banking function - than the welfare of their members. For instance, the fraud-hit PMC bank had 51,601 members by March 2019 whereas it has collected deposits from 16 lakh depositors who were not its members.

The UCB route provides a backdoor entry into the banking business; first, some urban primary cooperatives are farmed and later they are converted into UCBs to accept public deposits with the attraction of high-interest rates and good customer service.

The governments and RBI who regulate UCBs are unable to protect the depositors in such a way that they get back their entire money – principal amount plus interest at the contracted rate when the cooperatives go bankrupt due to the inefficiencies, frauds and other irregularities of the persons at their helms.

So, there is an urgent need for a thorough review of the functioning, licensing and controlling of the cooperatives. More importantly, they should be reoriented to confine themselves to the cooperative goals instead of the public deposits business. If they are allowed to continue with the deposits business it would be RBI’s responsibility to fully protect the depositors.

(Written by P S M Rao, Development Economist and commentator on Economic and Social Affairs)