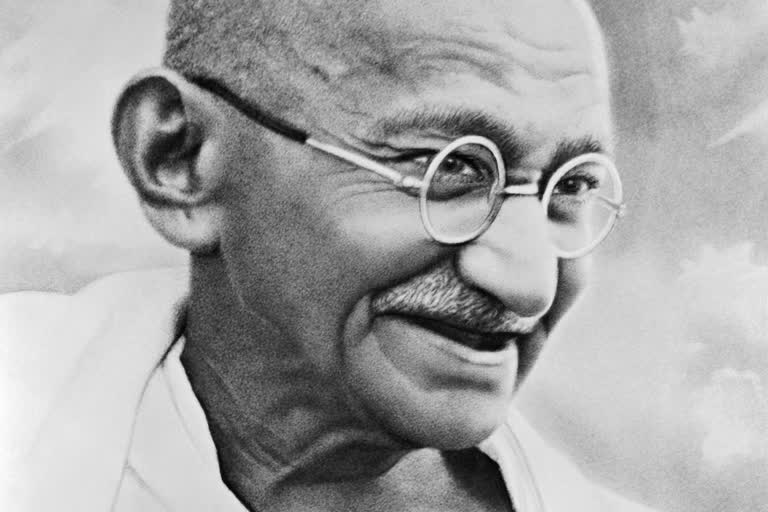

Hyderabad: Post-Independence India has witnessed a highly anglicised approach to education and other human development aspects. Mahatma Gandhi’s thoughts on education need a revisit in this context.

He had carried out some experiments in Sewagram based on his critique of western, particularly English education.

He was perhaps in a better position to suggest changes in the Indian approach to education given his first-hand experiences of Western ‘civilization’ as a whole.

Gandhi had his schooling in an ambience that did not promise evolution into the kind of a 'complete person' he had shaped into.

There has been a sea change in the society’s attitude since Gandhi enunciated his views on Post-Independence education pattern.

Even the west has begun to appreciate the Indian value system. But, how many Indians treat education as a personality development tool?

Nai Talim or New Education

Nai Talim (New Education) was popularly and correctly described as education through handicrafts.

Gandhi’s rejection of Western, particularly English, education flowed from his critique of Western civilization as a whole.

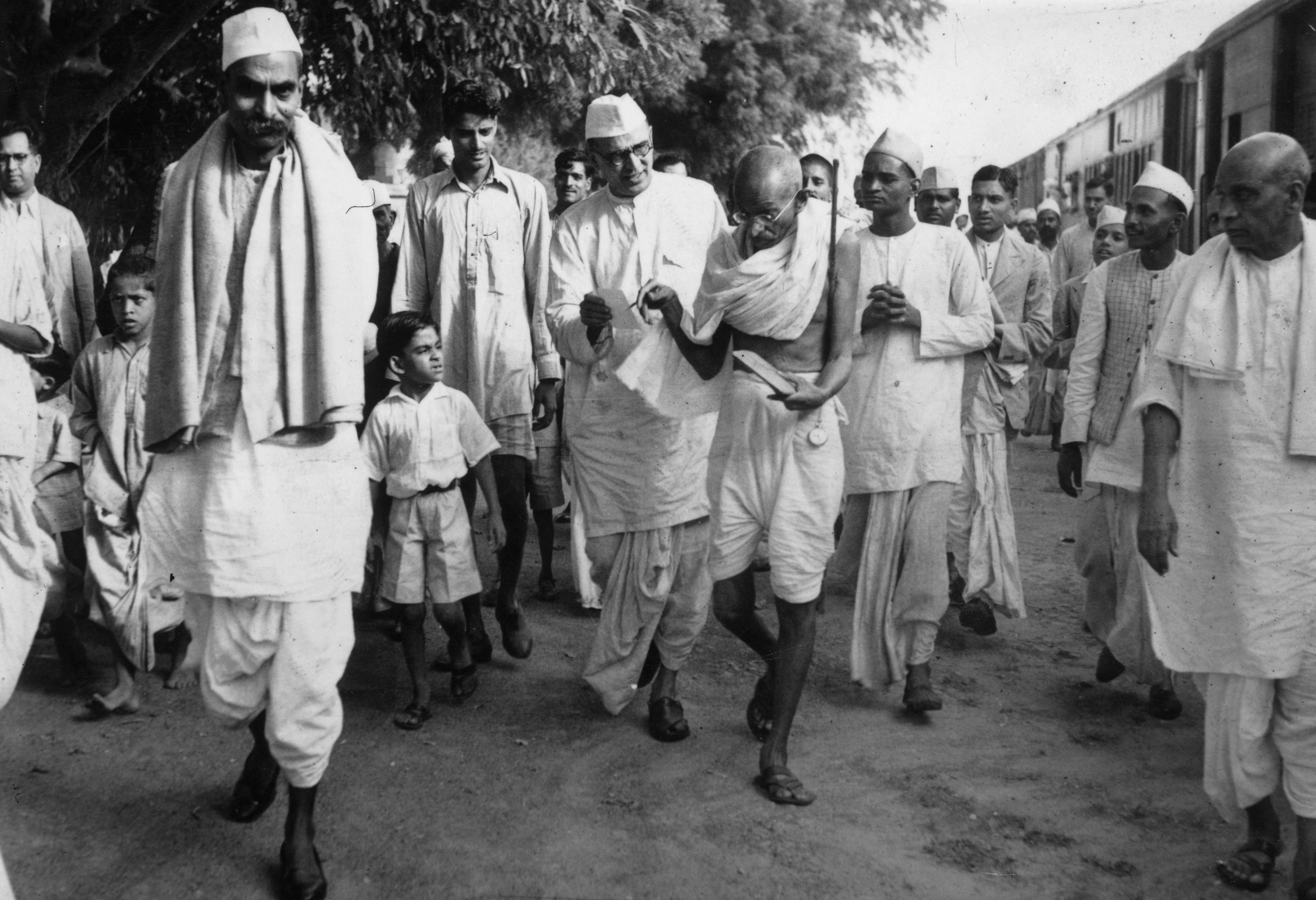

His experience in South Africa changed his outlook on politics and helped him to see the role education played in that struggle.

He was conscious of his own Western education for a number of years. But in his mid-thirties, he was so opposed to it that he wrote “the rottenness of this education’ and that ‘to give millions knowledge of English is to enslave them …” that, by receiving English education, we have enslaved the nation’.

He lamented that he had to speak of Home Rule or Independence in what was clearly a foreign tongue, that he could not practice in court in his mother tongue, that all official documents were in English as were all the best newspapers and that education was carried out in English for the chosen few.

In fact, Gandhi’s views on Industrialisation were quite contrary to those of Nehru’s. Industrialisation and the related management studies were bound to dictate the pattern of our education.

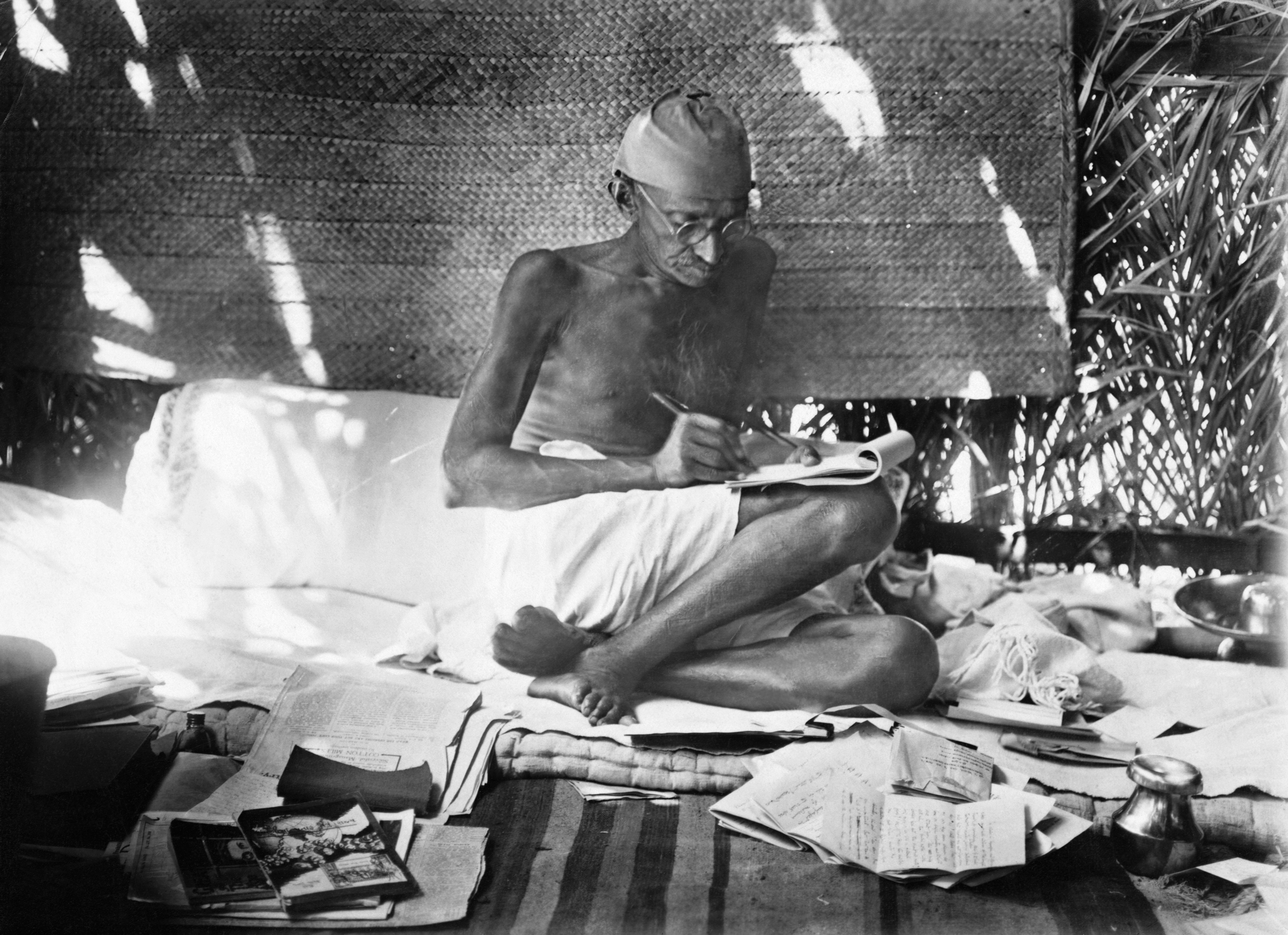

He wanted to make the learning of a craft a focal point of a teaching programme.

In a hierarchical social structure, productive handicrafts had been associated with the lowest groups.

Knowledge of the production processes involved in crafts, such as spinning, weaving, leather-work, pottery, metal-work, basket-making and book-binding, had been the monopoly of specific caste groups in the lowest stratum of the traditional social hierarchy. Those barriers are dropping down now.

His thoughts would not sound so outlandish anymore. But the Indian education system has become more and more subservient to the English language and culture.

The Wardha scheme of Education, popularly known as Nai Talim, therefore, occupies a unique place in the field of elementary education in India. This scheme was the first attempt to develop an indigenous scheme of education in the 1930s.

Gandhiji expressed his views on education through a series of articles in ‘Harijan’ on June 31, 1937.

Gandhiji views created controversies in academic circles. Finally, Gandhiji placed his views before experts for examination during the Wardha Conference on October 22 & 23, 1937.

Education Ministers of the seven states, eminent educationists, Congress leaders and workers attended the conference.

Gandhiji himself presided over it. The four resolutions passed in the conference said: 1) Free and compulsory education be provided on a nation-wide scale; 2)The medium of instruction be the mother tongue; 3) The process of education through this period should centre around some form of manual productive work suitable for the local condition and 4) The system of education will be gradually able to cover the remuneration of the teacher.

The conference then appointed a committee headed by Dr Zakir Hussain to prepare a detailed education plan and syllabus on the lines of the above resolutions.

Now it is not very difficult to realise that we have strayed very far from what Gandhi had proposed. But let us not miss out on the fact that the changes in the society have forced a rethink on English language and use of computers and machinery (even artificial intelligence) as Gandhian thought could not meet the employment needs of a large youthful population. And education has acquired a global character. But the growing joblessness still forces us to wonder if we have an education system that addresses our changing needs.

Also Read: Jabalpur, where Gandhi got a new identity but also saw his biggest defeat