In this year’s budget, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has prioritised urban development as one of the six transformative reform sectors to propel India into a higher growth trajectory. This is in conformity with the government's continued focus on building sustainable and inclusive cities.

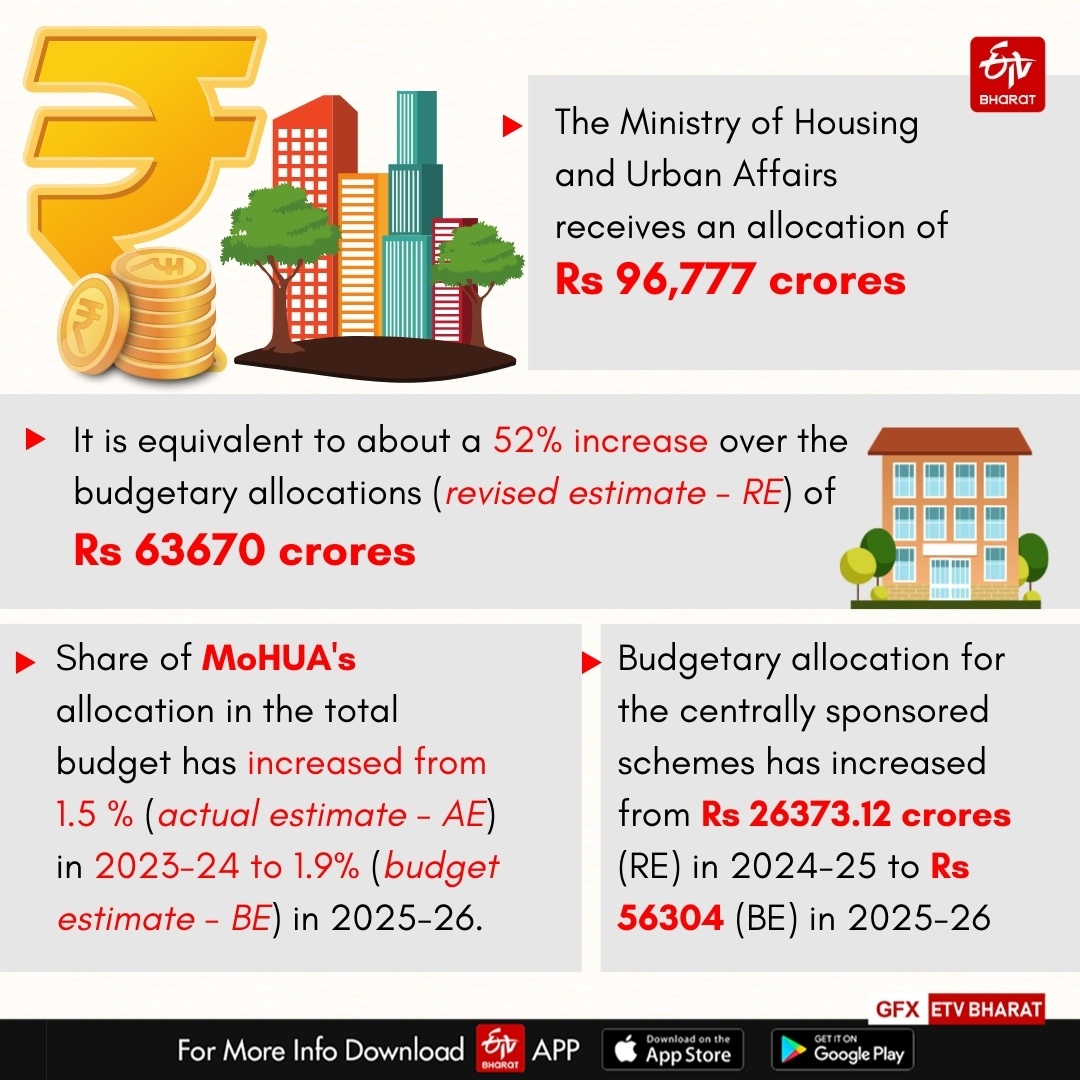

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) receives an allocation of Rs 96,777 crores which is equivalent to about 52 per cent increase over the budgetary allocations (revised estimate - RE) of Rs 63670 crores. The share of MoHUA's allocation in the total union budget has increased from 1.5 per cent (actual estimate - AE) in 2023-24 to 1.9 per cent (budget estimate - BE) in 2025-26. Cities are envisioned as the 'engines of economic growth'. Accordingly, these increasing budgetary allocations appear to be very promising. The question is to what extent they are going to be effective in addressing inequalities in access to basic amenities and infrastructure that pervade our cities.

Deconstructing The Smart Cities Mission (SCM)

The budgetary allocation for the centrally sponsored schemes has increased from Rs 26373.12 crores (RE) in 2024-25 to Rs 56304 (BE) in 2025-26. Among these schemes, the SCM has been discontinued. The SCM was introduced in 2015 to create new lighthouses of urbanisation through pan-city development aiming at the application of smart solution to existing city infrastructure and area-based development focussing on retrofitting, redevelopment and greenfield projects.

About 45 per cent of the total project costs were proposed to come from central and state/city governments while the proposed contributions from the convergence of schemes (with AMRUT, SBM, HRIDAY), PPP and loans were 21 per cent, 21 per cent and 5 per cent respectively. The Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), headed by a CEO and regulated by the Companies Act 2013, have been entrusted with the responsibility of preparing city development plans and their implementation. The implicit focus is on creating bankable urban projects and attracting private participation. The SPV-led process of city-making has bypassed the elected city government to infuse efficiency in the governance arrangements.

Yet, the prospects of inclusive urban development appear to be delusive as, on average, the Area Based Development projects account for up to 80% of the SCM funds but are benefitting only 5 to 10 per cent of the city population. In most of the cities, people from marginalised sections hardly get any chance to participate in the deliberation for preparing city development plans. Preferences towards larger and costlier infrastructure overshadow the needs of urban deprived communities. In terms of financial arrangements, as per the Standing Committee on Housing and Urban Affairs Report (2023-24), 50 smart cities could not undertake any project under the PPP model. In fact, the PPP model accounts for only 6 per cent of the costs of projects under the SCM. Similarly, only six cities could generate finds through loans for the smart city projects.

The ‘Urban Challenge Fund’ (UCF) And Emerging Concerns

In the current budget, there is a budgetary allocation of Rs 10,000 crores for setting up of an ‘Urban Challenge Fund’ (UCF) of Rs 1 lakh crore. However, the grim realities of the SCM raise serious concern as the objective and operational guidelines of the UCF and the SCM appear to be largely similar. The UCF aims to develop cities as growth hubs as well as to facilitate creative redevelopment of cities and also to implement water and sanitation projects. The fund proposes to cover a maximum of 25 per cent costs of projects that are bankable. In addition, the UCF stipulates a minimum of 50 per cent funding through loans, municipal bonds and Public-Private Partnerships (PPP).

Bankable projects emphasise on cost-recovery. City areas with better financial viability are more likely to be covered by the bankable projects and this could exacerbate the existing socio-spatial inequalities in access to basic urban services like water. Potential for leveraging municipal bond is also limited as the city governments lack creditworthiness owing to inadequate managerial and technical capacity as well as insufficient revenue mobilisation. Out of 470 cities, only 36 have obtained investment grade rating with A – and above ratings. Only a few cities for commercially viable projects would then be able to utilise the UCF allocation.

Infirm municipal health and lack of capacity makes it really difficult for the cities to attract private players and structure the PPP projects. Even in the case of SCM, private consultant-led smart-city proposals not only have turned out to be generic in nature by ignoring city-specific priorities but also have struggled to generate the required funds. As per the NITI Aayog report on reforms in urban planning capacity in India (2021), state town and country planning departments do not have one planner per city or town with 42 per cent sanctioned posts of town planners are lying vacant. Following the FM’s budget speech of 2022-23, one High-Level Committee was constituted. The committee’s report (2023) recommended setting up of a ‘National Urban Regional Planning Authority' (NURPA) as an apex advisory body to all ministries and departments on urban planning and development and allocation of resources to states over a period of five years to recruit urban planners and multi-disciplinary experts for building capacity for urban planning. The government should act on these recommendations on urgent basis to address the capacity deficits.

Under the UCF, it is also important to distinguish between million-plus urban agglomerations and other cities. Here, the recommendation of the XV Finance Commission regarding 100 per cent outcome-based funding for million-plus urban agglomerations and basic grants for other cities with specific emphasis on water supply and sanitation would be useful to account for the spatial pattern of urbanisation in India. Importantly, this year’s budget has mandated each infrastructure-related ministry to prepare a three-year pipeline of projects for implementation under the PPP mode. There is also a provision of Rs 1.5 lakh crores for 50-year interest-free loans to states for capital expenditure and reform incentives. As local governments are listed under the state list, the state governments can utilise this fund to facilitate necessary urban reforms.

Numbers Of AMRUT AND SBM (U)

Among the centrally sponsored schemes, the budgetary allocation for AMRUT has increased by 25 per cent entailing scope to improve the availability of basic services including water supply, sewerage, drainage, green spaces and non-motorised transport (NMT). There has not been any change in the budgetary allocations for the Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban). In 2024-25, AMRUT has recorded a drop of 25 per cent in revised estimate as compared to the budget estimates. The corresponding drop for SBM (U) is as high as 57 per cent. This is indicative of low utilisation of program funds that would have a regressive impact on the availability of urban services.

Positing The Urban Housing Scenario

As compared to the last budget, another flagship program - PMAY (U) including PMAY (U) 2.0 sees a cut in the budgetary allocations by about 23 per cent. The budget proposes to establish SWAMIH 2 (Special Window for Affordable & Mid-income housing) fund of Rs 15000 crores aiming at completion of stalled housing projects and to scale up the supply of affordable housing. However, this fund appears to be a case of misplaced priority as the housing market in recent times has experienced increase in housing sales, especially of premium homes, upward movement of housing prices and renewed interests of the institutional investors to back the residential projects.

In our cities, housing affordability remains a key issue for the MIG and LIG/EWS households. As per the RBI residential asset price monitoring survey across 13 cities (2019), the house price to income ratio is 61.5 implying that the median housing price is covered by 61.5 times of the median monthly household income. The UN-Habitat considers housing expenditures exceeding 30 per cent of the monthly income as unaffordable. Budgetary allocations of Rs 2500 crores and Rs 1000 crores under the interest subsidy scheme component of PMAY(U) 2.0 for EWS/LIG and MIG categories could potentially improve their affordability. In addition, there is an allocation of Rs 2500 crores to provide housing for industrial workers. In spite of these budgetary provisions, about 50 per cent reduction in the RE for PMAY (U) in 2024-25 would perturb the dream of ‘Housing for All’. So, the focus should be on efficient and faster utilisation of PMAY (U) funds to facilitate low-income households’ access to affordable housing.

Issues With Urban transport

The MRTS and metro projects account for about 36 per cent of the total MoHUA budget allocation with an increase of 40 per cent over the last year’s budgeted estimates. In practice, metro projects have failed to address the problem of urban mobility in most of the Indian cities. The ridership in cities like Mumbai and Bengaluru are 30 per cent and 6 per cent of their potential capacities respectively. People have shown little interest in availing metro services due to poor last-mile connectivity and long waiting times between two trains. Unplanned expansion of metro networks is not suitable to reach the minimum network threshold necessary for increasing ridership. Equally concerning is the marginal increase in budgetary allocation from Rs 1300 crores for 2024-25 to Rs 1310 crores in 2025-26 under the PM e Bus Sewa Scheme. The focus should have been on improving the city bus services and NMT to better peoples’ mobility.

Dealing with Data Inadequacy

Any good policies need accurate data. National Urban Digital Mission (NUDM) was launched in 2021 to synchronize urban-centric data platforms for city performance monitoring, dissemination of data and capacity-building training for city officials. For 2025-26, NUDM receives a budgetary allocation of Rs 1250 crores. However, the revised estimate in the current financial year is significantly low at Rs 108.7 crores against the allocated amount of Rs 1150 crores. This would jeopardise the process of digitalisation of municipal services and institutionalisation of citizen-centric urban governance and service delivery across the country.

Moreover, census data form the basis for many significant decisions related to the provisioning of basic urban services. For example, as per the AMRUT guidelines, decisions related to the establishment of water and sewerage lines throughout the city are based on Census data. The Budget 2025-26 has allocated Rs 574.80 crore for Census related works. This allocation is significantly lower than the budgetary allocation of Rs 3,768 crores in 2021-22. This is indicative of further delay in the decadal census exercises. The absence of updated demographic and socio-economic data can deprive the people especially the poorer sections of their access to urban services. The collection of census data needs to be reprioritised to effectively plan for cities that are becoming increasingly unequal.

(Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer. The facts and opinions expressed here do not reflect the views of ETV Bharat)