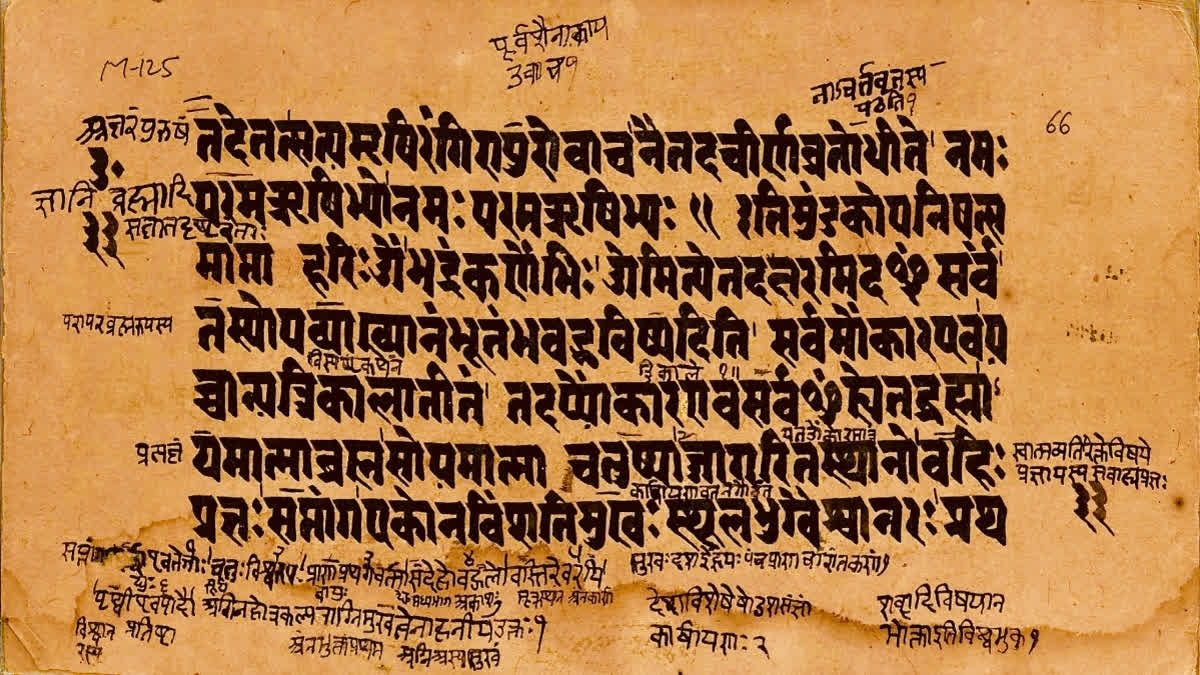

The Upanishads are said to have been written, tentatively, between the 8th and 1st century BC (with some said to have been written later). It is ironical that such ancient texts could come to cast their footprints on modern-day science. It is widely believed, and not wrongly so, that the revolutionary minds that paved the way for the twentieth century theories in quantum mechanics came to be influenced by the wisdom of the Upanishads — also known as Vedanta, or the 'cutting edge' of the Vedas (to cite the philosopher, Professor Arindam Chakrabarti). The uncanny behaviour of subatomic particles and the potential uncertainties that they found in their actions — as if the particles themselves appeared to exhibit subjective behaviour — led quite a few of them to seek theoretical alliances with the Upanishads.

Atman=Brahman?

Naturally, the alliance between Vedantic philosophy and quantum mechanics has been seen with suspicion by scientists, secularists, and even people of religion. This is partly because the Upanishads can seem esoteric and obscure, especially to superficially conditioned minds. But a larger reason for the suspicion is that the Upanishads also contain the seeds of radical dissent against all forms of social rigidity, divisive identitarian politics, inequitable hierarchies, and traditionally sanctioned injustices that, oftentimes, carry on even in the name of religion and religious freedom.

In the Vedic tradition, the Upanishads are grouped under Jnana Kanda (or wisdom chapters). They are distinct from the Karma Kanda (or duty chapters) and Upasana Kanda (or ritual chapters). Instead of codes and prescriptions regarding duties and rituals, the Upanishads contain wisdom about the fundamental realities of nature, phenomenology, self, and the cosmos. In a nutshell, they contain the secret to unite the Brahman (universal soul or consciousness) with the Atman (individual spirit).

In the modern era, the wisdom of the Upanishads reached Europe during, or a little after, the Renaissance. It is sometimes claimed that Persian translations of the Upanishads commissioned by Dara Shikoh (eldest son of emperor Shah Jahan) began being translated in seventeenth-century Europe. One of the key figures in the quantum revolution, Erwin Schrödinger, is said to have been introduced to Upanishadic philosophy in 1918, through the works of the early nineteenth-century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer.

Schopenhauer believed the Upanishads to be the most 'elevating' object of study in the world, and he acknowledged them to be 'the solace' of his life and death. Schrödinger, meanwhile, is said to have named his dog Atman, and, as the legend goes, he used to jocularly call the equation 'Atman=Brahman' as the second Schrödinger’s equation (the first one being his Nobel-prize-winning equation on the wave function of quantum mechanical systems). Around the same time, English poet, Thomas Stearns Eliot, published an essay by W.B. Yeats in the Criterion (1935) on the Mandukya Upanishad — to which we shall return towards the end of this article.

Enter Mandukya Upanishad

While the history of intellectual intersections between Upanishadic philosophy and quantum mechanics is deeply interesting, it is perhaps well-known now to most enthusiasts of either discipline. But the nuances of Upanishadic philosophy are yet to be wholly disseminated. One can find a reading of the Mandukya Upanishad deeply fulfilling, in this regard. Containing only twelve slokas or verses, and despite being the shortest of the Upanishads, the Mandukya is a powerhouse of contemporary ideas about states of the mind and consciousness.

In fact, the Muktita Upanishad, containing dialogues between Lord Ram and Hanuman, when the latter asks the former about the path to salvation, the former recommends a thorough examination of Mandukya Upanishad, alone, for the attainment of Kaivalya or Moksha. If, perchance, such an examination does not help in god-realisation or salvation, Lord Ram recommended studying 10, or 32, or the entire canon of 108 Upanishads.

It is held that Mandukya Upanishad was written around 100-200 AD. Accordingly, academic historians have attempted to trace resemblances between Mahayana Buddhist philosophy, especially the concept of sunyata, and the principal tenets of the Mandukya. However, some scholars, including Ramchandra Dattatreya Ranade and Stephen Phillips have dated its authorship as far back as around 500 BC. The Mandukya Upanishad is today considered almost incomplete without the Mandukya Karika—the critical commentary—authored by Gaudapadacharya, the grand-teacher of Adi Shankaracharya. The karika is also held to be one of the oldest existing intellectual foundations of the Advaita (monist or nondual) Vedanta school of Vedic and Vedantic philosophy.

Later, Madhvacharya, a thirteenth-century proponent of dualistic Vedanta philosophy, sought to study the Mandukya Upanishad as a theistic doctrine meant to be interpreted through the principles of Vaishnava-oriented bhakti yoga. In recent times, Swami Sarvapriyananda, a senior monk and philosopher of the Ramakrishna order (among other exponents from other illustrious orders) has played a yeoman’s role in popularising the Mandukya.

Mandukya for Mind Sciences

While it may seem like a far-fetched claim, the Mandukya Upanishad continues to directly or indirectly influence contemporary theories of mind sciences and psychology. Included by John G. Howells in the World History of Psychiatry (1975) as an 'exposition of different states of consciousness', the discussions on the Mandukya have featured in prestigious refereed journals like the Psychiatric Quarterly, Indian Journal of Psychiatry, Frontiers in Psychology, Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, and the NIMHANS Journal, to name only a few.

To knowers of Mandukya, these inclusions will not seem surprising, at all. The Mandukya Upanishad categorises cognitions of reality in three states of consciousness — waking (jagrat), dreaming (svapna), and deep sleep (suṣhupti)—with consciousness itself being the fourth state (chaturtha), or Turiya, the one and the unchanging. Often, the example of a cinema theatre screen is offered as an analogy to consciousness, on which the drama of human social and private lives is played and cognised like a film.

The waking state produces cognition, perception, and knowledge in the sthula or gross body. The dreaming state produces perception, cognition, or knowledge in the sukshma or subtle body. The state of deep sleep, also known as the kāraṇa or causal body, is the state where perceptions of waking and dreaming are contained in dormancy or seed-states. 'Turiya', that transcends these three states, is the signifier of the practically indescribable phenomenon that transcends both saguna (personified or embodied) and nirguna (impersonal or formless) classifications of Brahman. This state is essentially tantamount to a pure condition of wisdom without desire and suffering, or what is also known as sat-chit-ananda (existence-consciousness-bliss).

The tenets of the Mandukya are often linked to Sankaracharya’s famous and ostensibly sweeping dictum: 'Brahma satya, jagat mithya' (‘Brahman alone is real, all else is illusory'). Restated in a secular phraseology, this essentially distils down to the Shakespearean mantra from his play As You Like It: 'All the world’s a stage,/ And all the men and women merely players.'

In the words of the doyen of psychiatry, the late Dr. A. Venkoba Rao: the restorative or re-equilibratory functioning of dreaming is implied in the Upanishadic aphorism: “He who desires dreams; he who does not desire does not dream.” This means that the seemingly real world of waking and the seemingly false world of dreaming, induced by desire, are manifestations of the causal self (the state of deep sleep), and the binary between reality and falsehood itself evanesces in comparison to consciousness — or the stage of the sovereign playwright, as it were.

Obviously, seen in empirical terms, this is virtually an unrealisable principle. Nevertheless, in various theoretical combinations — inspired by the Mandukya, or its latter-day religious, secular, and scientific exponents — the mantra has helped many people overcome traumas, griefs, psychopathological traits, addictions, anxieties, guilt complexes, and so on, and alchemize their states of suffering into individually, socially, and perhaps even spiritually rewarding states of consciousness.

Is this True or was That True?

The fundamental principle of the Mandukya may appear easy to grasp, understand, or even dismiss — as the case may be. In fact, a hasty interpretation of the Upanishad can even cause delusions of enlightenment and hallucinatory egotistical perceptions of oneself. Lest the Upanishad be not misunderstood, one of the legends told by some teachers is as follows.

Once, the legendary emperor of Videha, King Janaka — also the father of Sita — is said to have had a terrible dream, wherein he was brutally defeated in battle and was rendered homeless, penniless, and emaciated, without his family. The traumatised emperor roamed from village to village in search of food, and upon finding a bowl of gruel at a gathering of peasants, his tired body dropped insensate.

As he woke up, he sat aghast, thoroughly shaken by the experience. Hours passed, as his wife and courtiers attempted to cajole the emperor out of his shock and stupor, while he kept muttering: is this true or was that true? Meanwhile, the Vedic sage, Ashtavakra, also credited as the author of the Ashtavakra Gita, happened to be passing by the capital. When the courtiers brought him to see the mentally paralyzed emperor, the emperor asked Ashtavakra, as well: is this true or was that true? As Ashtavakra examined Janaka's state, the sage asked the emperor if all this (the king’s family, the court, the kingdom, the affluence, and so on) existed in his dream. The emperor answered in the negative. Following this, Ashtavakra asked whether all that (the battlefield, the days of pennilessness, destitution, hunger, and trauma that the emperor experienced in his dream) existed in his waking state. Again, the emperor answered in the negative. 'Therefore, emperor,' remarked Ashtavakra, 'neither is this true nor was that true. Only you are the truth.'

Ashtavakra’s message appears to be that we are only as true and none the truer than what is ultimately our consciousness — singular and collective at once. That is, experiences of perceptions of reality produced during our waking states are not necessarily always less false or unreliable than dream experiences. This can be broadened to glean a larger worldview, especially in relation to Yeats' interpretation of the Mandukya Upanishad.

To experience an unchanging and untarnished perception of the unchanging reality — whether as a deified God in the Himalayas or as the formless universal Brahman — one need not obey the mandate of crossing the boundaries of one's nation and seek divinity in foreign lands. To extrapolate from this message further, claiming the profound tenets of the Mandukya Upanishad or the Upanishads, in general, or the Vedas at large, as typical of a fixed national identity or cultural monopoly is one of the most certain ways to lose one's grasp over reality itself, let alone finding the key to sacred experiences. Doubtless, the Upanishads were India's gift to the world, and they will remain as such. And, doubtless, the theories of quantum mechanics have found meaningful resonances with Vedantic concepts and allegories. But like Janaka’s imperial states of dreaming and wakefulness, both are, after all, temporal and ephemeral experiences. The deeper lesson of the Mandukya and the Upanishads is to look far beyond the horizons of such short and illusory goals.

At least, that is what Lord Ram intended for his most favourite devotee, Hanuman, if not for all of us.