Ever since the Modi government came to power, it has been stressing on natural farming in one way or another. Starting with a program of Paramparaghat Krishi Vikas Mission to emphasise on zero budget farming or awarding various central government awards to indigenous seed savers and farmers, the government is trying to encourage natural farming in the public view.

The government even has allocated a yearly budget for natural farming. This clearly shows their intent. But the question remains - is political will enough to bring an organic farming revolution in India? Perhaps not, because a lot is needed.

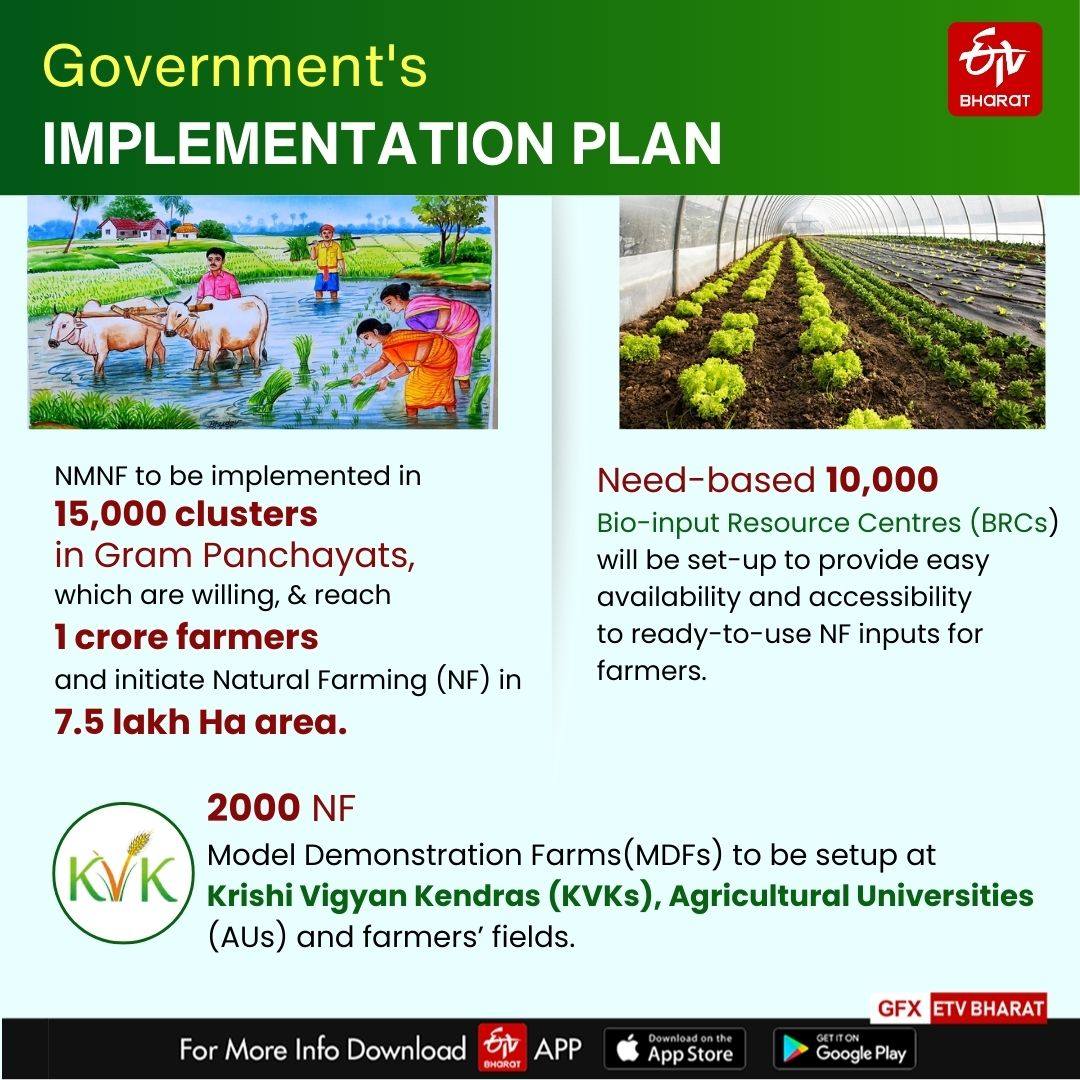

Recently the government announced about Rs 2481 crore for the promotion of natural farming along with other measures like the creation of 2000 demonstration farmers, farmers training and set a target of reaching one crore farmers and initiating Natural Farming (NF) in 7.5 lakh Ha area. But a big question: who is responsible for training and creating this organic/natural farming infrastructure? Is it going to be incumbent agricultural scientists, extension officers or farmers themselves? There is no clear answer.

First, let us look at the history of “modern agriculture” which is synonymous with the “Green Revolution”. It was during the late 60s that agricultural chemicals and new industrial seeds started to enter the Indian fields. Much of this research and technology was financed by the US government and after Lal Bhadhur Shashtri's untimely death was part of an agrarian re-structuring that India was forced to undergo.

The government faced an uphill task of trying to convince farmers to shift from organic cultivation to adopt foreign seeds, fertilisers and agri-chemicals. Farmers in Punjab rejected the seeds for almost a decade. It took a solid two decades for the government to almost forcefully achieve a mass-scale adoption of the Green Revolution. Still, many of Punjab’s elder generation of farmers will recount how extension officers did fly-by-night operations and threw fertilisers and seeds in their fields.

Since that period, Indian agrarian institutions and research have dropped indigenous agrarian practices and worked solely on the tenets of American-style industrial agriculture. Most Indian agri-scientists often have a disdain for traditional agriculture and a vast majority of them are not trained in it either. Only a small percentage of them have basic knowledge of traditional agrarian practices and it would take years before we can build a strong knowledge pool related to organic agriculture covering areas of pest management, soil fertility, natural-based planting, etc.

Our agrarian diversity matched with 16 plus agro-climatic zones makes it very hard to have one set of agrarian practices. Each region has their own way of farming and organic or natural farming is based on the agri-climatic zones, the one-size-fits-all all model of industrial agriculture where chemical fertilisers and pesticides rule the roost, don’t fit for organic agriculture.

So what is needed to relearn the wisdom of our ancestors? The first thing the government needs to do is create a demand. APEDA, NAFED and FCI should all have a special cluster-based program for procuring organic produce. This program should have pre-sowing price floors, so farmers can actually plan and sow crops. They can then register with various programs from organic crop procurement. Once the registration is done, APEDA, et al can have a monitoring role through the NPOP system or through a PGS system. With a pre-sowing MSP for organic rice or legumes or even oilseeds, the government can in a short duration create a huge shift.

Local procurement centres linked to the proposed organic bazaars and haats in cities can boost local economies.

The second big demand is that the government needs to create new public sector jobs by creating natural farming departments in each district for promotion of organic nature for a minimum of 15 years. This should be done at par with the "green revolution" steam. The role of new natural farming departments would develop organic farming strategies for each district with special attention to various blocks and gram panchayats.

Farmers, FPOs, other farmers co-operatives, et al should sit with chart out plans with agro-scientists and state agricultural institutions on how to grow in accordance with agro-climate, water sustainability and market demand. Through this way, we can effectively and rapidly increase organic clusters in the country, while also making organic produce reasonable and in the reach of the common person.

But if all the scientists are trained in ways of industrial agriculture, where will we find people to work at the natural farming departments? The answer lies in creating a new syllabus and research departments in agricultural universities in the country. All agricultural universities should have courses in organic agriculture. IARI and ICARs can take a lead role in this. The government needs to also create flagship universities or steer the mandate of a few of the existing agricultural universities towards natural farming. Once the government gives a push, many students will be drawn towards it.

We need to dedicate a special budget to archive and research on India’s indigenous agrarian and animal husbandry wisdom. By reviving Vriskhayurveda (Tree ayurveda), animal ayurveda and agrarian techniques, we can make them stand the litmus test of modernity and help improve them where necessary because each time we don’t have to reinvent the wheel, we only have to learn from the wisdom of our ancestors.

This step will also increase our traditional knowledge and help archive it, but it also has the added benefit of presenting newer solutions to diseases, integrated pest management, soil rejuvenation, etc. Through some of these steps, the government can fill gaps, and take India forward to fulfil her natural farming revolution.

(Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer. The facts and opinions expressed here do not reflect the views of ETV Bharat)