There is a discernible gap between India’s urban governance policy rhetoric and its ground realities. Indian cities aspire to become 'world-class', albeit, they lack empowered administrative machinery to plan for urban development. This is in clear contrast to the experiences of international metros run by the mayor with clear decision-making power over the functions and finances of the city governments.

Attendant institutional arrangements make the city administrators accountable to its citizens, thereby making cities inclusive and vibrant. Recently published Urban Governance Index (UGI) 2024 by PRAJA Foundation has indicated crippled city administration in India. On a 30-point scale under the sub-theme of "Empowered City Elected Representative and Legislative Structure", the state-wise scores (excluding Meghalaya and Nagaland) ranged from 6.79 for Punjab to 18.63 for Kerala.

India has witnessed demonstrable policy attention for city empowerment, which began with the enactment of the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act (CAA) and subsequently wedded as reform conditonalities for accessing funds under the major urban development programs. Yet, as the UGI suggests, Indian cities are in many ways disempowered to decide and implement comprehensive plans.

Irregular Municipal Elections

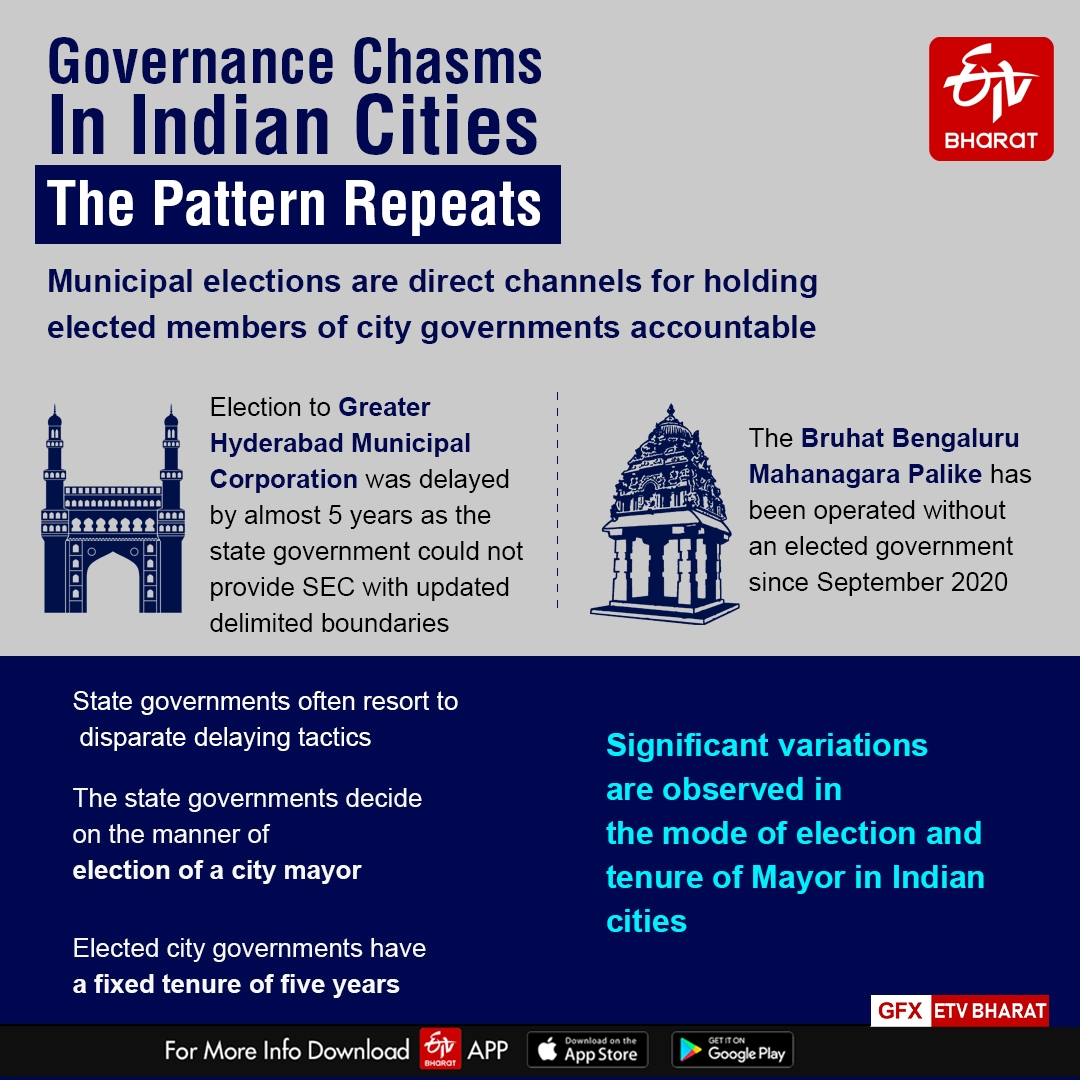

Municipal elections are the direct channels for holding the elected members of the city governments accountable. The 74th CAA mandates direct election mandatory for filling up of all seats in the city governments with a term of five years. The State Election Commission (SEC) is entrusted with the task of supervising municipal elections that involve three critical processes - preparation and updating of the electoral rolls, delimitation and preparation of the reservation roster and the conduct of the election.

In practice, these tasks are managed by multiple institutions, resulting in inordinate delays in municipal elections. The SECs in only four states have been entrusted with the responsibilities of conducting delimitation of wards while in other states this exercise lies at the discretion of the state governments.

The election to the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) was delayed by almost five years because the state government could not provide the SEC with updated delimited boundaries and the reservation rosters. Preparation of reservations rosters is complex as well as opaque often leading to litigations.

In many cases, apart from reserving the wards for women or mayor's position, reservation is required for SCs and STs within women reservation. In Karnataka, between August 2018 and January 2020, 187 out of 280 ULBs could not form the municipal council due to court cases on government mandated rotation of reservations for the post of Mayor and Deputy Mayor.

The Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike has been operating without an elected city government since September 2020. This is attributed to the successive state government's unwillingness to hold municipal election in the pretext of introducing the new BBMP Act in 2020 and the Greater Bengaluru Governance Bill in 2023 for governing the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP).

In general, the state governments often resort to disparate delaying tactics as the state-level politicians and bureaucrats see elected city councilors as direct threat to their own influence and constituency and consequent erosion of the domain and authority of the state governments.

The city governments are left at the mercy of the state governments that may dissolve the formers for any purpose. This is unwarranted, even petulant. Such irregularities in municipal elections and consequent absence of elected municipal councils weaken the scope of democratic decision-making and accountability as envisaged in the 74th CAA.

The Mayor – Ceremonial Head

Following the 74th CAA, the state governments decide on the manner of election of the city mayor. Although the elected city governments have a fixed tenure of five years, significant variations are being observed in mode of elections and tenure of the Mayor in our cities. There are provisions for both direct and indirect model of elections with the tenure varying from one to five years.

Even, in some states the mode of elections varies with change in political party in power at the state level. Cities like Mumbai, Pune, Surat and Ahmedabad have mayoral tenure of two and half years. In contrast, some of the large cities like Bengaluru and Delhi have mayoral tenure of only one year. Given the possibilities of changing priorities of the leaderships, such short tenurial terms rarely offer any opportunities for facilitating any kind of transformative urban policy reforms.

Moreover, there is a complete lack of clarity on the role and functions of the mayor creating serious governance deficits. Elected councillors lack the technical expertise and skills necessary to run and manage a city government. As per the UGI 2024 report, no state has provisions for regular training for elected councillors.

Fragmented governance

Typically the state governments appoint administrators to run the city. This has almost become a routine statutory exercise of the state governments. The state-appointed Municipal Commissioner enjoys executive authority over municipal issues. However, the elected city governments do not have much authority over the functioning of the Municipal Commissioners.

To make matters worse, the elected city governments are unable to get the basic urban service-related issues fixed as most of these are under the purview of state-controlled parastatal bodies that are not accountable to the city governments. City plans are not prepared by the elected city governments. State development authorities or international consultants do planning for the cities.

There are, however, some exceptions. The commissioner in Kolkata, being the chief administrative head, functions under the supervision and control of the mayor-in-council (MIC). Bhopal also has the MIC system with a directly elected mayor enjoying the financial power of sanctioning projects upto Rs five crores. In Kerala, the Mayor enjoys the authority to annually evaluate the performance of the Commissioner.

Some state governments (e.g., Gujarat, Karnataka) provide for a Standing Committee empowered to take decisions on municipal issues. However, not all the state governments devolve authority to the city mayor for appointment of the chairpersons of these committees. As per the UGI 2024 report, even in as many as 15 out of 31 cities, the mayor is not the chairperson of the Standing Committees.

The Standing Committee Chairman is more powerful than the elected city Mayor. Elected councillors could hardly influence decisions taken by the committees. This has two important implications for urban governance. First, the accountability of the city government is weakened as the administrators are not accountable to the people. Second, the existence of multiple decision-making centres entails fragmentation of political authority at the city level.

Nevertheless, given the capacity constraints at the city level, it is pragmatic to take help from the state-parastatals and urban experts. But that should not lead to the marginalization of the city governments and their elected councillors, as is now the case. Equally important here is to identify the functions for which cities are solely responsible. In case of functions to be shared with state agencies, a clear-cut division and synchronisation of planning and implementation is required.

The Way Forward

Indian cities dream of becoming world-class is untenable as long as they have such persistent governance chasms. So, reforms are needed to allow the cities to decide on their development trajectories. This needs to be complemented with a slew of other measures including regular municipal elections and capacity building of the elected representatives that are critical for establishing empowered city governments in India.

(Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer. The facts and opinions expressed here do not reflect the views of ETV Bharat)