India is urbanizing at a fast pace with its cities most vulnerable to climate change. Proliferations of diverse economic activities and increasing demand for urban infrastructure have serious environmental implications, e.g., in terms of their ecological footprint and greenhouse gas emissions.

Changes in urban landscapes coupled with high population density pose threats of accumulation of heat and increase in anthropogenic activity that affect crucial climate parameters like rainfall and pollution. In recent times, the incidences of heat waves, floods, variations in precipitation and water stress have become more frequent in urban India. There has been a deterioration in public health and a greater chance of the spread of diseases due to overcrowded and cramped living conditions.

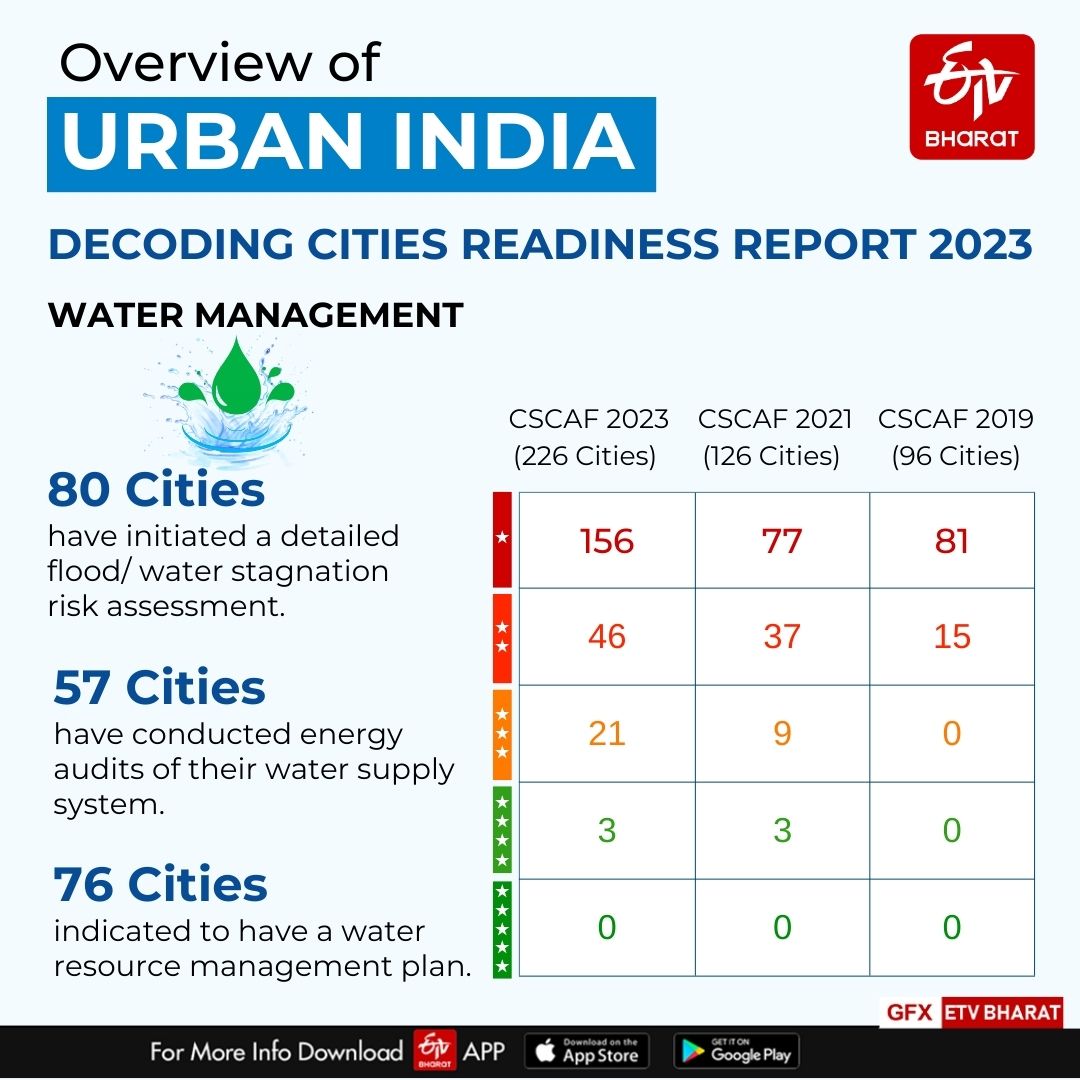

As per the Cities Readiness Report 2023, 21 major Indian cities including Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai and Hyderabad are heading towards zero groundwater levels, affecting access for 100 million people; 18 Smart Cities and 124 AMRUT Cities are prone to high-risk of flooding.

Existing problems of inadequate provision of urban basic services including housing, pollution and depletion of natural resources have compounded the impacts of climate change. Urban poor living in informal settlements are hit hard by climate change-induced shocks in conjunction with their limited access to essential urban services.

Moreover, women are more vulnerable to climate extremes because of their gendered role – e.g., they often need to queue at water taps or tanks for long to fetch water for their households. Climate change events also impact the livelihood opportunities of the poor that are subjected to climate cycles. Further, there are large variations in the nature of climate risks faced by the cities depending on their local geography and climatic characteristics. Following such differential impacts across different groups of people as well as among the cities, the urgency of tailor-made climate policies cannot be overstated.

Outlining the Climate Responses

In India, the National Action Plan for Climate Change (NAPCC) is implemented through eight missions aiming to balance efficient as well as innovative climate actions with the nation’s development challenges related to an increase in economic growth and reduction in poverty.

At the state level, many state governments have prepared the State Action Plan for Climate Change (SAPCC) to negotiate with the contributors to and consequences of climate change. However, in their attempts to align with the NAPCC, these SAPCCs have overlooked the regional variations in climate factors and could not produce the desired benefits.

At the city level, urban local governments have no mandate to prepare any action plans on climate change. This is in contrast to the provisions in many European countries. For example, in the United Kingdom, local planning authorities and city governments are mandated to produce local planning documents focusing on mitigation and adaptation to climate change.

India’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) pledge to facilitate sustainable urban development through measures like the provision of urban basic services, access to clean energy, electric mobility and so on – all of which entail climate mitigation and adaptation co-benefits.

Of late, the city governments have attempted to manage climate change issues through their development plans. The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) has prepared the Mumbai Climate Action Plan 2022 to identify the city’s vulnerabilities (e.g., in terms of urban flooding, urban heat, air pollution etc.) and strategize plans to address them. The plan also provides for a ‘Climate Cell’ to coordinate the plan implementations.

In India, city governments’ roles are primarily limited to the implementation of various central and state schemes for the provision of urban infrastructure and services. There are target-oriented schemes –e.g, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Urban) for the provision of 1.12 crore houses in cities; Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban) to make the cities garbage-free – with deep implications for climate mitigations or adaptations.

Attempts have been made to integrate the local climate concerns in the implementation of some of these schemes. In Rajkot, adaptation measures like rainwater harvesting and ventilation are attached to the construction of houses under the PMAY(U) scheme. Some city plans emphasize the improvement of centralized water and sanitation networks or the provision of better solid waste management while others plan for relocation of informal settlements or the development of disaster warning systems.

The state-level parastatals and state governments’ departments working in the areas of environment and disaster management play crucial roles in the formulation of city-level climate action plans. International and national non-state actors focused on climate change issues, also provide technical support to the city governments’ climate responses. Moreover, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) has introduced Climate Smart Cities Assessment Frameworks to ensure consistency of city climate action plans to national priorities. The Ministry has also supported the establishment of the Climate Centre for Cities (C-Cube) at the National Institute of Urban Affairs to provide advisory and technical support to prepare city-based climate action plans. The Centre liaisons with international platforms, e.g., the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy (GCoM) and the European Union (EU) to plan city-specific climate solutions.

Understanding the Challenges

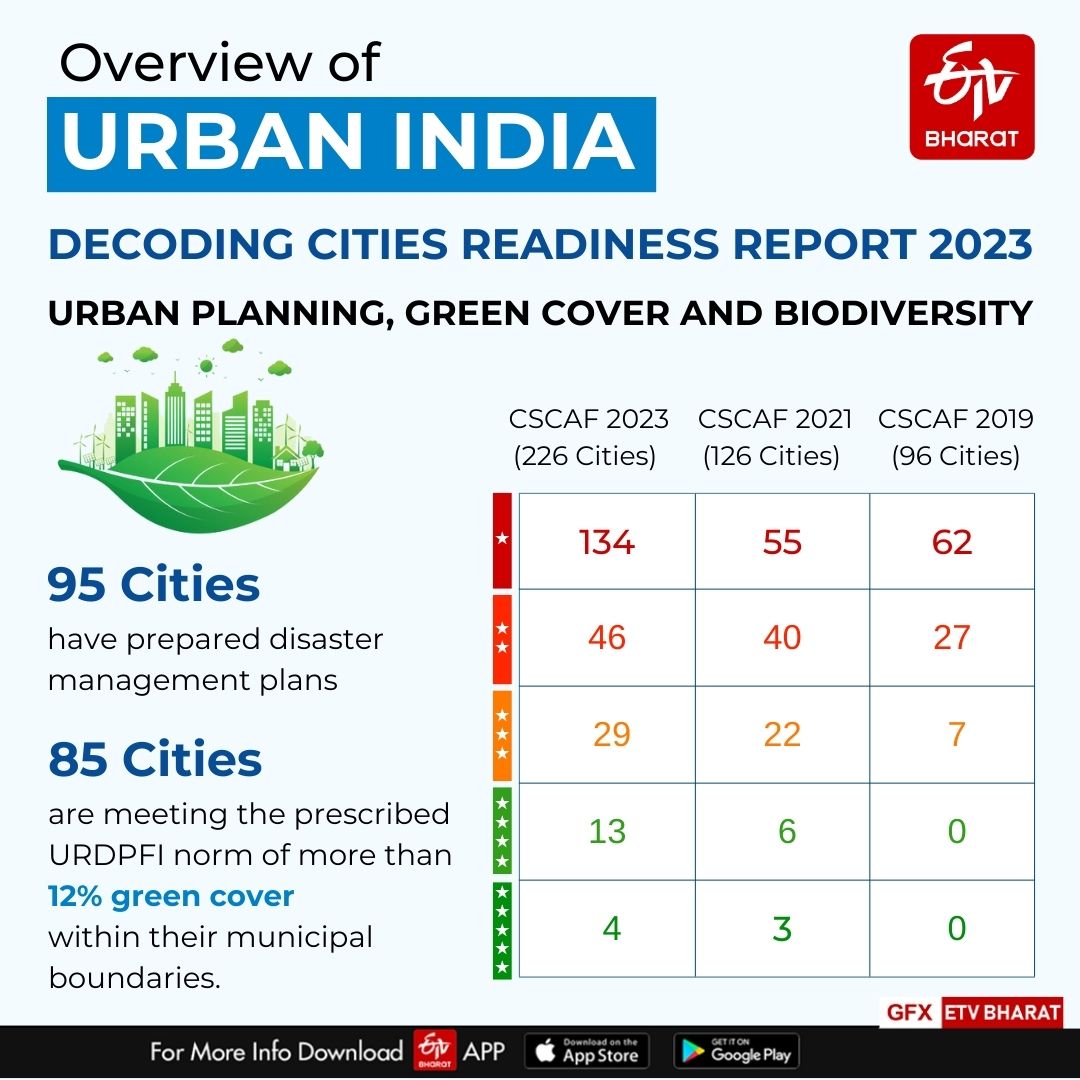

However, the approaches and contents of climate action plans raise some concerns. First, disparate climate risks in Indian cities are strongly interlinked and thus require a coordinated approach across the sectors. Multiple entities operate at the city level to plan and manage urban services but with little coordination among them. This, in turn, increases the scope for fragmented and inconsistent efforts in addressing climate issues. There is evidence of climate action plans having little or even conflicting impacts on developmental practices in Indian cities. For example, Guwahati Master Plan 2045 allows high-density commercial development along the Bhalaru river and this would only intensify the flood risks and consequent worsening of livelihood opportunities of the affected people.

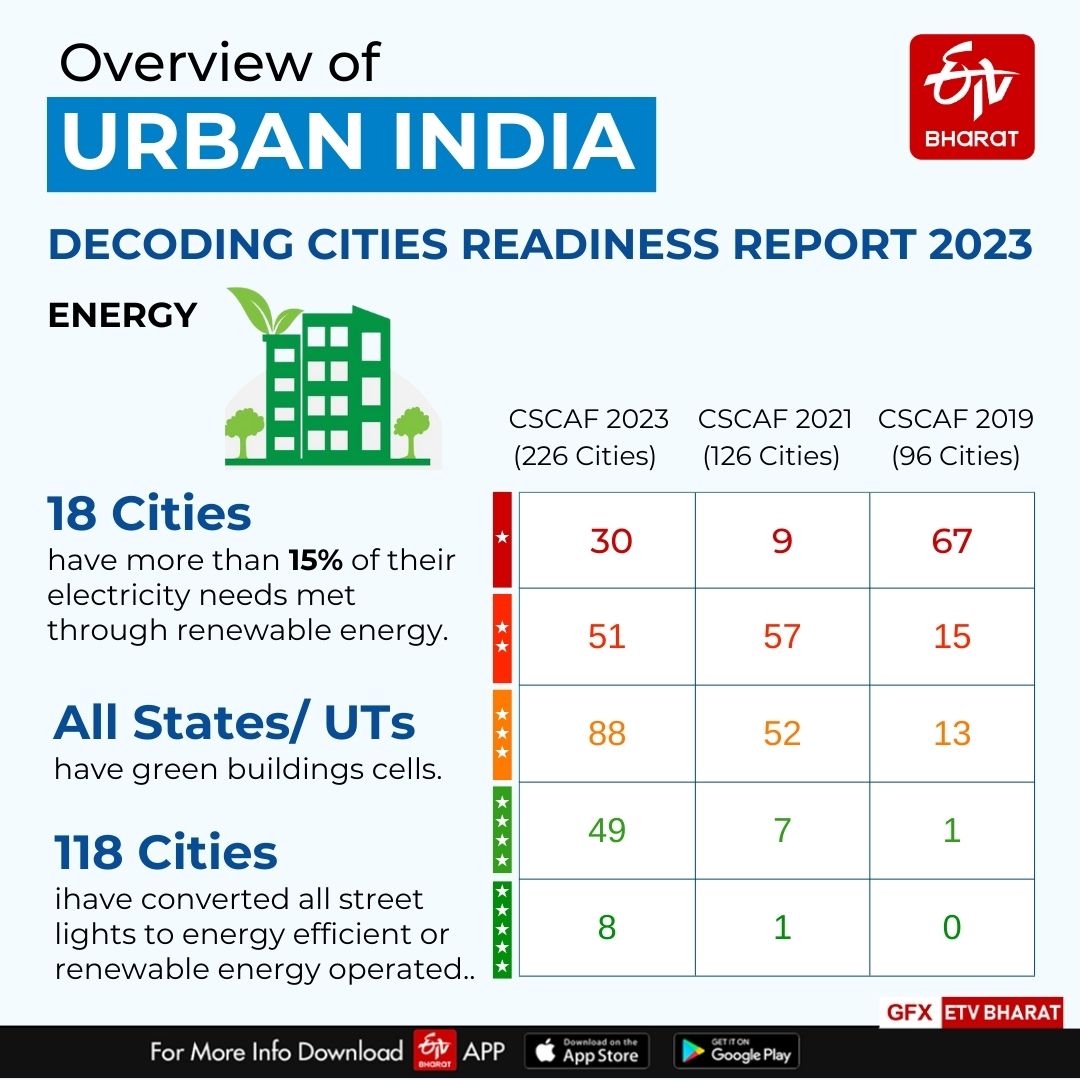

Second, climate responses of the cities appear to be too techno-centric with a focus on solutions like improving centralized water networks, energy audit of the water supply system, scientific management of solid waste, slum clearance, conserving public spaces, air quality monitoring stations, enforcement of roof cooling and so on. While these are crucial, the needs and priorities of marginalized people including women have received less attention. Significant proportions of them do not have access to water, waste management and shelter. So, any action plan should not only neutralize climate-specific risks but also address the current deficits. Hardly any attempts have been made to facilitate community engagement or to leverage local knowledge in the preparation of climate plans.

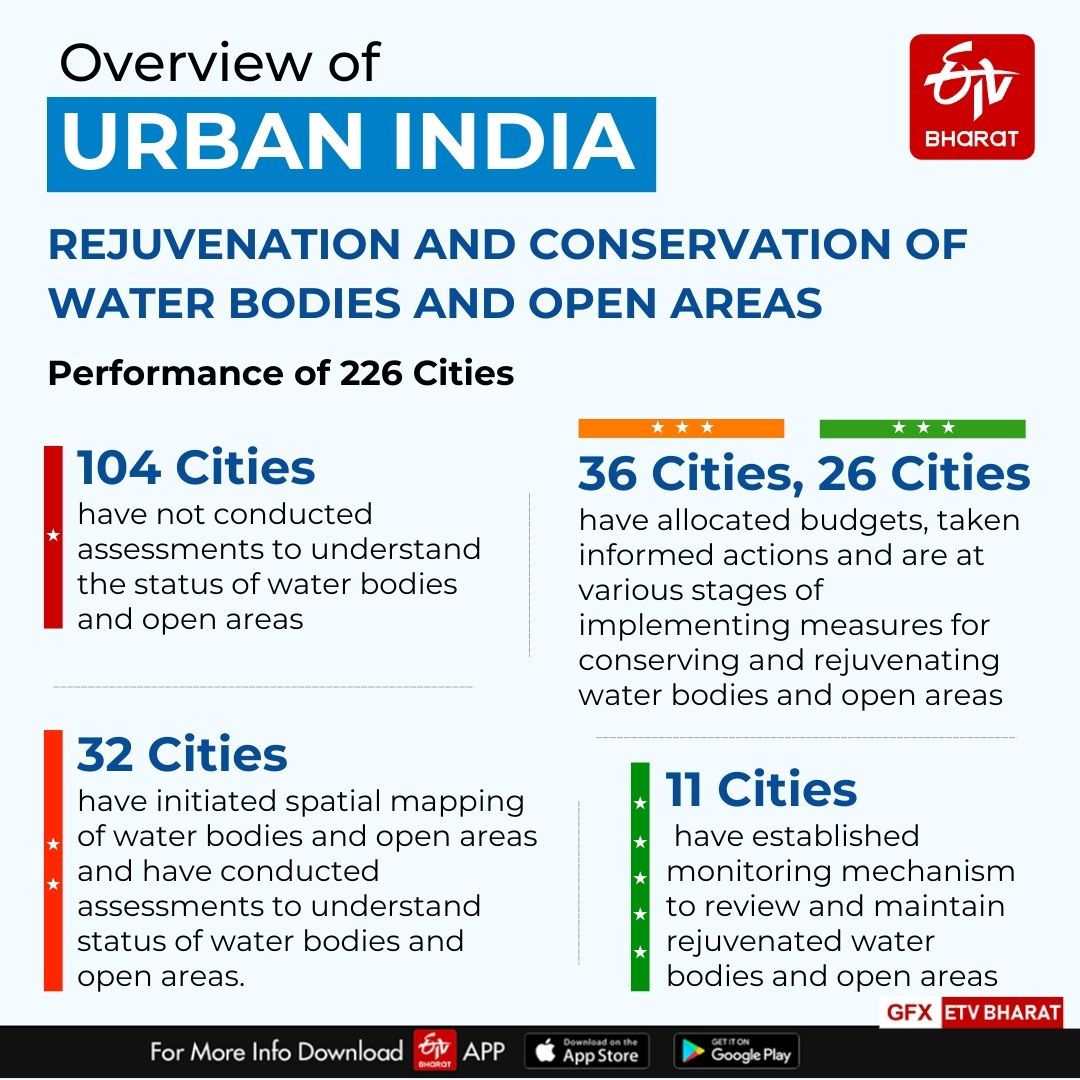

Third, as part of nature-based solutions, the climate action plans largely advocate tree planting and water body management. These plans have failed to fully comprehend the function of ecosystem processes and the importance of ecosystem restoration in climate risk mitigation. Fourth, the prospect of financing climate-resilient projects has remained bleak. Few cities that have prepared climate action plans are reported to spend only two to three percent or even less of their annual budget on climate activities. This is not surprising given the lack of capacity and low awareness about climate plans at the city level.

City governments depend on central and state government schemes for the provision of urban services. However, these schemes do not specify any conditions for the design and maintenance of climate-resilient urban infrastructure. Some cities (e.g. Visakhapatnam, Ghaziabad, Vadodara) have financed their climate projects through combinations of loans from public sector banks and the issue of municipal bonds. Other cities (e.g., Coimbatore) have received support from the international development agencies for awareness and capacity building of the municipal staff and grants for the preparation of climate action plans.

However, owing to their infirm financial health and weak institutional capacity, the city governments in general find it difficult to explore other innovative sources of financing and collaborative avenues. Even in this year’s COP 29 in Baku, the developed countries have pledged only USD 300 billion for climate finance predominantly in the form of loans rather than grants and that too without any clear finance commitment towards the cities. This is inadequate given the magnitude of climate challenges.

Moving Forward

Amidst climate change, Indian cities present opportunities for sustainable urban transformation. As a cause for optimism, some of the cities have embarked on the pathways of climate-resilient urban futures, necessary not only for stimulating economic growth but also for improving quality of life. It is imperative to prepare a city climate plan with a special focus on the people who are in greatest need and exposed to multiple risks.

Meaningful people participation is required to better comprehend and address their vulnerabilities. This would also facilitate data-driven, evidence-based climate action plans. Urban climate action agenda should leverage more nature-based solutions that can be sustained equitably and ecologically over time. This necessitates the capacity building of the city government and the establishment of a dedicated climate cell to coordinate and monitor climate responses. Equally important is to adopt climate budgeting to properly assess the financial requirements. Cities need to be empowered financially so that they can generate revenue from their own sources and better access public as well as private funds.

Read More