India's caste-based discrimination persists in modern institutions, as demonstrated by a Supreme Court judgment condemning the oppressive treatment of prisoners based on caste hierarchies. Government data showing that 92 per cent of workers cleaning urban sewers, septic tanks are from SC, ST, OBC groups — further illustrates the systematic oppression of these communities.

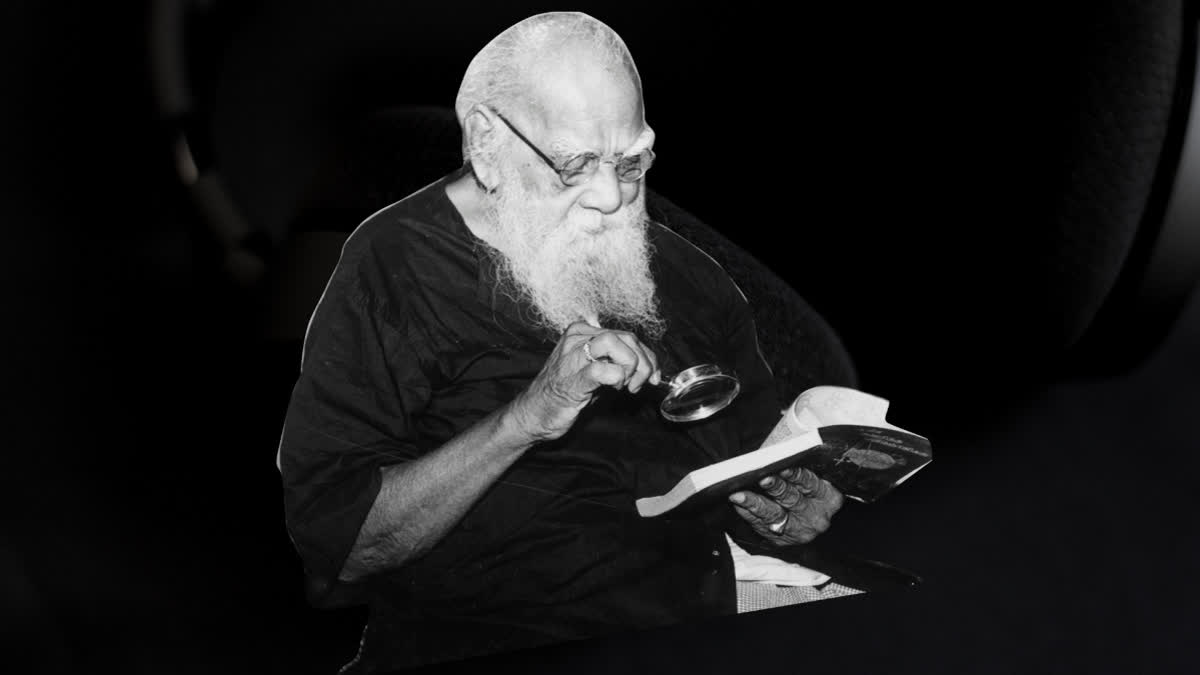

Such realities starkly echo the very injustices that the Self-Respect Movement, led by E.V. Ramasamy (Periyar) in 1925, sought to eradicate. As we approach the centenary of the Self-Respect Movement, it is vital to revisit its origins, contributions, and enduring impact. Launched in 1925 by E.V. Ramasamy (Periyar) in Tamil Nadu, the movement fundamentally altered the political and social fabric of southern India.

Its call for social justice, gender equality, and the annihilation of caste challenged deeply entrenched systems of oppression. Today, as we reflect on a hundred years of its legacy, it is also necessary to examine the role Andhra leaders played, how the movement influenced the Andhra region, and its contemporary relevance in Dravidian states.

Origins and Influence of the Self-Respect Movement

The Self-Respect Movement emerged as a response to the hierarchical nature of Indian society, which was marked by caste oppression and gender inequality. Periyar’s aim was to dismantle Brahmanical hegemony, which dominated social, religious, and political life. The movement advocated rationalism, rejecting the superstitions that supported caste-based hierarchies and perpetuated social injustices. Periyar was deeply influenced by anti-caste reformers like Jyotirao Phule and B.R. Ambedkar, whose ideas echoed the need for social transformation and equality.

Key to the Self-Respect Movement was the promotion of Dravidian identity over an Aryan-dominated narrative. Periyar and his followers advocated for a distinct Dravidian identity to challenge the cultural and political domination of the North. The movement was radical for its time, promoting inter-caste marriages, women’s rights, and the abolition of rituals that perpetuated discrimination. As an organised ideological movement, it sought not only to reform but to revolutionise the way society functioned.

The movement's influence was profound, particularly in Tamil Nadu. Its ideas laid the foundation for Dravidian politics, which took centre stage in post-independence Tamil Nadu through the rise of parties like the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). The Self-Respect Movement redefined the relationship between politics and social justice, carving out a unique political ideology that continues to influence Tamil Nadu’s governance and social policies.

Role of Andhra Leaders and the Self-Respect Movement in the Andhra Region

The Self-Respect Movement's influence spread beyond Tamil Nadu and significantly impacted the neighbouring Andhra region. Many leaders from the Andhra Pradesh region, inspired by the movement’s ideals, worked to propagate its principles. Andhra leaders like Kandukuri Veeresalingam and Raghupati Venkataratnam Naidu had already laid the groundwork for social reform in the region, particularly in challenging caste oppression and advocating women's rights. The Self-Respect Movement gave a renewed push to these efforts.

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Periyar's ideology resonated with the Andhra intelligentsia and reformers, who aligned their social justice goals with the principles of the movement. Leaders like Gora (Goparaju Ramachandra Rao), who later became an important figure in atheism and rationalism in Andhra Pradesh, were influenced by the Self-Respect ideology. The fight against Brahmanical dominance, caste oppression, and superstitions found fertile ground in the Andhra region, which was already experiencing social and cultural shifts.

In Andhra Pradesh, the movement influenced caste-based political mobilisation, particularly among the non-Brahmin castes, and contributed to the formation of a more assertive political identity. It played a role in creating a consciousness that rejected the passive acceptance of social hierarchies and instead advocated for active reform and upliftment of marginalised communities. The seeds of these ideas can be traced to later political developments in Andhra, particularly with the rise of parties like the Telugu Desam Party (TDP), which invoked regional pride and the rights of marginalised communities.