Hyderabad: Mahatma Gandhi’s conception of self-reliance was of simple living and self-sufficiency. The basic idea was to use local resources and a local work force for the production of commodities for local consumption to the extent possible, with minimal dependence on the outside world. But the Indian government’s clarion call for ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ (self-reliant India) has not been matched by steps towards either simple living (especially for the middle and rich class) or local self-sufficiency. After perhaps one of the biggest and strictest lockdowns in the world owing to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, the recently announced relaxations and relief measures aimed at rebooting the economy are likely to take us even further away from the Gandhian value of self-reliance.

In the last couple of months, COVID-19 has shown us how inextricably public health and the economy are linked. Despite the private health sector in India having more ventilators, doctors and hospital beds than the public healthcare sector, it has essentially been public healthcare which — though chronically underfunded and neglected — has been bearing the brunt of the pandemic. The private sector has either been found playing it safe by ‘distancing’ itself from its patients or busy making profits even in this time of humanitarian crisis.

The lockdown has been in force to varying degrees for over two months now, albeit with little consensus on its effectiveness in the absence of concerted government action to build greater healthcare capacity to fight the disease. Because of this disruption, the economy is in a state of chaos. Businesses and industries are failing, and unemployment, hunger and destitution are on the rise. With no clear resolution to the problem in sight, some are predicting economic catastrophe. These events have been a demonstration of how the sustainability and resilience of any economy are hinged on the strength and equitability of its public health system.

The only rational long-term response to this crisis would be to make foundational changes in both our economy and our health system. We must build an economic system which is geared towards distributing wealth and resources more equitably to ensure the right of all people to a secure and dignified life, even during difficult times. We must strive to develop a healthcare system which provides access to quality health services to all, irrespective of social or economic standing. Both will require discarding neoliberal policies and their underlying capitalistic logic, which inevitably put profit over people, even when the very survival of humanity is at stake.

Read: Focus on poor, improve overall healthcare to combat COVID-19: Researchers

It is therefore ironic that the government’s plan to revive the economy includes spending INR 8100 crores to boost private sector investment in social sector infrastructure creation like hospitals and schools. The gates have been opened even wider for private sector investment in the defence, power, space and coal and mining sectors. Despite a strike last year by workers of the Ordnance Factory Board — the world’s largest government-operated defence production organisation — which had stalled attempts at its privatisation, the government recently declared its decision to corporatise the company while announcing a string of economic stimulus measures. Several state governments have moved to suspend labour rights with the hope of attracting investment and recovering lockdown losses. In a bid to improve healthcare facilities, the NITI Aayog has asked states to accelerate the process of setting up of medical colleges on the PPP model and augmenting district hospital facilities with help from private partners. A move which had been criticised as counterproductive even when it was originally proposed a few months ago.

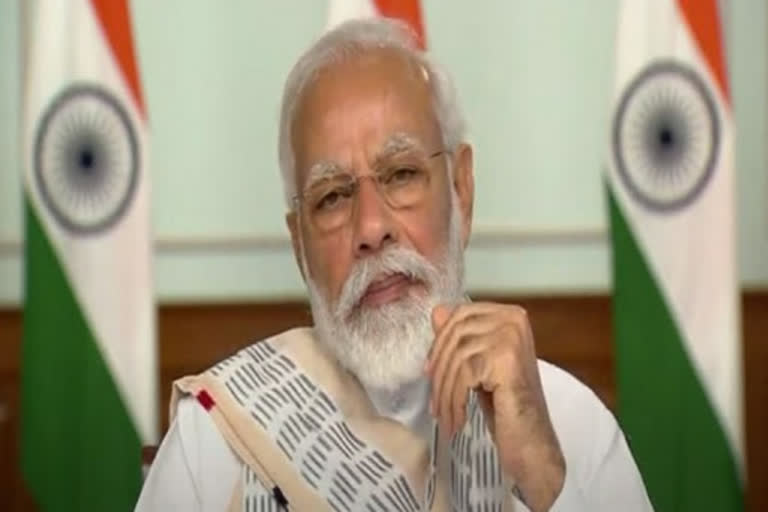

To add to the all-round absurdity, Prime Minister Narendra Modi described this economic stimulus package as part of his “Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan”. It is unclear what stretch of imagination allowed him to view upgrading the foreign direct investment (FDI) limit in defence manufacturing from 49% to 74% as a move towards self-reliance. Former health secretary K Sujatha Rao, in a tweet chiding the NITI Aayog for further privatising public health facilities asked if their definition of Atmanirbhar was “handing over government hospitals to private sector along our tax money” and exhorted them to “wake up” and “look out of your window”.

The government has clearly learnt nothing from this crisis and is keen to go ahead with business as usual. In fact, it appears to be taking advantage of the crisis to push its neoliberal economic agenda much further than would have been possible in normal times, with the full support and encouragement of the capitalist lobby.

Read: In the post coronavirus world, what will be the new normal?

Inviting foreign direct investment is part of the economic policies of privatisation, globalisation and liberalisation which are responsible, if not directly for the spread of the virus, certainly for the mismanagement and insensitivity which have characterised the response of many countries around the world. One striking example of this is how Indian migrant workers had to undertake gruelling journeys on foot on highways, or worse, railway tracks, merely because the government was under pressure from the private industry to not let them leave. The continuing power and influence of this dehumanising ideology, even in the face of the harsh truths brought to light by the current crisis, should send the alarm bells ringing for all of us.

The example of the medical equipment manufacturing industry is a particularly apt one in the present scenario to illustrate how FDI and conventional neoliberal policies are counterproductive in the pursuit of self-reliance. The medical device manufacturing sector has been open to 100% FDI since 2015. Since then, most of the FDI that has come into the country has been to finance imports and trading, build storage and distribution infrastructure, but not to augment domestic manufacturing capabilities. This has allowed international medical equipment manufacturers to reap huge profits by selling their products in the Indian market without making any contribution to local industrial development.

Even today, close to 80% of the medical equipment used in our country, including in government hospitals, is imported. Though there is some manufacturing capacity in non-electronic medical equipment, over 90% of medical electronic products are imported. From the equipment used for the computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound scan, cath lab for heart procedures like angioplasty, endoscopy, colonoscopy, radiation therapy and drugs for chemotherapy to the knife and scissors used in surgery are all procured from countries like Germany and the United States.

Read: Raising government spending: At what cost?

Customs duties on imported medical device products have been very low (0-7.5%) and 40% of the medical electronic products imported are pre-owned (i.e. used, refurbished products which are sold at prices much lower than the market rate). It has also been reported that in government purchases many MSMEs in the sector are not given timely payments, with delays of several months not being uncommon, whereas importers are paid promptly. These policies and practices give foreign companies which export medical devices to India a big advantage over domestic manufacturers.

Further, even the equipment that is currently manufactured in India is often found to be substandard. Because of the unreliability of Indian equipment and medicines, doctors prefer their foreign-made counterparts. In what seems like a mockery of the idea of self-reliance, they sometimes invite tenders for the purchase of these items with restrictions which disqualify Indian companies from even applying.

For years medical equipment manufacturing bodies such as the Association of Indian Medical Devices Industry have been demanding an increase in customs duties, a ban on the import of pre-owned products, preferential pricing of domestically manufactured products and regulation of the MRPs of imported devices, in order to boost domestic manufacturing both in terms of quality and quantity — but to no avail. Reportedly, importers’ lobbies have exercised their influence to block any policy changes.

Read: To Converse with the Marginalized

As the defective rapid antibody test kits from China have shown, not all imported products are of high quality. Further, it is difficult to impose quality standards on products which are being manufactured abroad. There is no reason why India cannot locally manufacture products which meet the highest quality standards.

One important way of improving production quality would be to promote indigenous research and design. Especially in the case of medical research, indigenous research is important because it can help us develop medical technologies which are adapted to local problems in healthcare and relevant to local populations. Currently, medical research in India is severely neglected. According to a study which looked at the research output from 579 Indian medical institutions and hospitals between 2005 and 2014, only 25 (4.3%) of the institutions produced more than 100 papers a year. Compare this with the thousands of research papers published every year by top-notch international institutions like the National Institutes of Health, USA and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Clearly, the government needs to invest more in improving the quality of our public research institutions as well.

The case of the medical devices industry reflects how FDI is not an effective mechanism to promote indigenous manufacturing. The government’s new motto of self-reliance does correctly identify the problem of our excessive reliance on imports which contributes to the fragility and inequity of our economic system. However, the proposed solutions will only worsen this situation. Self-reliance can only be achieved through policy changes which deprioritise the interests of multinational corporations and adopt a people-centric, decentralised approach to industrialisation that improves local economies, drives job growth and supports public research and innovation.