Washington: NASA validated a new type of propellant for spacecraft of all sizes. Instead of toxic hydrazine, now space missions can use a less toxic, "green" propellant and the compatible technologies designed to go along with it.

NASA's Green Propellant Infusion Mission (GPIM) successfully proved a never-before-used propellant & propulsion system work as intended, demonstrating both are practical options for future missions.

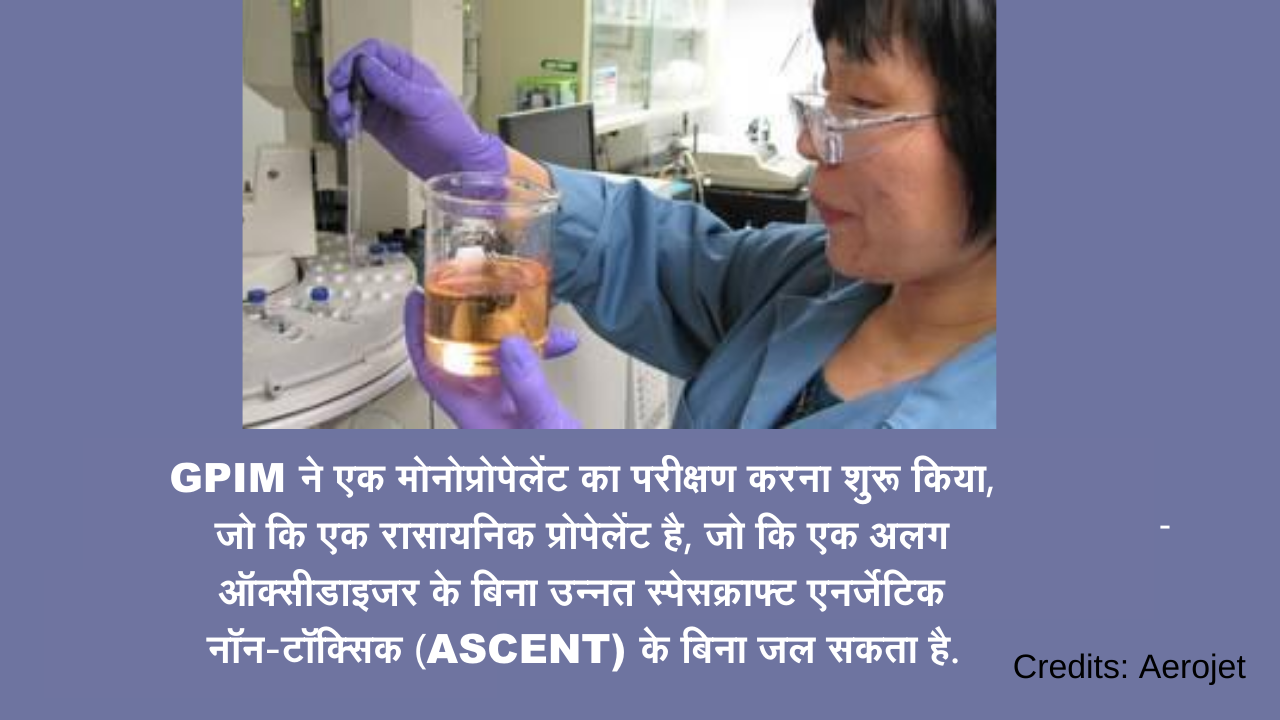

GPIM began to test a monopropellant which is a chemical propellant that can burn by itself without a separate oxidizer called Advanced Spacecraft Energetic Non-Toxic (ASCENT).

Formerly known as AF-M315E, the U.S. Air Force Research Lab invented the propellant at Edwards Air Force Base in California. It is an alternative to the monopropellant hydrazine.

Tim Smith, GPIM mission manager at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama says, “This is the first time in 50 years NASA tested a new, high-performing monopropellant in space. It has the potential to supplement or even replace hydrazine, which spacecraft have used since the 1960s.”

GPIM’s effective demonstration of the propellant paved the way for NASA’s acceptance of ASCENT in new missions. The next NASA mission to use ASCENT will be Lunar Flashlight.

The small spacecraft, which aims to provide clear-cut information about the presence of water deposits inside craters, will launch as a secondary payload on Artemis I, the first integrated flight test of NASA's Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System (SLS) rocket.

Despite being pink in colour, ASCENT is considered to be “green” for its significantly reduced toxicity compared to hydrazine, which needs protective suits and rigorous propellant loading processing procedures. It is safer to store and use, requiring minimal personal protective equipment like lab coats, goggles, and gloves. Besides being easier and less expensive to handle here on Earth, when loading a spacecraft with propellant, for instance, ASCENT will allow spacecraft to travel farther or operate longer with less propellant in their tank, given its higher performance.

But to test the fuel on a small spacecraft, the GPIM team had to develop hardware and systems compatible with the liquid. Aerojet Rocketdyne of Redmond, Washington, designed and built the five thrusters onboard GPIM. Aerojet Rocketdyne and Ball Aerospace of Boulder, Colorado, co-designed the other elements of the propulsion system.

Also Read: NASA spots tiny asteroid buzzing by Earth sets the closest flyby on record

While in orbit, GPIM tested the propellant and propulsion system, including the thrusters, tanks, and valves, by conducting a planned series of orbital maneuvers. Attitude control maneuvers, the process of maintaining stable control of a satellite, and orbit lowering demonstrated the propellant’s pre-mission projected performance, showing a 50 percent increase in gas mileage for the spacecraft compared to hydrazine.

With the technology demonstration objectives almost complete, the mission proved ASCENT and the compatible propulsion system is a viable, effective alternative for NASA and the commercial spaceflight industry, Smith added.

“We can attribute GPIM’s success to a strong partnership,” Smith said. NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate selected Ball Aerospace to lead the mission in 2012. In addition to building the mini-refrigerator-sized spacecraft, the company integrated and tested the payloads and propulsion system before launch and provides flight operations support.

Also Read: Dwarf planet Ceres is water-rich, finds NASA probe

Christopher McLean, GPIM principal investigator for Ball Aerospace said, “We are excited to announce flight operations have been very smooth, with the new propulsion subsystem operating as we anticipated. We greatly appreciate the partnership and continuous support throughout this mission from NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate, and program management office at Marshall.”

The GPIM mission is now approaching completion, and the spacecraft has started a series of deorbiting burns. Approximately seven burns will lower the orbit to about 180 kilometers and deplete the propellant tank.

The small spacecraft will burn up in Earth’s atmosphere upon re-entry, anticipated in late September.

Also Read: Weather will drive the actual date of SpaceX crewed mission," NASA Administrator