Klessin (Germany): Thomas Siepert looks across the verdant grain field, glowing in the sun after a spring thunderstorm, as windmills slowly churn in the distance.

Wild boar piglets trundle across the road into town and a hare pops out and dashes away. Yet the serene scene belies the slaughter there 75 years ago as German troops fought furiously — and futilely — to stave off the Soviet Red Army that was approaching the Nazi capital.

“It seems so idyllic, but it’s a huge cemetery,” Siepert said. “That shouldn’t be forgotten.”

But for decades, many of those who died there were forgotten, some buried where they fell and others dragged by civilians in the months after the war into trenches and foxholes they had themselves dug, and covered over.

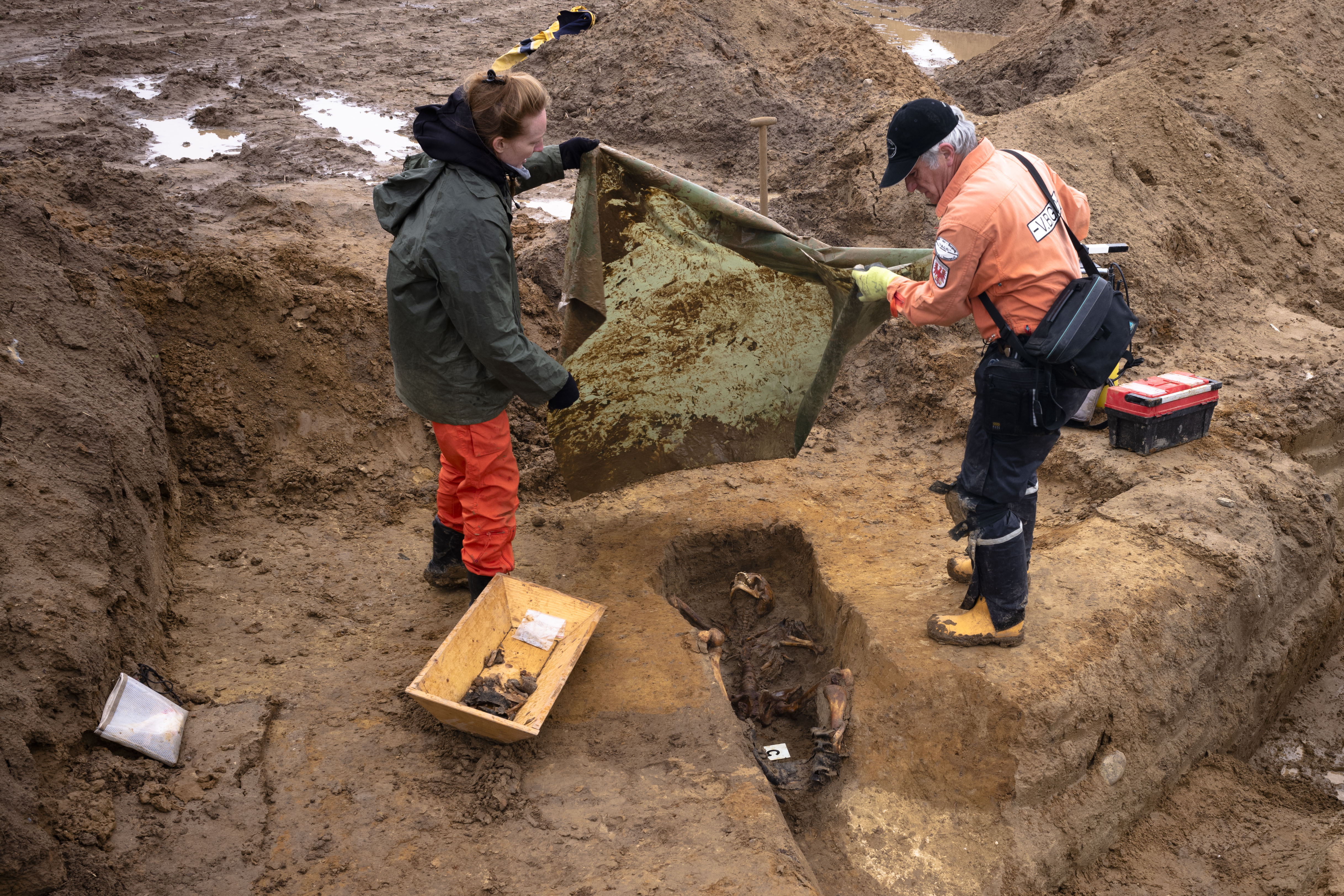

For the last 15 years, volunteers like Siepert from around Europe have been trying to rectify that, devoting vacations to excavating long-buried trench lines and military positions in the search for those who never made it home.

During 19 digs across a square kilometer (less than half a square mile), members of the Association for the Recovery of the Fallen in Eastern Europe have found 116 German and 129 Soviet soldiers.

They seek to identify as many as possible — to provide closure for families, to give the dead their names back, and to separate them from the numbers in the history books in the hope of explaining the cost of war to future generations.

“On all sides, these are destroyed lives. These are all people who died senselessly,” said Albrecht Laue, chairman of the association. “If we talk about a huge slaughter with hundreds of thousands of dead, nobody can understand that. But if I talk about the story of a young 17-year-old soldier, that’s tangible.”

Laue, a 46-year-old businessman from Hamburg, got interested in the search when looking for the grave of his grandfather, which he located near where he died fighting in Russia in 1942 as a young lieutenant. Siepert, 47, an engineer from nearby Frankfurt an der Oder, remembers as a child having regular lectures in school about avoiding the grenades and other munitions still found in the area, and wondering why.

Other volunteers include anthropologists, archaeologists, excavators and the disposal experts needed when munitions are found. They hail from all over, including Russia, Poland, Ukraine, Italy, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

“We couldn’t, and also don’t, want to look for soldiers from a specific nation,” Laue said. “That’s the interesting thing when one finds one of the dead; one never even knows at the beginning if it’s a German or a Soviet."

In February 1945, they were bitter foes.

The village of Klessin sits on a height 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) from the Oder River. German military observers used it to call in artillery strikes on Soviet troops as they streamed across a pontoon bridge in the build-up before the final push on Berlin.

Recognizing the strategic importance of the hamlet, 100 kilometers (60 miles) east of Berlin, the Soviets made it a target. The Nazis resolved to hold it, moving in a unit of soldiers, augmented by officer cadets and older “Volkssturm” militia, scraped up as the number of military-aged men dwindled.

The fighting pitted 400 Germans in Klessin against about four times that number of Soviets, with the Germans supported by a unit of Panther tanks in the neighboring village of Podelzig, nearby artillery and air-dropped supplies.

Fierce combat raged for nearly two months, often hand-to-hand, as the Soviets attempted to take the village, firing off 62,000 mortar rounds and artillery shells.

Exactly how many were killed or listed as missing is not known, but the casualties were enormous, Siepert said.

“On March 20, German troops tried to break through there to make a corridor,” he said, pointing to a field between Klessin and Podelzig where the Soviets had laid a minefield and other defenses after encircling the village. “There were 150 missing from that single attack, as well as 50 killed. Seventy made it through.”

On March 23, 1945, the beleaguered German soldiers attempted a breakout under the cover of darkness. About 60 made it, and the others were captured or killed.

German tank commander Lt. Hans Eimer was listed as missing after the breakout attempt. Eimer had led his Panther tank into Klessin the week before on his 22nd birthday to support the garrison, but the vehicle ended up being knocked out and he was wounded and trapped in the village.

Eimer’s younger brother, Fritz, had died in fighting that January. After the war, his sister Margarete had long urged Laue’s group to try and determine the fate of her only other sibling.

Eimer’s remains were located by Laue’s group in 2016 by chance and identified by dogtags. The group told Margarete before she died in 2018 that her brother had made it 250 meters (yards) out of the village before he was killed, and lay with two other soldiers.

Identifications are rare, especially of the Soviet soldiers who had no dogtags, but occasionally the volunteers get lucky.

In a dig on a Soviet outpost on a hill outside of Klessin in 2018, they came across three Soviet soldiers who were all highly decorated and traced their names through the medals.

Also Read: Amid Moscow lockdown, some dogs find new homes and friends

This year’s spring dig has been postponed due to lockdown restrictions during the coronavirus pandemic. Some work is still underway on a memorial site being established amid the rubble of the original farm buildings.

Hermann Kaiser, a member of the small community association behind the memorial, said he remembered finding military material as a kid growing up in the area, happily throwing on an old steel helmet and fighting “war” with his friends, while not understanding they were playing on graves.

The hope is with the memorial to make sure that others do understand.

“We want to present what happened here 75 years ago, what war means, show the younger generation that war destroys everything,” he said, looking at the cratered landscape and rubble of the memorial. “And if we can do that in the place where it happened, it’s unforgettable.”