Hyderabad: The marked feature of India’s economic boom of the two decades is that it has been fuelled by a huge expansion of debt at all level – Central and State governments, public sector, private sector and households. Though the impact of lockdown is devastating, it may have indirectly turned out to be the saviour of various highly indebted states.

Some of the States were already practically dangerously close to insolvency even before the lockdowns – mostly due to mismanagement and vote bank politics where political parties are distributing money today at the cost of future. All these long-term detrimental activities are claimed to be for the “Welfare of the people”.

States are now borrowing money at ever-increasing rates and often to repay old loans or to fund schemes that will help them win elections rather than create jobs. COVID induced lockdowns only gave an excuse for such states to continue their irresponsible behaviour.

Rising Debt Mountain

During 2019-20, the Central government borrowed about Rs.7 lakh crores while States cumulative borrowed another Rs.6.3 lakh crores – far above their budget estimates. The Central government borrows about 80% of its requirements from the financial markets which include banks, insurance companies, mutual funds, provident funds, small savings, etc.

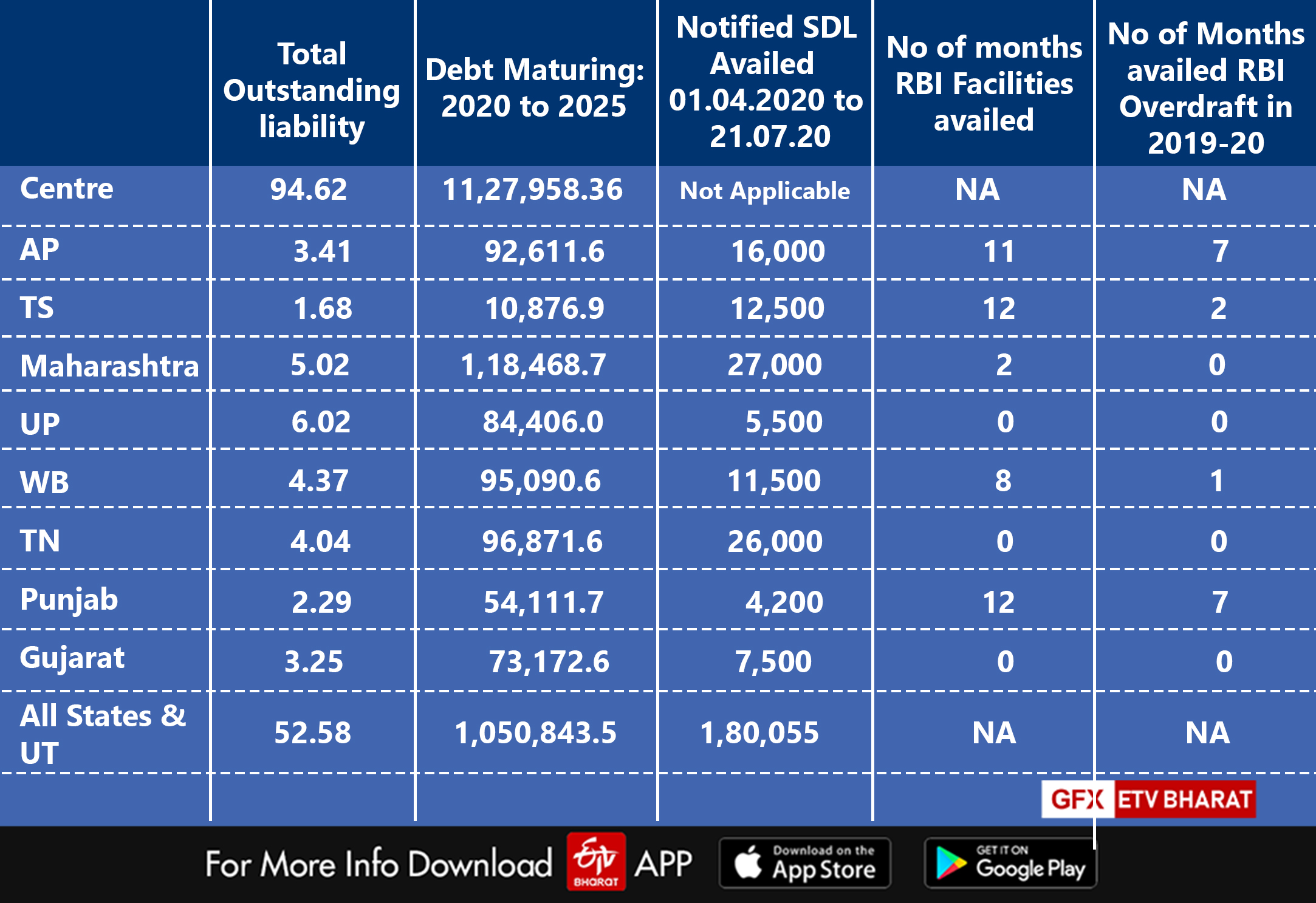

Post-COVID, the centre announced that it will borrow a total of Rs.12 lakh crores in the present financial year – up from the budget estimate of Rs.6 lakh crores. However, it is likely that even this central borrowing will be an understatement since in the first three months the Centre has already borrowed Rs.4.5 lakh crores while the states have already borrowed Rs.1.8 lakh crores as State Development Loans and another Rs.60,000 crores as other short-term borrowings as part of RBI support.

Based on the government estimates the Debt to GDP ratio is expected to touch about 86% up from about 68%. Using Debt – GDP ratio is not a useful metric in a country like India and in these circumstances since (a) sharp fall in GDP makes the comparison worse and, (b) huge poverty means that the burden of indebtedness is on far fewer people than estimated. The net result is that the debts will mean the aim of bringing down Debt-GDP ratio to 60% by 2023 under FRBM Act is a pipedream. This will now not happen until at least 2033.

It is important to note that there is a difference between the borrowings of the Central government and the state government. The Central government has huge assets and all the levers of taxation while the states have very few avenues of increasing their revenues. Hence, it is important to note that divestment can rescue the centre while the states have few assets because since 1991 they have not invested in asset building while most states can barely maintain.

(*Source: Reserve Bank of India Time Series Data)

Impact:

First important consequence is that while expenditure is increasing, revenues are declining even for the central government, which was able to collect only 90% of the revised budget estimates. In March 2020, its receipts were only sufficient to cover 65% of the expenditure. The position of the states was even worse.

GST collections last year were Rs.10.58 lakh crores against the target of Rs.13.1 lakh crores. This year they are expected to be about 20% less. Second, Increased government borrowings are happening at a time of slow down and with COVID the private sector is sharply cutting back on capital investments, which are the lifeline of the economy.

Private investments already touched a decade low even before COVID and it is now expected to decline by another Rs.4 lakh crores this year. This is happening at a time when citizens and business are so worried that they are pulling money out from circulation and depositing it with the banks because of the unwritten government guarantee.

Fear means that banks are not willing to lend to the private sector and believe that lending to the government is better. Further, the demands from governments mean that they are forced to lend to the governments at the cost of the private sector. This is leading to “crowding out” of the private sector from credit markets. Thirdly, most of the states are not investing the money judiciously means it becomes more likely that they may default or to avoid default the centre has to bail them out.

Normally, any borrowings accompanied by public investments in useful economic activity would have created jobs and helped repay the loans in future. Since governments are essentially distributing borrowed money, it is likely that the Indian economy is likely to either stagnate for a long time and in the worst crisis go into another crisis down the road.

Fourthly, under our constitution as per Article 293, the states can borrow only with the permission and approval of the Central government. That means the central government is indirectly responsible for the loans of the States. Since a government cannot be allowed to default en masse, it is likely that the Central government will be forced to keep spending money on bailouts of defaulters including banks and state governments. Since most of India’s borrowings are internal in nature, it will mean that the losers will be depositors in banks, purchasers of insurance policies along with subscribers of EPF and Mutual Funds.

The only way that the centre and states can hope to repay the loans is by massively increasing taxes. More taxes mean less money for consumption and less economic growth – which means fewer jobs. There is little doubt that for the next 5 years, all sections of Indians will end up paying more direct and indirect taxes – something which has started by squeezing out consumers for petroleum products. Taxes tend to affect the lower and middle sections more adversely than the richer sections.

Solution

There are only two ways that the Central government stop a disaster in the making and bring out a semblance of order to this downward debt spiral: there is an urgent need for the Centre to make it clear that either states cannot borrow money for vote bank politics or it should clearly state that every year a fixed percentage (preferably 33%) of the total budget has to go into capital asset building. Alternatively, the least that the Centre can do is to limit money distribution for vote bank politics to a maximum of 33% of the total own revenues of the states. That will at least start the journey towards financial discipline by the states.

Article by Dr S Anand, an expert on centre-state finances