Hyderabad: Absolute "no mercy", "public execution as we can't wait for the law to take its course" -- statements such as this coming from an elected MP and Shiv Sena leader Sanjay Raut in the public discourse can be prickly. Raut was speaking on the Shraddha murder case. While it may satisfy the collective conscience and fulfills the immediate gratification of the masses, it also reeks of spitefulness instead of opting for corrective measures and identifying the root cause of the problem.

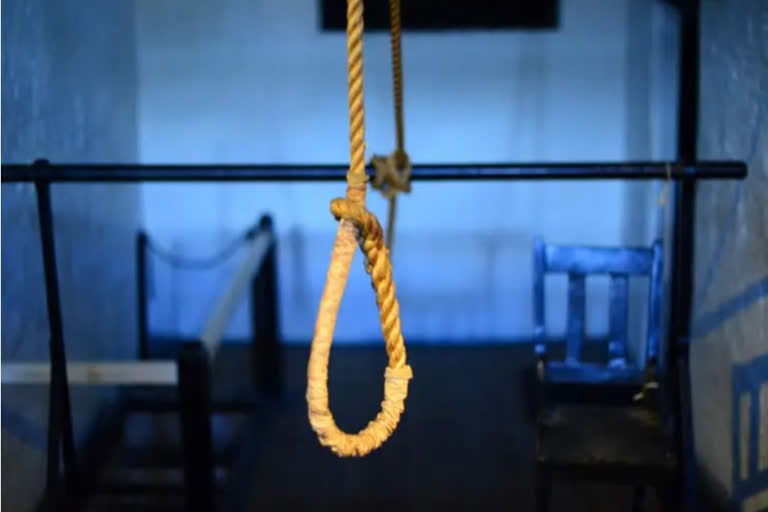

At a time when public floggings have become the order of the day with prime-time anchors thumping their chests and dictating what the code of morals should be in India, discussions of public execution reflect traits of a theocratic state and not of a country with the world's largest democracy. This also brings up the age-old debate of whether capital punishment and other punitive measures actually rid society of heinous crimes such as this.

At the recently held Universal Period Review (process), a peer-based evaluation mechanism, where India's human record was evaluated, several countries from Australia to Chile suggested India "put a formal moratorium on the use of the death penalty". In response, solicitor general Tushar Mehta defied: "The death penalty is only imposed in rarest of rare cases when the alternative option is unquestionably foreclosed when the crime committed is so heinous that it shocks the conscience of society".

Although, in a world of artificial intelligence and social media where ideas and opinions are shaped by what is being talked about on these platforms, institutions too can ride on the public sentiments and get swayed by them.

Why death penalty should be abolished?

-- Factually speaking, over the centuries there have been ample examples of why it is not a deterrent. The American Civil Liberties Union opines: "the death penalty has no deterrent effect". In the US, "states that have death penalty laws do not have lower crime rates or murder rates than states without such laws. And states that have abolished capital punishment show no significant changes in either crime or murder rates."

-- Death penalty is also used as a political tool, sometimes against political opponents with ideological differences like in Iran and Sudan, in other instances to pacify the public's idea of "an eye for an eye" such as in this case or Nirbhaya's -- the Delhi rape case.

-- Amnesty International opposes the death penalty. It says: "The death penalty violates the most fundamental human right – the right to life. It is the ultimate cruel, inhuman, and degrading punishment." It further adds, "When the death penalty is carried out, it is final. An innocent person may be released from prison for a crime they did not commit, but execution can never be reversed."

Marie Deans was called an "angel of death row" and fought for convicts who were awarded death punishment. Her most famous case was the falsely convicted prisoner — Earl Washington Jr. — from Virginia’s death row. Deans saved the man, who couldn't afford an appeals lawyer for himself. He was convicted for raping and murdering a Culpeper mother in 1982. All this came from a personal tragedy when, in 1972, her own mother-in-law Penny Deans was murdered. Deans remembered the police officer investigating the case saying, "We’ll find the bastard and fry him." To which she said, "Capture him, but don't kill him for me".

"He had a family, too," she had told The Washington Post in 1989. "If he was executed, it would be another murder. It would be worse in a way, because he would be put on death row and the family would have been told every day for 10 years — or eight years or six years or however long it takes — that he was going to be killed. I think that’s worse."

"Revenge is not the answer. The answer lies in reducing violence, not causing more death," she had told to Amnesty International. An argument is that capital punishment instills a sense of fear and thus lowers the crime rate. Studies suggest that criminals, in fact, shed all their inhibitions in committing the crime. In countries where it has been abolished, crime has not risen while in other cases the rate has even dipped. For instance in Canada, the murder rate was reduced to half what it was in 1976 when the country decided to do away with the death penalty.

In Resistance, Rebellion and Death, Albert Camus criticized capital punishment: "The death penalty, which really neither provides an example nor assures distributive justice, simply usurps an exorbitant privilege by claiming to punish an always relative culpability by a definitive and irreparable punishment."

It probably is just as wrong to take Aftab's life as it was wrong of him to take Shraddha's. Data aside, capital punishment is not a moral practice. It's morbidly archaic and reeks of a sense of superiority. It comes from the sense of ownership of someone. What the criminal did was a crime, how can a similar act be called justice?