Hyderabad: Two universal minds of twentieth-century India had a varied opinion on several issues. They differed, went poles apart on many things, yet got on the same boat for a common cause – freedom.

Rabindranath Tagore and Gandhi differed, debated, had a completely different outlook towards many issues ranging from the attainment of self-rule of Swaraj to the ways in which our freedom struggle would progress.

Gandhi's persisting inkling towards divine intervention and explanation in solving or understanding issues was challenged many times by Tagore.

Time and again the two visionaries, who were pragmatists no less, differed sharply on strategies of mobilisation and their ethical ramifications. Their differences of opinion were ideological and philosophical in the larger sense of these terms.

Both saw the historical foundation of an integral Indian civilisation, in the villages. For both, true self-sufficiency went beyond dethronement of the British Raj. It entailed decolonising and re-empowering the rural man in India economically, socially and culturally, no less than politically.

Gandhi prioritised attainment of Swaraj as the immediate and necessary stepping stone towards a bold and free India. For Tagore, Swadeshi Samaj was largely a matter of creative growth and evolution independent of incumbent political dispensation, foreign or home-grown.

Thus, even as Gandhi gave a call to all his young compatriots to join the Non-Cooperation movement, Tagore desisted on the ground that sacrifice of young lives and minds at the altar of anarchy and negation would be irresponsible and damaging in the long run.

To Gandhi, the charkha or spinning wheel was an essential rallying point, a powerful token of constructive protest combining pragmatic principles of austerity, indigenous simplicity and righteous defiance against foreign economic exploitation.

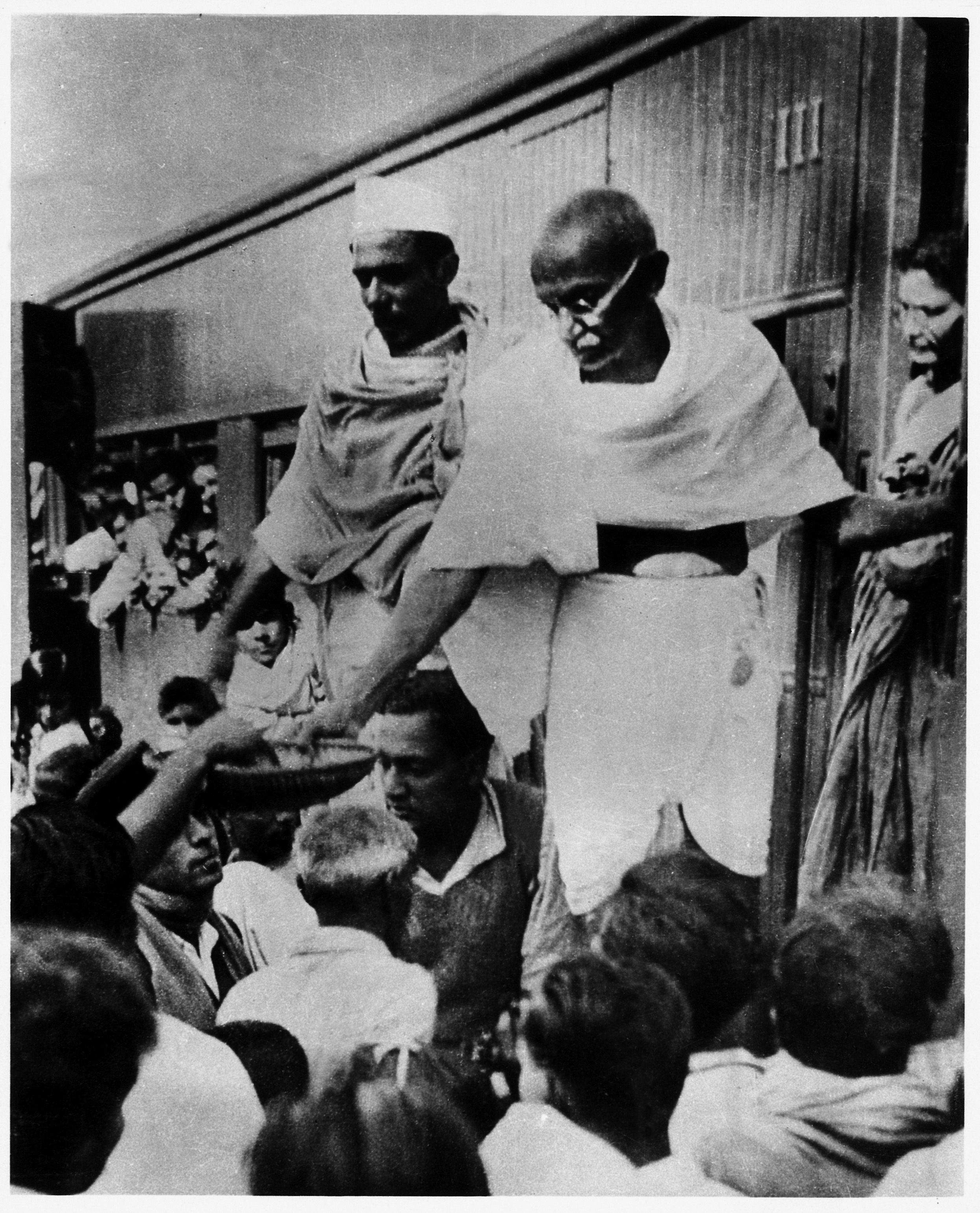

Gandhi and Tagore were two different personalities who came together for the cause of freedom Tagore had reservations about the efficacy of such tokenism. In his view, there could be no fundamental conflict of interest between considered use of evolving global technologies – Vishnu’s Chakra as he chose to call it - and India’s progress towards healthy self-reliance.

Again, Gandhi would steadfastly claim that the earthquake that devastated Bihar in 1934 was an act of divine reprimand and retribution for atrocities related to untouchability.

Tagore expressed concern over the long-term dangers of instrumentalising Indian society’s susceptibility to superstitious obscurantism. Gandhi, however, maintained that it was beyond human intellectual powers to read God’s will so decisively as to rule out moral causality in apparently natural phenomena.

The substantial correspondence that has survived – comprising private messages as well as open letters published in Young India and Modern Review – is remarkable for the way in which these two great minds – and souls – were able to argue and disagree with as much civility as force, without detracting either from mutual regard or their shared commitment to the national cause.

But, the difference never came in the way of Tagore’s lofty regard for the ‘Mahatma’, which is evident from this title, which he himself conferred on Gandhi as early as 1915. It stemmed from their common emphasis on battling inner enemies with the armour of Karna, as it were, rather than on combative nationalism. Gurudev would write to their mutual friend C.F. Andrews that Gandhi was Narayan, whom India in its Satyagraha, its own war for justice and Dharma, would do well to choose over Narayan Sena. Interestingly, Gandhi had also designated as Tagore as, the 'Sentinel'.

A case in point would be their respective responses to the Jallianwallah Bagh massacre of 1919. Tagore renounced his Knighthood as a personal gesture of protest. Gandhi too would surrender his honorary medals and then start a nationwide fund-raising campaign towards a memorial at the site of the massacre.

Looking back, we see that for four months in 1914-15, Rabindranath Tagore’s school in Santiniketan hosted boys from Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s school at Phoenix, Durban, South Africa, pending his arrival.

The empathy in the poet’s gesture and the leader’s enduring gratitude in return set the tone for a warm and rich friendship spanning the three most eventful decades in India’s struggle for freedom and self-rule.

Tagore would visit Sabarmati Ashram in 1920. Gandhi, in turn, would visit Santiniketan for the first time in 1925 and then again in 1940. While the poet was unflinching in providing moral support to the leader through periods of fasting and incarceration, Gandhi was just as generously instrumental in raising as much as 60,000 Rupees for Visva-Bharati.

Interestingly, in 1930, Tagore had himself espoused a comparably abstract idea of a universal mind encompassing all terrestrial existence against Albert Einstein’s scientific materialism.

This equal friendship between two distinct minds helped shape the ‘public sphere’, so crucial to the proud legacy of democratic modernity – for which India stands out among her neighbours to this day.

On the other hand, the issues that they debated, namely the challenges of reconciling the vision that is India and its tangled realities, are of continued relevance even in millennial India.

Ananya Dutta Gupta teaches at the Department of English, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan.

While war and urban culture in the European Renaissance remain her core area of research, her interest in Tagorean thought has lately paved her explorations in India’s intellectual history.

Read:| Panicked by Gandhi's arrival in C'garh, officials repealed anti-farmer orders

Hyderabad: Two universal minds of twentieth-century India had a varied opinion on several issues. They differed, went poles apart on many things, yet got on the same boat for a common cause – freedom.

Rabindranath Tagore and Gandhi differed, debated, had a completely different outlook towards many issues ranging from the attainment of self-rule of Swaraj to the ways in which our freedom struggle would progress.

Gandhi's persisting inkling towards divine intervention and explanation in solving or understanding issues was challenged many times by Tagore.

Time and again the two visionaries, who were pragmatists no less, differed sharply on strategies of mobilisation and their ethical ramifications. Their differences of opinion were ideological and philosophical in the larger sense of these terms.

Both saw the historical foundation of an integral Indian civilisation, in the villages. For both, true self-sufficiency went beyond dethronement of the British Raj. It entailed decolonising and re-empowering the rural man in India economically, socially and culturally, no less than politically.

Gandhi prioritised attainment of Swaraj as the immediate and necessary stepping stone towards a bold and free India. For Tagore, Swadeshi Samaj was largely a matter of creative growth and evolution independent of incumbent political dispensation, foreign or home-grown.

Thus, even as Gandhi gave a call to all his young compatriots to join the Non-Cooperation movement, Tagore desisted on the ground that sacrifice of young lives and minds at the altar of anarchy and negation would be irresponsible and damaging in the long run.

To Gandhi, the charkha or spinning wheel was an essential rallying point, a powerful token of constructive protest combining pragmatic principles of austerity, indigenous simplicity and righteous defiance against foreign economic exploitation.

Gandhi and Tagore were two different personalities who came together for the cause of freedom Tagore had reservations about the efficacy of such tokenism. In his view, there could be no fundamental conflict of interest between considered use of evolving global technologies – Vishnu’s Chakra as he chose to call it - and India’s progress towards healthy self-reliance.

Again, Gandhi would steadfastly claim that the earthquake that devastated Bihar in 1934 was an act of divine reprimand and retribution for atrocities related to untouchability.

Tagore expressed concern over the long-term dangers of instrumentalising Indian society’s susceptibility to superstitious obscurantism. Gandhi, however, maintained that it was beyond human intellectual powers to read God’s will so decisively as to rule out moral causality in apparently natural phenomena.

The substantial correspondence that has survived – comprising private messages as well as open letters published in Young India and Modern Review – is remarkable for the way in which these two great minds – and souls – were able to argue and disagree with as much civility as force, without detracting either from mutual regard or their shared commitment to the national cause.

But, the difference never came in the way of Tagore’s lofty regard for the ‘Mahatma’, which is evident from this title, which he himself conferred on Gandhi as early as 1915. It stemmed from their common emphasis on battling inner enemies with the armour of Karna, as it were, rather than on combative nationalism. Gurudev would write to their mutual friend C.F. Andrews that Gandhi was Narayan, whom India in its Satyagraha, its own war for justice and Dharma, would do well to choose over Narayan Sena. Interestingly, Gandhi had also designated as Tagore as, the 'Sentinel'.

A case in point would be their respective responses to the Jallianwallah Bagh massacre of 1919. Tagore renounced his Knighthood as a personal gesture of protest. Gandhi too would surrender his honorary medals and then start a nationwide fund-raising campaign towards a memorial at the site of the massacre.

Looking back, we see that for four months in 1914-15, Rabindranath Tagore’s school in Santiniketan hosted boys from Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s school at Phoenix, Durban, South Africa, pending his arrival.

The empathy in the poet’s gesture and the leader’s enduring gratitude in return set the tone for a warm and rich friendship spanning the three most eventful decades in India’s struggle for freedom and self-rule.

Tagore would visit Sabarmati Ashram in 1920. Gandhi, in turn, would visit Santiniketan for the first time in 1925 and then again in 1940. While the poet was unflinching in providing moral support to the leader through periods of fasting and incarceration, Gandhi was just as generously instrumental in raising as much as 60,000 Rupees for Visva-Bharati.

Interestingly, in 1930, Tagore had himself espoused a comparably abstract idea of a universal mind encompassing all terrestrial existence against Albert Einstein’s scientific materialism.

This equal friendship between two distinct minds helped shape the ‘public sphere’, so crucial to the proud legacy of democratic modernity – for which India stands out among her neighbours to this day.

On the other hand, the issues that they debated, namely the challenges of reconciling the vision that is India and its tangled realities, are of continued relevance even in millennial India.

Ananya Dutta Gupta teaches at the Department of English, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan.

While war and urban culture in the European Renaissance remain her core area of research, her interest in Tagorean thought has lately paved her explorations in India’s intellectual history.

Read:| Panicked by Gandhi's arrival in C'garh, officials repealed anti-farmer orders

Intro:Body:

L:\Picture-Library\GETTY IMAGES\Gandhi ji 02 oct\PIC

Mahatma and Gurudev: ‘Lofty Soul’ and ‘Great Sentinel’

By Ananya Dutta Gupta

Two universal minds of twentienth century India had a varied opinion on several issues. They differed, went poles apart on many things, yet got on the same boat for a common cause – freedom.

Rabindranath Tagore and Gandhi differed, debated, had completely differing outlook towards many issues ranging from attainment of self-rule of Swaraj to the ways in which our freedom struggle would progress.

Gandhi's persisting inkling towards divine intervention and explanation in solving or understanding issues, was challenged many a times by Tagore.

Time and again the two visionaries, who were pragmatists no less, differed sharply on

strategies of mobilisation and their ethical ramifications. Their differences of opinion were

ideological and philosophical in the larger sense of these terms.

Both saw the historical foundation of an integral Indian civilisation, in the villages. For both, true

self-sufficiency went beyond dethronement of the British Raj. It entailed decolonising and re-

empowering the rural man in India economically, socially and culturally, no less than politically.

Gandhi prioritised attainment of Swaraj as the immediate and necessary stepping stone towards a bold and free India. For Tagore, Swadeshi Samaj was largely a matter of creative growth and evolution independent of incumbent political dispensation, foreign or home-grown.

Thus, even as Gandhi gave a call to all his young compatriots to join the Non-Cooperation

movement, Tagore desisted on the ground that sacrifice of young lives and minds at the altar of

anarchy and negation would be irresponsible and damaging in the long run.

To Gandhi, the charkha or spinning wheel was an essential rallying point, a powerful token of

constructive protest combining pragmatic principles of austerity, indigenous simplicity and

righteous defiance against foreign economic exploitation. Tagore had reservations about the

efficacy of such tokenism. In his view, there could be no fundamental conflict of interest

between considered use of evolving global technologies – Vishnu’s Chakra as he chose to call it - and India’s progress towards healthy self-reliance.

Again, Gandhi would steadfastly claim that the earthquake that devastated Bihar in 1934 was

an act of divine reprimand and retribution for atrocities related to untouchability. Tagore

expressed concern over the long-term dangers of instrumentalising Indian society’s

susceptibility to superstitious obscurantism. Gandhi, however, maintained that it was beyond

human intellectual powers to read God’s will so decisively as to rule out moral causality in

apparently natural phenomena.

The substantial correspondence that has survived – comprising private messages as well as

open letters published in Young India and Modern Review – is remarkable for the way in which

these two great minds – and souls – were able to argue and disagree with as much civility as

force, without detracting either from mutual regard or their shared commitment to the national

cause.

But, the difference never came in the way of Tagore’s lofty regard for the ‘Mahatma’, which is evident from this title, which he himself conferred on Gandhi as early as 1915. It stemmed from their common emphasis on battling inner enemies with the armour of Karna, as it were, rather than on combative nationalism. Gurudev would write to their mutual friend C.F. Andrews that Gandhi was Narayan, whom India in its Satyagraha, its own war for justice and Dharma, would do well to choose over Narayan Sena. Interestingly, Gandhi had also designated as Tagore as, the 'Sentinel'.

A case in point would be their respective responses to the Jallianwallah Bagh massacre of

1919. Tagore renounced his Knighthood as a personal gesture of protest. Gandhi too would

surrender his honorary medals and then start a nationwide fund-raising campaign towards a

memorial at the site of the massacre.

Looking back, we see that for four months in 1914-15, Rabindranath Tagore’s school in Santiniketan hosted boys from Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s school at Phoenix, Durban, South Africa, pending his arrival.

The empathy in the poet’s gesture and the leader’s enduring gratitude in return, set the tone for

a warm and rich friendship spanning the three most eventful decades in India’s struggle for

freedom and self-rule.

Tagore would visit Sabarmati Ashram in 1920. Gandhi in turn would visit Santiniketan for the

first time in 1925 and then again in 1940. While the poet was unflinching in providing moral

support to the leader through periods of fasting and incarceration, Gandhi was just as

generously instrumental in raising as much as 60,000 Rupees for Visva-Bharati.

Interestingly, in 1930, Tagore had himself espoused a comparably abstract idea of a universal

mind encompassing all terrestrial existence against Albert Einstein’s scientific materialism.

This equal friendship between two distinct minds helped shape the ‘public sphere’, so crucial to

the proud legacy of democratic modernity – for which India stands out among her neighbours to

this day. On the other hand, the issues that they debated, namely the challenges of reconciling

the vision that is India and its tangled realities, are of continued relevance even in millennial

India.

Ananya Dutta Gupta teaches at the Department of English, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan.

While war and urban culture in the European Renaissance remains her core area of

research, her interest in Tagorean thought has lately paved her explorations in India’s

intellectual history.

Ananya Dutta Gupta, Ph.D.

Associate Professor

Department of English

Visva-Bharati

Conclusion: