Hyderabad: "I claim to be a practical idealist," Mahatma Gandhi once said. Explaining how life and its problems taught him many lessons, Gandhiji dismissed any claim of having discovered a new philosophy or message for humankind. "I have nothing new to teach the world," he declared, "truth and non-violence are as old as the hills."

In his tireless pursuit of truth, he learnt from his experiments and errors as well. Truth and non-violence constituted the main tenets of his philosophy. But in a discussion with a Jain seer, Gandhiji admitted that by instinct he was truthful but not non-violent. "I have been truthful but not non-violent. There is no dharma higher than truth. Ahimsa is the highest duty," the Mahatma said.

Cautioning his disciples and followers against making an attempt to promote 'Gandhism' and publicising his ideas, Gandhiji said: "There is no such thing as Gandhism. I do not want to leave any sect after me."

Nor was there any need to promote Gandhian ideals through propaganda. "No literature or propaganda is needed about it. Those who believe in the simple truths I have laid down can propagate them by living them. Right action contains its own propaganda and needs no other," he explained.

As Ronald Duncan put it, Gandhiji was the most practical man who would always drive any thought to its personal implication and practical application.

Satyagraha or Sarvodaya, truth or ahimsa —- every ideal he set for himself was first tested in the laboratory of his mind. Science was as important for him as religion. There was no conflict between them. His spirituality synthesized science, religion and philosophy.

If Satyagraha ennobles the human spirit, Sarvodaya brings all people—the rich and the poor, the employer and the employee, the tallest and the lowest - together 'in the silken net of love.'

The need is to control the root of all problems - the human mind. "The mind," wrote Gandhiji, "is a restless bird; the more it gets, the more it wants and still remains unsatisfied." A simple yet meaningful life is possible only when the mind is tranquil. Restraint holds the key to human development. Highest perfection is unattainable without highest restraint, he stated.

Explaining the meaning of selfless action, the Mahatma quoted from the Gita and said: "The sages say that renunciation means foregoing an action which springs from desire and relinquishing means the surrender of its fruit."

Politics and economics are vital for human progress. Politics cannot be a taboo forever. Eschew politics of power but not politics of service, he exhorted. Politics without religion (ethics) is dirt. True economics stands for social justice. It promotes the good of all equally including the weakest and is indispensable for decent life.

The goal of both politics and economics is the welfare of all, not of a particular section or even the majority of the people for that matter.

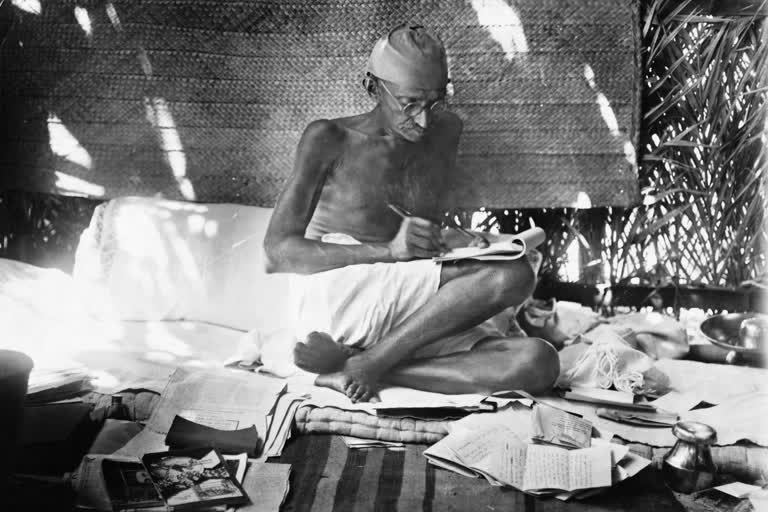

In a land of paradoxes, Gandhiji conceded, he was the biggest paradox. The man with a modern outlook wore just loin cloth and carried the spinning wheel wherever he went.

His capacity for enduring pain and suffering and insults and indignities was boundless. That was why Einstein called him 'the miracle of a man.'

Gandhiji also had that extraordinary gift of laughing at himself. Referring to the spinning wheel he once said: "People have laughed at my spinning wheel and an acute critic once observed that when I died the wheels would serve to make the funeral pyre. That, however, has not shaken my faith in the spinning wheel."

But Gandhiji was quick to add that if "I can provide full employment to our people without the help of khadi and village industries, I am prepared to wind up my constructive work in this sphere."

Three years after Gandhiji’s assassination, a poignant endorsement was made by Acharya Vinoba Bhave, who declared that if the state could find other avenues of employment he would have "no hesitation in burning his wooden charkha to cook one day’s meal!"

The Mahatma was not against machines and modernization. He would welcome the machine that lightens the burden of the people living in cottages and would ‘prize every invention made for the benefit of all'. What he opposed was the craze for the multiplication of machinery and accumulation of wealth without any concern for the starving millions.

He practised what he preached and preached ideals that can be acted upon. His 150th birth anniversary is an occasion for us to reflect on the everlasting relevance of his work and ideals and offer our gratitude to the Mahatma for bequeathing to us such a treasure. May we grow to be worthy of it.