Kendrapara: In Odisha’s Kendrapara district, a storm of controversy surrounds government-sponsored welfare programs meant to nourish the most vulnerable—pregnant women and young children. Allegations of worm-infested sattu (Chhatua in Odia - a nutritional supplement) have surfaced, raising serious questions about negligence, corruption, and the lack of accountability in welfare distribution. Beneficiaries allege the system does not prioritize their well-being.

The Complaints: Worms in Sattu packets

The scandal first broke during the Vikas Mela, a district-level development fair held in Marsaghai block to commemorate the government’s 100th day in office. Beneficiaries from Jalapok panchayat reported shocking incidents of worm-infested food supplies. Among them, Damayanti Maharana of Kanibanka village recounted, “The packet given to us by the Anganwadi worker was full of worms. My 2-year-old daughter ate it unknowingly and began vomiting. The doctor confirmed the illness was caused by contaminated food.”

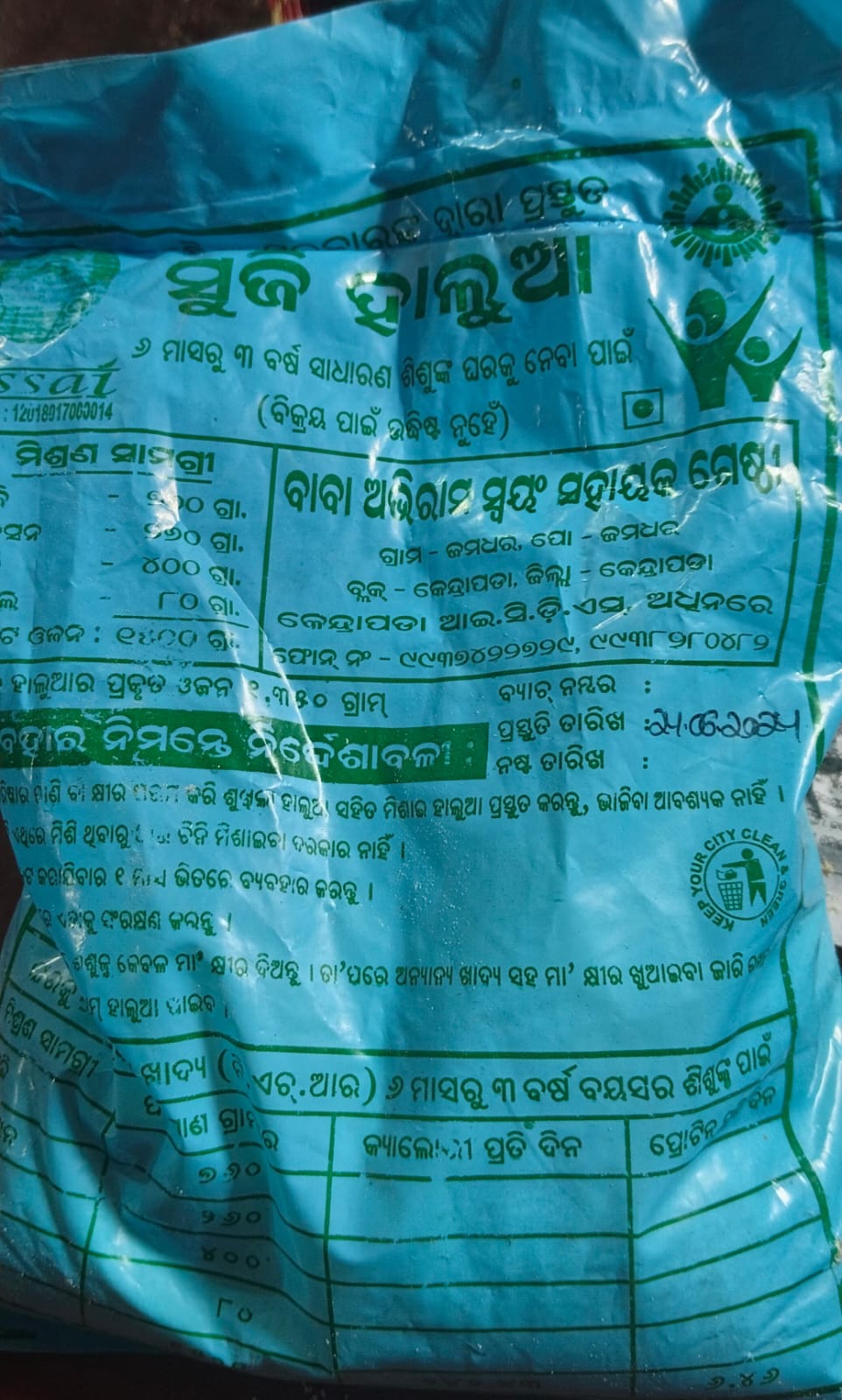

Other complaints included worm-ridden chickpeas and discrepancies in the packaging of sattu. “The date on the packets often does not match the date of distribution. These supplies, unfit for human consumption, are poisoning our children instead of nourishing them,” said Damayanti.

The issue is not limited to food supplies. Provided under welfare schemes, these nutritional supplements have drawn severe criticism. Daily complaints allege worm infestations and substandard quality, raising concerns about how such materials pass quality checks. With 14 companies involved in blanket production for the district, lapses in oversight appear rampant.

Substandard Supplies: A Systemic Failure

According to social worker Bidhubhushan Mohapatra, the problem stems from a deeper issue: the outsourcing of sattu preparation to groups allegedly run by mafias in the guise of self-help groups (SHGs). “Instead of including essential ingredients like wheat, gram, and almonds, these groups are using cheaper substitutes like rice. The result is a product that is not only nutritionally inadequate but also hazardous to health,” he said.

Blankets, too, have come under scrutiny. The lack of proper inspection has led to the distribution of poor-quality materials. “The sattu packs supposed to be nutritious are riddled with worms, making them a health risk for children and mothers alike,” said Mohapatra.

The Deputy Chief Minister’s Response

When confronted with these allegations during her August visit to Kendrapara, Deputy Chief Minister Pravati Parida had promised swift action. After attending a programme at Kendrapara Autonomous College, the CM assured, “This question was raised in the assembly during session and a lot of discussions were held on this. The government will not tolerate any compromise on the quality of food provided to children and pregnant women. We are tracking these suppliers and will ensure accountability,” she said.

However, four months later, no concrete steps have reportedly been taken to address the issue. Beneficiaries and social workers alike express frustration over the delay, viewing it as an indication of systemic apathy.

The Role of Self-Help Group

At the center of the controversy is the Trinath Self-Help Group, accused of supplying substandard sattu. Investigations revealed discrepancies in their operations. While the group is officially listed as the supplier, actual production reportedly occurs at unauthorized locations, raising questions about transparency and accountability.

In a defensive statement, Sasmita Nayak, secretary of the Trinath SHG, said, “We follow government guidelines for preparing and distributing chhatua. People make different allegations, but we are doing our best. Complaints about worms and quality issues are baseless.”

Despite her claims, the group’s license had previously been revoked in 2020, only to be reinstated in 2021. This back-and-forth raises serious questions about the criteria for awarding such contracts and the mechanisms in place for monitoring them.

“The officials responsible for overseeing production are failing in their duties. How can such packets be distributed without proper quality checks?” asked Mohapatra.

The Administration’s Stand

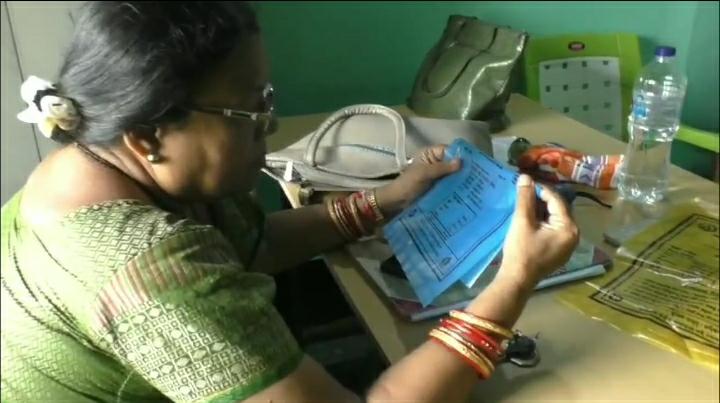

District Social Welfare Officer Manorama Swain confirmed receiving multiple complaints. “In Kendrapara, 14 SHGs supply nutritional supplements including chhatua to 15,620 mothers and 46,989 children. Mixing of ingredients for the preparation is supposed to happen under strict supervision on the 23rd of every month. Despite this, lapses have occurred, and investigation is underway,” she said.

However, the officer’s assurances do little to assuage public concern. Activists argue that without systemic changes, such issues will persist. “Temporary fixes are not enough. We need a transparent, accountable system to ensure quality in welfare supplies,” said Mohapatra.

The Bigger Picture: A Call for Reform

This controversy highlights deeper flaws in the implementation of welfare schemes. The reliance on SHGs and private groups for production has created a system susceptible to corruption and negligence. Beneficiaries, the intended recipients of these programs, are often left helpless in the face of bureaucratic inefficiency, Mohapatra adds.

"The government must address these issues head-on," he says. Stricter quality control, better oversight, and harsher penalties for negligence are crucial. Moreover, empowering beneficiaries to report issues without fear of retaliation could create a more transparent system, adds the social worker.