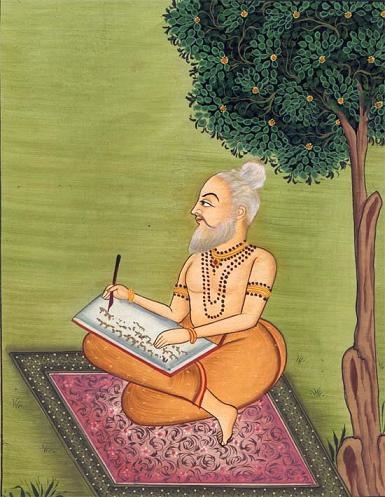

Is ‘Uttara Rāmāyaṇa’ – or ‘Uttara Kāṇḍa’ of Rāmāyaṇa – a genuine part of the epic? Did Maharṣi Vālmīki actually author it? Scholars have researched and debated this question for centuries.

The popularity of the kāṇḍa has been propelled by the emotionally appealing story of the renunciation of Sīta and that of the two princes Kuśa and Lava. However, are there clues that help us resolve the question? Let us inquire into this contentious topic.

Arguments from ‘mandaramu’

In his seminal work on Rāmāyaṇa titled ‘mandaramu’ (a kalpavṛkṣa, or a tree that grants everything), Vaasudaasa Swamy asserts that Uttara Kāṇḍa forms an authentic part of Rāmāyaṇa, and presents 10 arguments in favour of his assertion. The following appear to be the strongest three.

The holy Gāyatri mantra has 24 letters. The sage wrote Rāmāyaṇa text with 24,000 verses, using each consecutive letter of the mantra as the starting letter of each set of thousand verses. Removing Uttara Kāṇḍa makes the verse count of Rāmāyaṇa fall short of 24,000.

The ślōka 1.1.91 (Bāla Kāṇḍa) has the Sage Nārada describing Rāma Rājya as having the characteristic “na putramaraṇaṃ kiñcid drakṣyanti puruṣāh” (fathers shall not see the death of their sons), among others. This is substantiated by Uttara Kāṇḍa.

The ślōka 1.3.38 (Bāla Kāṇḍa) includes the phrase “vaidēhyāśca visarjanaṃ” (renunciation of Sīta), which seems to foretell the corresponding episode of Uttara Kāṇḍa.

Let us dissect the above arguments using textual evidence from other parts of the epic itself.

The Gāyatri Mantra Connection

Let us suppose, for the sake of argument, that Sage Vālmīki did compose the 24,000 verses of the epic poem keeping in mind the 24 letters of the Gāyatri mantra. It would be a feat of such proportions that it would deserve a mention or a claim somewhere. However, Sage Vālmīki never stated, nor hinted at, such a correlation – neither in the text nor elsewhere.

Besides, several scholars opine that numerous passages were grafted onto the main text of Rāmāyaṇa, over time. Culling them would render the epic with far fewer than 24,000 ślōkas. This alone would directly break the supposed correspondence between the number of verses in the epic and that of the letters in the Gāyatri mantra.

Description of Rāma Rājya

The ślōkas 1.1.90 to 1.1.97 of Bāla Kāṇḍa contain a brief description of Rāma Rājya, as narrated by Sage Nārada. In particular, the ślōkas 1.1.91 onwards are in future tense. A similar portrayal occurs towards the end of Yuddha Kāṇḍa in ślōkas 6.128.95 to 6.128.106. This passage invalidates the need for a separate kāṇḍa to repeat this description.

Vaasudaasa Swamy argues that the assertion in 1.1.91 (that fathers shall not see the death of their sons) anticipates the story of the death of a brahmin boy in Uttara Kāṇḍa sargas 73 through 76.

Ślōka 1.1.91 asserts that such an incident never occurs in Rāma Rājya. The actual occurrence of such a death, its getting traced to a purported violation of varṇavyavastha by Śambūka, and the resurrection of the dead boy through restoration of “dharma” raise more questions than they answer.

This episode comes across as a creative response to a changing social ethic that must have occurred centuries after Sage Vālmīki composed the original poem.

Implausibility of Mentioning the Renunciation of Sīta

Firstly, the ślōkas 1.3.10 through 1.3.38 retell the brief (saṅkṣēpa) Rāmāyaṇa that Sage Nārada recites in the ślōkas 1.1.19 to 1.1.89. They are attributed to Lord Brahma. Such retelling (punarukti) is considered a good quality (guṇa) in a lecture, but a poor one (dōṣa) in a written literary work. Attributing such a basic violation of the norm to Sage Vālmīki is an insult to his poetic genius.

Secondly, eliminating the said ślōkas 1.3.10-1.3.38 does not cause a discontinuity in the narrative! This lends significant strength to the hypothesis that they were a later addition.

Thirdly, the phrase “vaidēhyāśca visarjanaṃ” does not find room in Sage Nārada’s recitation of the brief Rāmāyaṇa, but somehow magically finds room in the much shorter repetition by Lord Brahma. Moreover, no other story from Uttara Kāṇḍa gets a mention in this repeated version. All the above clearly demonstrate that the ślōkas 1.3.10-1.3.38 were later additions, expressly invoked for bestowing legitimacy upon Uttara Kāṇḍa.

A Few Other Points to Ponder

In addition to the untenability of Vaasudaasa Swamy’s arguments, we come across several other points that indicate that Uttara Kāṇḍa was not a part of Sage Vālmīki’s original version of the epic.

Closure of the Storyline

Following the brief Rāmāyaṇa narrated by Sage Nārada, ślōka 1.4.1 (Bāla Kāṇḍa) says that the story of Rāma, who recovered his kingdom (“prāptarājyasya rāmasya”), was thus narrated beautifully and with a powerful message.

Similarly, the ślōka 1.4.7 states that Sage Vālmīki conceived three names for the epic: “rāmāyaṇaṃ” (the path of Rāma), “sītāyāścaritaṃ mahat” (the great story of Sīta) and “paulastya vadha” (the killing of Rāvaṇa).

In case a full kāṇḍa – that too something as big and heterogeneous as Uttara Kāṇḍa – was on its way after Yuddha Kāṇḍa, Sage Vālmīki would not have chosen the killing of Rāvaṇa as one of the titles of the epic. These titles would become incongruent with one another unless the storyline concluded with the crowning of Rāma.

How Many Kāṇḍas?

Ślōka 1.4.2 (Bāla Kāṇḍa) clearly says that Sage Vālmīki composed Rāmāyaṇa in 6 kāṇḍas (“ṣaṭ kāṇḍāni”). Furthermore, it says that the number of sargas is about 500 (“sarga śatān pañca”).

On the other hand, considering Uttara Kāṇḍa to be an integral part of Rāmāyaṇa would contradict the above: the number of kāṇḍas would become 7, while the number of sargas would come close to 650.

Phalaśruti

Any literary work of yore contains a small section, at the end, proclaiming the benefits of reading the work or listening to it (phalaśruti). This is a pattern which was adhered to very strictly.

Ślōkas 1.1.90 through 1.1.97 in Bāla Kāṇḍa describe Rāma Rājya. Immediately following that, we see that ślōkas 1.1.98 to 1.1.100 contain phalaśruti. Correspondingly, ślōkas 6.128.95 through 6.128.106 in Yuddha Kāṇḍa describe Rāma Rājya, which lasted for 10,000 years (“daśa varṣa sahasrāṇi rāmō rājyamakārayat”). Following it, ślōkas 6.128.107 to 6.128.125 establish phalaśruti in great detail.

Had Sage Vālmīki conceived Rāmāyaṇa as an epic of 7 kāṇḍas, he would never have provided a description of Rāma Rājya (in future tense), together with an elaborate phalaśruti right at the end of the 6th kāṇḍa itself, which is Yuddha Kāṇḍa.

Killing an Envoy

Uttara Kāṇḍa 13.39 states that an enraged Rāvaṇa killed the envoy sent by his cousin Kubēra (“dūtaṃ khaḍgēna jaghnivān”). This episode occurred back when Rāvana was waging his initial wars with the devatās.

Chronologically much later, in Sundara Kāṇḍa sarga 52, Vibhīṣaṇa advises against Rāvaṇa’s edict to kill Hanumān. In ślōka 5.52.15, he states that no one had ever heard of killing an envoy (“vadhaḥ tu dūtasya na naḥ śrutō api”). This incident occurred at the very threshold of the war, barely a month ahead of it.

The above two narratives directly contradict each other. Had the chronologically prior incident of Kubēra’s envoy really occurred, Vibhīṣaṇa would certainly have known of it. And, he would not have claimed that it was unheard of when Rāvaṇa ordered that Hanumān be killed.

The Story of Rāmāyaṇa in Mahābhārata

In Araṇya Parva of the epic Mahābhārata, Sage Mārkanḍēya narrates the story of Rāmāyaṇa to Dharmarāja in sargas 272 to 289. We see that a few of the elements of the story differ from the corresponding ones in Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa. Nonetheless, as per this narrative as well, the story of Rāmāyaṇa ends in sarga 289 with the crowning of Rāma. Clearly, the grafting of Uttara Kāṇḍa happened after Mahābhārata had been composed.

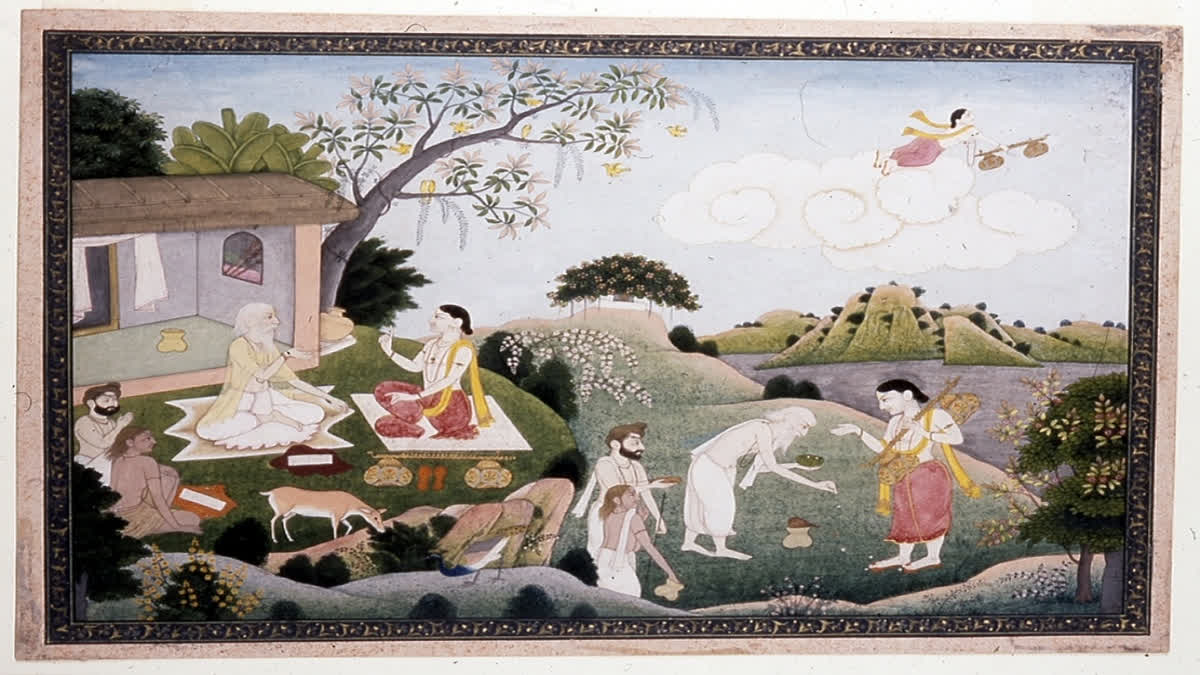

Lava and Kuśa Recite Rāmāyaṇa

According to Bāla Kāṇḍa ślōkas 1.4.27 through 1.4.29, Rāma came across the two ascetic boys Lava and Kuśa reciting Rāmāyaṇa in the streets of Ayodhya. He invited them to his palace and honoured them appropriately. Lava and Kuśa then recited Rāmāyaṇa in Rāma’s court.

On the other hand, Uttara Kāṇḍa sarga 94 states that Lava and Kuśa recited Rāmāyaṇa during a break in the rituals of aśvamēdha yāga (the horse sacrifice ritual) that Rāma was performing. And, the setting was the banks of the river Gōmati in Naimiśāraṇya. The settings contradict each other: only one of them can be valid.

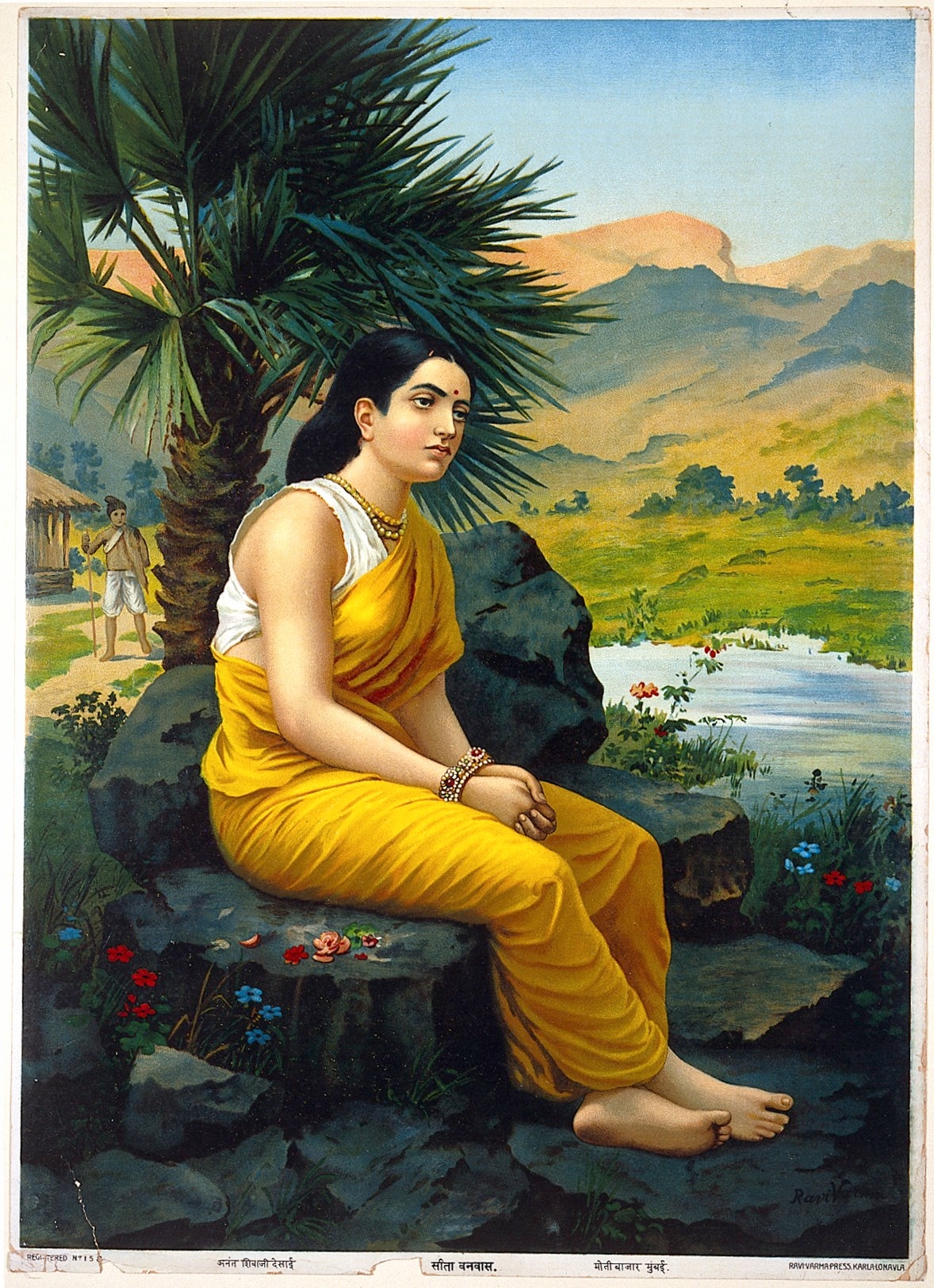

The Renunciation of Sīta

As per Uttara Kāṇḍa ślōka 42.29, Rāma and Sīta spent 10,000 years living together, enjoying the royal privileges: “daśavarṣa sahasrāṇi gatāni sumahātmanōḥ prāptayōrvividhān bhōgān”. Then, Sīta expresses her desire to spend some time with sages and ascetics in the forests. Thereupon, in sarga 43, Bhadra apprises Rāma about some men of Ayodhya lamenting Rāma’s acceptance of Sīta – who was detained by Rāvaṇa at his place for a year – since it was forcing them to treat their wives similarly.

It is ridiculous and hilarious to argue that the citizens of Ayodhya were in agreement with Rāma’s acceptance of Sīta for a full 10,000 years after their crowning, developing a discomfort in the matter only after that. To then argue that Rāma renunciated Sīta upon hearing their objections is plain character assassination. This is untenable as a logical argument.

Conclusion

We can, thus, conclude on solid grounds that Uttara Kāṇḍa was grafted on the epic Rāmāyaṇa much later, and certain additions were planted in – and modifications were made to – the main text of the epic, to lend credibility to the graft. Therefore, Uttara Kāṇḍa is not an integral part of the epic itself.