Economic inequality has been a significant issue in India, and it often serves as a point of debate in the political landscape. The political parties advocate for various economic policies that impact wealth distribution, and the discussion usually revolves around the balance between promoting economic growth and ensuring equitable distribution of wealth. Wealth inequality is a measure of the distribution of wealth in a country, and it is closely related to income inequality.

However, wealth inequality includes income and the value of savings, investments, stocks, and personal possessions such as jewellery. Wealth inequality is a significant cause of disparity in living standards and a hitch to an inclusive society.

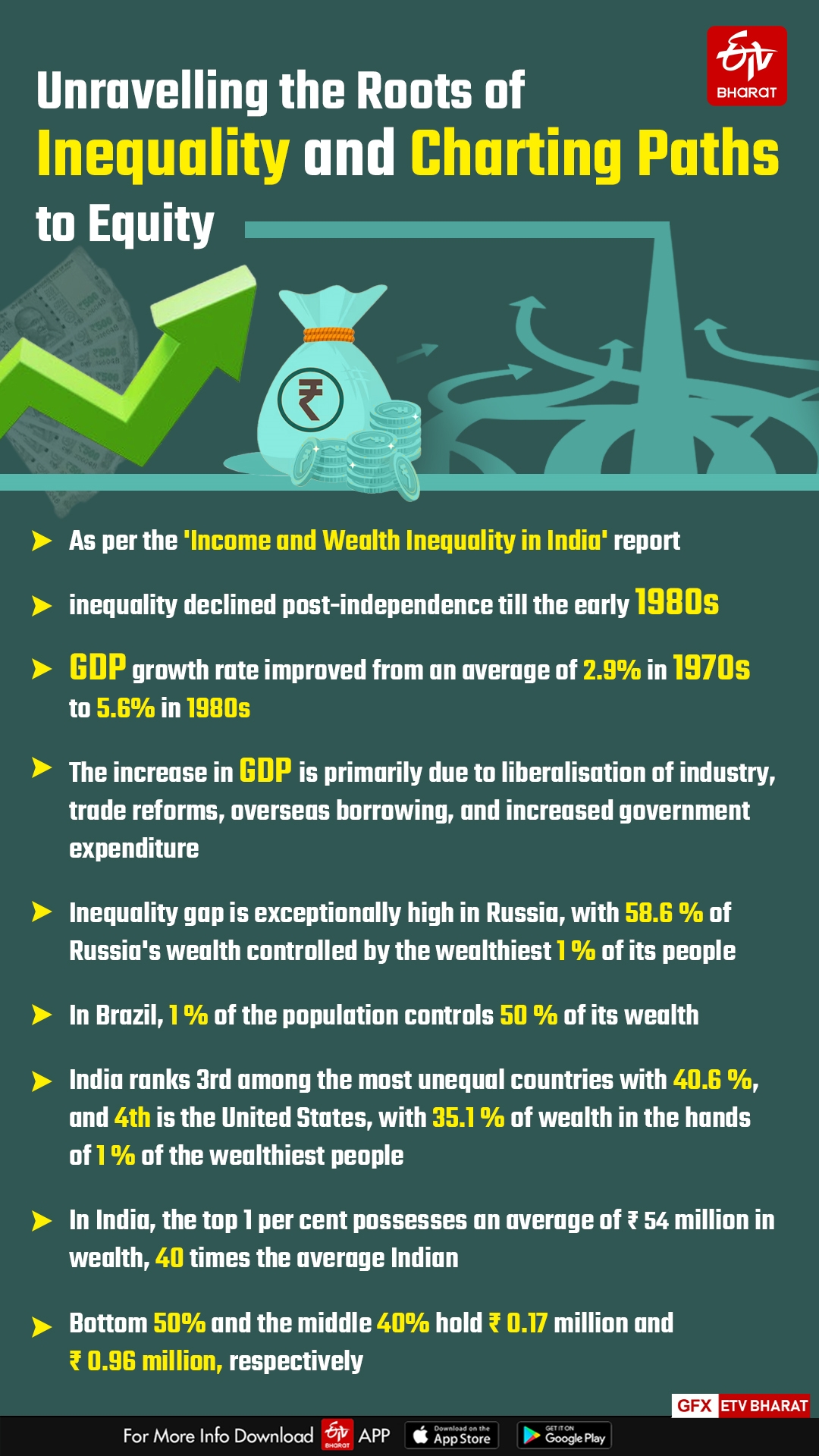

The World Inequality Lab's recent study on 'Income and Wealth Inequality in India', released in March 2024, sparked accusations and an agenda in political debates in ongoing Lok Sabha election campaigning. The report states that inequality declined post-independence till the early 1980s. On the contrary, the GDP growth rate improved from an average of 2.9 per cent in the 1970s to 5.6 per cent in the 1980s. The increase in GDP is primarily due to the liberalisation of industry, trade reforms, overseas borrowing, and increased government expenditure.

While economic reforms have contributed to India's economic growth, they are also associated with a significant increase in inequality. There is a strong belief that globalisation has reduced wealth inequality between nations but has increased wealth inequality within the nations. Developing nations are characterised by greater inequality compared to developed nations.

There are exceptions; the inequalities are generally high in some developed countries, such as Russia and the United States. If the gap between the wealthy and the poor widens, it can lead to social divisions. Economic inequality can fuel mistrust and resentment among different social and economic groups. Therefore, addressing this inequality while sustaining economic growth has been a critical challenge for policymakers in India.

Wealth Inequality: The inequality gap is exceptionally high in Russia, with 58.6 per cent of Russia's wealth controlled by the wealthiest one per cent of its people, followed by Brazil, where one per cent of the population controls 50 per cent of its wealth. India ranks 3rd among the most unequal countries, with 40.6 per cent, and 4th is the United States, with 35.1 per cent of wealth in the hands of 1 per cent of the wealthiest people.

The report highlights that, in India, the top 1 per cent possesses an average of ₹ 54 million in wealth, 40 times the average Indian. The bottom 50 per cent and the middle 40 per cent hold ₹ 0.17 million and ₹ 0.96 million, respectively. At the very top of the distribution, approximately 10,000 wealthiest individuals out of 920 million adults own an average of ₹ 22.6 billion in wealth, 16,763 times the average Indian.

Income Inequality: The share of national income that went to the top 10 per cent was 37 per cent in 1951, declining to 30 per cent by 1982. From the early 1990s onwards, the top 10 per cent share increased significantly over the next 30 years, almost 60 per cent in recent years. On the contrary, the bottom 50 per cent were getting only 15 per cent of India's national income in 2022-23. One of the primary reasons for this disparity in income levels is the lack of broad-based education for the masses with low income. To illustrate how skewed the income distribution is, one would have to be at the 90th percentile to earn the average income in India, which means only one in ten can earn an average income in India.

Covid and Inequality: The pandemic has worsened the existing inequalities in the labour market, primarily because working remotely is highly related to education. While there's been much emphasis on "essential workers" and the notion of unity, the harsh truth remains: lower-skilled and uneducated workers likely bore the brunt of job and income losses. The International Monetary Fund, in its report, argued that households with more youth or children headed by less educated individuals faced severe incidences of becoming poor and significant loss of income during the pandemic. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased poverty and inequality; though the impact was temporary, poverty and inequality returned to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2021.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a peculiar phenomenon unfolded in the Indian capital markets, notably exacerbating inequality during this crisis. The pandemic and frequent lockdowns adversely affected economic growth. Despite this turmoil, the major stock indices exhibited volatility before embarking on a bullish trajectory, almost as if the Indian stock market remained impervious to unforeseen events. For instance, on March 24, 2020, the BSE Sensex plummeted to a yearly low of 25,638, shedding 16,635 points in 46 trading days.

Astonishingly, following this crash, within 226 trading days, the BSE Sensex surged to its all-time high (during the pandemic) of 52,516 points, reclaiming nearly 26,878 points.

Tackling Inequalities: India is one of the major economies in the world with higher growth rates, but the unfortunate and contending issue is the growing inequalities in society. To tackle the deepening disparities, the government should focus on Income Before Taxes and Income After Taxes, i.e. gross earnings and disposable income of individuals, to deal with inequalities. The policies aimed to narrow the differences between the gross income levels of individuals by creating employment opportunities through quality education, thus ensuring an equal level playing field for all. Government intervention through taxes and social transfers would help individuals cope with various adverse events such as unemployment, ageing, family expansion, disability, or sickness.

Significant disparities exist between higher and lower-income households regarding access to education, health care, and housing. These inequalities put the budding children in unequal starting positions. To tackle the above, government spending on education, health care and housing would reduce the gap between the rich and poor. The other measures include ensuring access to basic public infrastructure such as clean water and sanitation, primary health care services and social investments such as education.

Taxing the Rich: Though taxing the rich is not new in India, the government has done this to ensure that the rich contribute to the income taxes more than the poor, owing to the surcharge provision. The World Inequality Report further suggested that by charging a 'super tax' of merely 2 per cent on 167 of the wealthiest families in India, the financial year 2022-23 could generate a significant 0.5 per cent of national income in revenue, enabling the fiscal support to investments in the social sector.

India in the late 1940s was a highly unequal society. Therefore, to reduce the inequalities, estate taxes were introduced in 1953, and wealth taxes were introduced in 1957. However, these taxes were withdrawn in 1985 and 2016, respectively. The reasons for their withdrawal were that the gross tax revenue was less than 0.25 per cent compared to the high administration and compliance costs. Also, it was argued that. The concurrent taxes on wealth and estate amounted to double taxation.

Recently, there have been debates within certain quarters, including political parties and economists, about reintroducing inheritance tax in India. However, the Union Finance Minister said India's progress in the last ten years will be 'zero' if the inheritance tax is implemented. On the other hand, on March 11, 2024, the United States proposed taxation of the wealthiest Americans in its budget proposal. Taking clues from the United States, Sam Pitroda, a U.S.-based entrepreneur, suggested introducing an inheritance tax in India, which sparked debates in India.

(Disclaimer: The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the organisation he is affiliated with)