In Indian politics, defections remain the flavour of all seasons. Most recently, 3 independent MLAs withdrew support from the Nayab Singh Saini-led BJP government in Haryana, and announced their intention to campaign for the Congress. Haryana is hardly a stranger to defections, having birthed the adage 'Aya Ram, Gaya Ram' to refer to unprincipled floor-crossing. Simultaneously, with Lok Sabha elections underway, many other states (such as Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat) have witnessed last-minute movements of candidates across parties.

While political defections abound, India's anti-defection law remains a silent spectator. Housed under the Tenth Schedule of the Constitution of India, the anti-defection law was enacted in 1985 to curb rampant floor-crossing by elected legislators in the 1960s-70s, both in Parliament and state Assemblies. In 2002, however, the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution scathingly indicted the law by pointing out that India witnessed a higher number of defections after the coming into force of the anti-defection law! How did the Tenth Schedule lose the plot so miserably?

What does the law punish and what remains exempted?

Many of the shortcomings of the Tenth Schedule can be attributed to its drafting, which leaves glaring loopholes for defections to pass through, especially group defections. The Tenth Schedule disqualifies legislators who voluntarily abandon the membership of their party or when they vote against their party's direction in the Parliament or state assembly. Independent MPs/MLAs are liable to be disqualified from the House if they join any political party after their election. Petitions for disqualification lie before either the Speaker or Chairperson of the House, as the case may be.

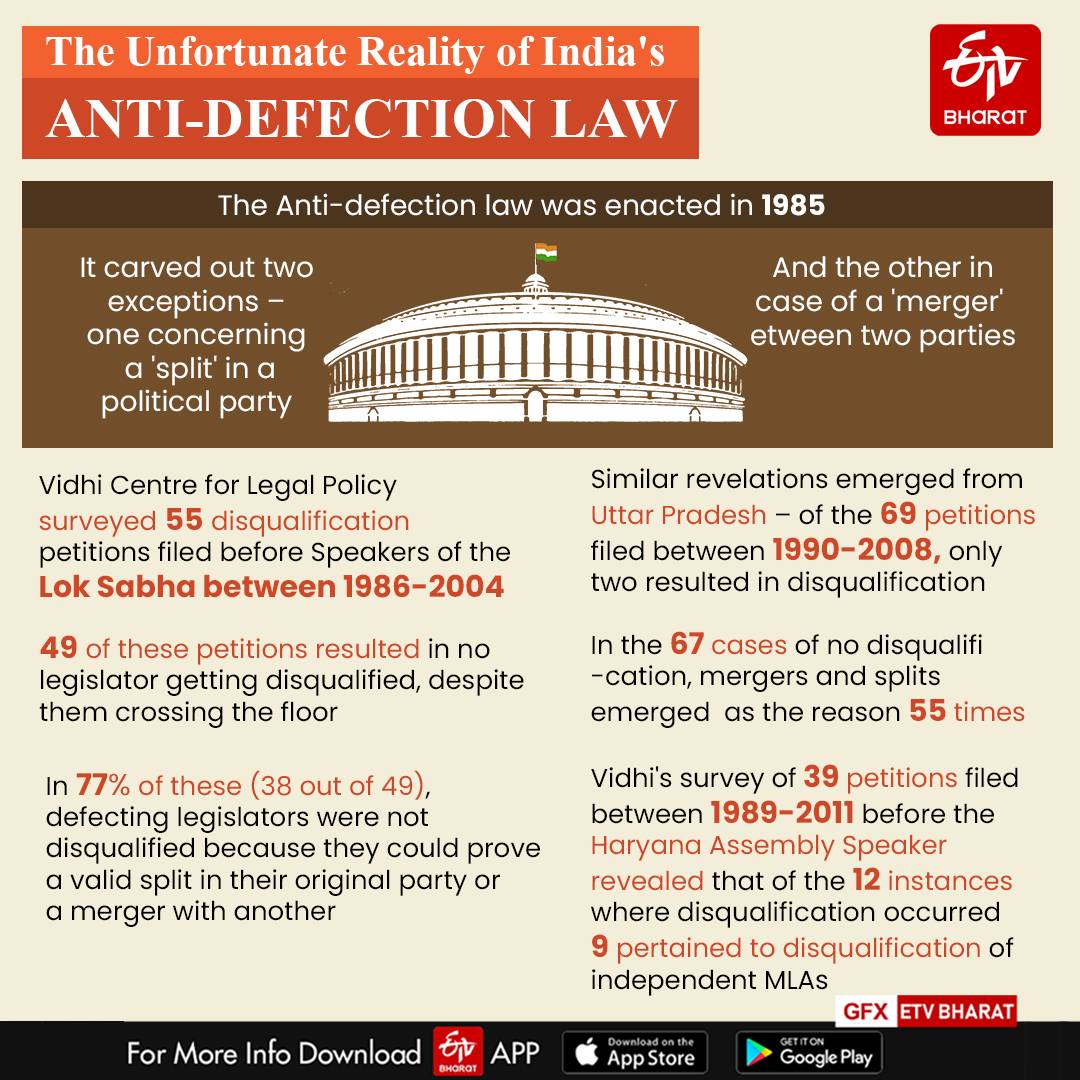

The anti-defection law also carved out two exceptions – one concerning a "split" in a political party, and the other in case of a "merger" between two parties. Parliamentary debates around this law reveal that these exceptions were to be used sparingly to protect principled instances of defections prompted by ideological differences between legislators and their parties. While the intentions were noble, these exceptions were used far too often for anyone's comfort. In fact, because of its repeated use to engineer defections and topple democratically elected governments, the split exception was deleted from the Constitution in 2003.

The merger exception has, however, stayed on. Found under Paragraph 4 of the Tenth Schedule, the merger exception spans across two sub-paragraphs. A combined reading of these two sub-paragraphs mandates that a legislator can claim exemption from disqualification if two conditions are fulfilled simultaneously - first, the legislator's original political party merges with another political party, and second, the legislator is part of a group that comprises two-third members of the "legislature party" that agrees to the merger. A legislature party means the group consisting of all elected members within a legislative House belonging to one particular party.

A cursory glance at the merger exception reveals its needlessly complicated drafting which lends itself to multiple interpretations by both Speakers as well as courts. The interpretation which has found favour by several High Courts is that as soon as two-thirds of a particular legislature party agrees to merge with another legislature party, a merger between two political parties is "deemed" to have taken place. Such an interpretation does not require a factual merger of the original political parties at the national or regional level.

How does the merger exception enable 'group/bulk defections'?

This seemingly convoluted legalese has a distinctly tangible impact on the actions of political parties, both within and outside legislatures. Given that parties only need to show a merger between their legislative wings inside the House (and not of members outside it), valid mergers are comfortably pulled off. A telling example of this is when in 2019, 10 out of 15 Congress MLAs in the Goa Legislative Assembly joined the BJP, and this was held to be a valid merger between the BJP and INC legislature parties. The 10 INC MLAs were exempted from disqualification by the Goa Assembly Speaker whose decision was eventually upheld by the Bombay High Court (Goa bench). Effectively, the need to prove only deemed mergers between legislature parties has practically eased group defections.

Quite naturally, mergers and splits have been the primary cause for defecting legislators not getting disqualified under the anti-defection law. The Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy ('Vidhi') conducted a survey of 55 disqualification petitions filed before Speakers of the Lok Sabha between 1986-2004. 49 of these petitions resulted in no legislator getting disqualified, despite them crossing the floor.

In 77% of these (38 out of 49), defecting legislators were not disqualified because they could prove a valid split in their original party or a merger with another. Similar revelations emerged from Uttar Pradesh – of the 69 petitions filed between 1990-2008, only two resulted in disqualification. In the 67 cases of no disqualification, mergers and splits emerged as the reason 55 times (nearly 82%).

Has the anti-defection law done any good?

The anti-defection law has had some success in punishing defections by individuals, including independent MPs/MLAs. Vidhi's survey of 39 petitions filed between 1989-2011 before the Haryana Assembly Speaker revealed that of the 12 instances where disqualification occurred, 9 pertained to disqualification of independent MLAs. This included the disqualification in 2004 of 6 independent MLAs, who joined the Congress ahead of the Rajya Sabha elections, by Speaker Satbir Singh Kadian.

Of the 18 disqualification petitions surveyed from the Meghalaya Assembly (1988-2009), five concerned independent MLAs who were disqualified by the Speaker for joining a political party. Three such instances occurred in quick succession between 8-9 April 2009, when independent MLAs Paul Lyngdoh, Ismail R. Marak, and Limison D. Sangma joined the Congress, United Democratic Party, and the NCP, respectively. All of them were disqualified by the then Speaker Bindo M. Lanong who also chided independent MLAs for mocking the democratic system by siding with political parties of their choice once elections were over.

Is there a future for the Tenth Schedule?

Data around Speaker decisions from across state assemblies is not readily available on their official websites (at least not in English), which can preclude a comprehensive evaluation of the Tenth Schedule. Nonetheless, it is safe to say that the law's successes have been numbered, and it remains largely unworkable. Earlier this year, at the All India Presiding Officers’ Conference, a committee was constituted for review of this law. One can only hope that this committee does the needful – undertake a comprehensive review of the Tenth Schedule's performance, and give India an anti-defection law which furthers parliamentary democracy.

(The writer works at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, New Delhi where she leads Charkha, Vidhi's dedicated constitutional law team. Her current research covers themes under parliamentary democracy, delimitation of electoral constituencies, and electoral reform)