This year’s UN-led Climate Summit, COP 29 (the 29th Conference of Parties), kicked off in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, on November 11 and runs through the 22nd of this month. Attended by the representatives of 200 countries, this conference will review the progress in reducing greenhouse gas emissions against each country’s declared targets for limiting global warming. Most importantly, the meeting will discuss climate finance and its modalities.

"The emissions gap is not an abstract notion," said António Guterres, UN Secretary-General, in a video message on the report. "There is a direct link between increasing emissions and increasingly frequent and intense climate disasters … Record emissions mean record sea temperatures supercharging monster hurricanes; record heat is turning forests into tinderboxes and cities into saunas; record rains are resulting in biblical floods … We’re out of time. Closing the emissions gap means closing the ambition gap, the implementation gap, and the finance gap. Starting at COP29."

The fact that the leaders of the most populous countries, India and China, are not attending the meeting hardly augurs well. One of the most notable leaders in attendance is the U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who announced an 81% emissions reduction target on 1990 levels by 2035. This promise is in line with the Paris Agreement goal to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial times.

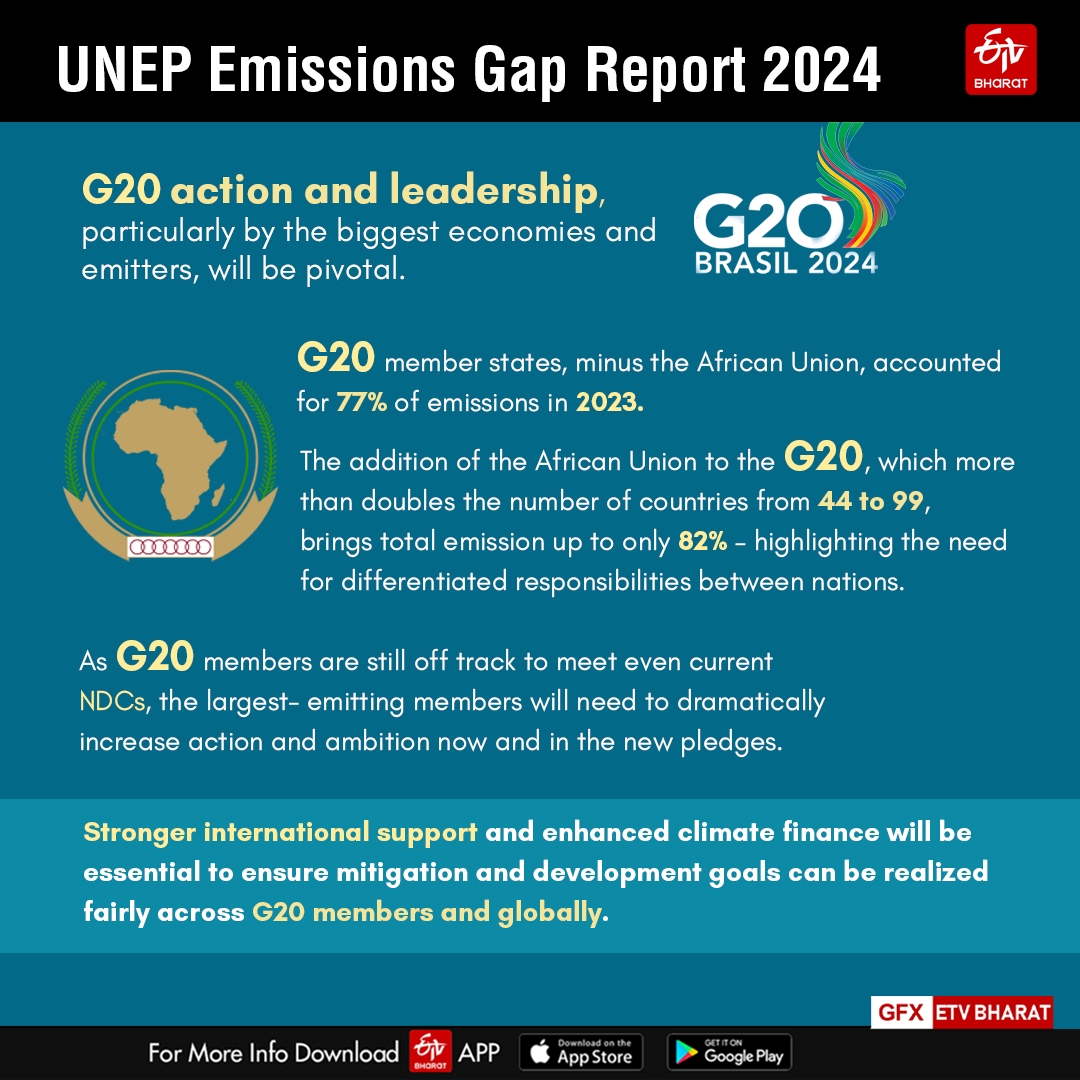

The endless contention will also repeat in Baku on how responsibility is shared between the countries and which countries will shoulder the major share of finance that foot the climate bill to help the poorer countries shift to a low-carbon economy. Nations negotiate huge amounts, anywhere from $100 billion to $1.3 trillion annually.

It is reported that the G77 and China negotiating bloc — which includes many of the world's developing countries — put forward a unified demand of $1.3 trillion annual climate finance for the first time. It is also reported that countries like India would be canvassing for climate financing by the developed countries and maintaining standards for a global carbon trading mechanism.

The first UN-sanctioned carbon credits are expected to be available by 2025. Many innovative ways of raising climate finance are discussed as global inequality soars – like levies on high-carbon activities, from private jets to gas extraction. Other suggested targets of tax levies are the oil companies that made huge profits after Russia invaded Ukraine. How practical they are and how they can be implemented are the questions that are also being raised. Another area of contention is the nature of regulatory mechanisms for carbon credits and offsets. Many think this is utopian, and the theoretical elegance of the concept does not match real-world special interests.

It is worth mentioning here that a group of world leaders led by Gordon Brown, the former UK prime minister, wrote an open letter making a case for loosening the purse strings of petrostates and asking for a minimum of $25 billion levy on them. Suggestions include reforming the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and other developmental banks to prepare them to help vulnerable countries. Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has proposed a billionaire tax of 2% that could raise $250 billion. The next COP will convene in November 2025 in Belém, Brazil and hopefully, that will offer a platform to discuss such measures and reach an agreement.

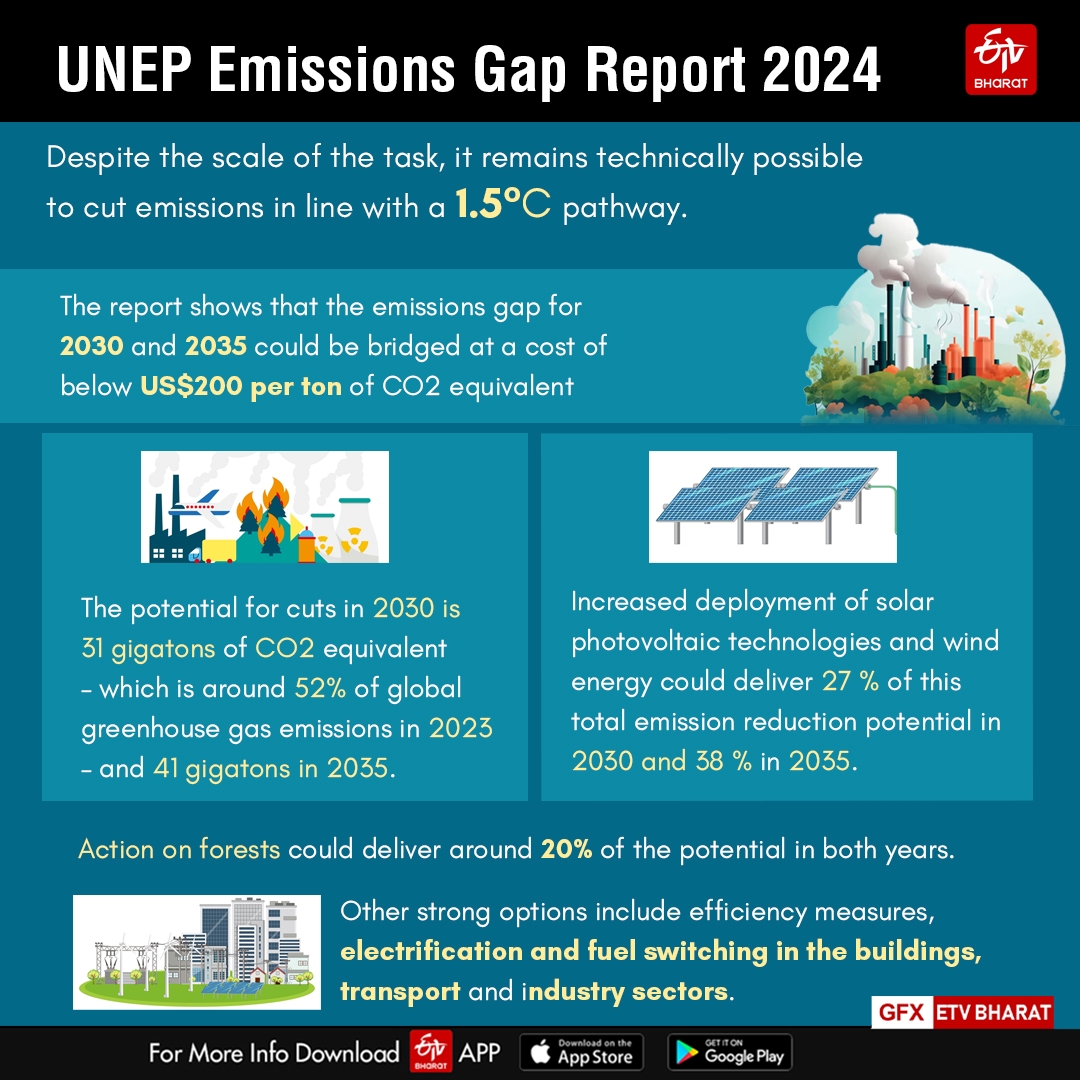

Although the emissions from 42 countries, including the United States, China, Russia and the European Union, show a decline, in 2023, global emissions reached a record high of 37.4 billion tons of carbon dioxide by burning fossil fuels, the primary driver of global change. This is mostly due to the increased dependency on coal as the primary energy source. Unless drastic emission reduction plans are implemented in the next few years, as a recent UN Environment Programme (UNEP) report warns, the current policies will lead to a catastrophic temperature rise of 3.1 degrees Celsius.

The report asks nations to "collectively commit to cutting 42 per cent off annual greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and 57 per cent by 2035 in the next round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)". If they don’t stick to this plan, the UN report warns that the "Paris Agreement's 1.5°C goal will be gone within a few years … "that would bring debilitating impacts to people, planet and economies."

This year’s COP is meeting under the shadow of the election victory of Donald Trump, a self-declared climate change denier, as the President of the United States, a leading polluter among the nations, has stated that he would exit the Paris Climate Agreement signed in 2016, as he did in his previous presidency.

The American conservative think tank the 'Heritage Foundation' in their document 'Project 2025' also calls for the US to withdraw from the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement. The reports indicate that the incoming administration under the Trump presidency is drawing up plans to boost oil and gas drilling and undercut the outgoing president Joe Biden's massive investments in strengthening alternate non-conventional energy sources.

Trump’s rollbacks could release an additional carbon dioxide emission of 4 billion tons to the atmosphere by 2030, compared with Biden’s plans. Following Trump’s policy of incentivising the conventional energy industry, the US’s target under the Paris Agreement to achieve a 50-52% reduction by 2030 will fall by the wayside. A possible US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement will also further burden the other rich countries on financial responsibility.

The UN report says there is still a technical possibility of reaching an emission cutoff cap of 31 gigatons in 2030 – around 52 per cent of emissions in 2023. This would bridge the gap to 1.5°C at a cost below US $200 per ton of CO2 equivalent. Increased renewable energy capacity by expanding solar photovoltaic technology and wind energy, restoration of forests and other ecosystems, and electrification in transport and industry sectors by transitioning away from fossil fuel offers us the potential to attain those targets.

The meeting venue – Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, which exports vast quantities of fossil fuels has attracted ridicule from climate activists. Greta Thunberg, a globally prominent climate activist, has already raised the question of how an authoritarian petrostate like Azerbaijan, in war with the neighbouring country Armenia, can host a climate conference. She says while humanitarian crises are unfolding in various parts of the world, humanity is also breaching the 1.5C greenhouse gas emissions limit, with no signs of real reduction. She says the climate crisis is as much about protecting human rights as about protecting the climate and biodiversity.

The gathering in Baku is smaller than many previous summits. Unlike the earlier summits, the top leaders of the 13 largest carbon dioxide-polluting countries, including the United States, France and Germany, will not attend this meeting. The nations unrepresented by their top leaders cause more than 70% of 2023's greenhouse gases. The election of a climate-change denialist as the US president has dampened the global enthusiasm, which will also be reflected in COP 29.

(Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer. The facts and opinions expressed here do not reflect the views of ETV Bharat)