By Khalid Bashir Gura

There is no terror, terrorist, terrorism, tourism, or tourists. There is no paradise. No vast white landscape of snow or shrouds. No boats bobbing in the placid lake. No crowd running away from forever chasing bullets, and bombs. No bullet-ridden piles of body bags. There are no collaborators, no wars. No enemies of nations. There is no conflict. Yet there is ordinary, everyday Kashmir where hearts break and ache in silent screams.

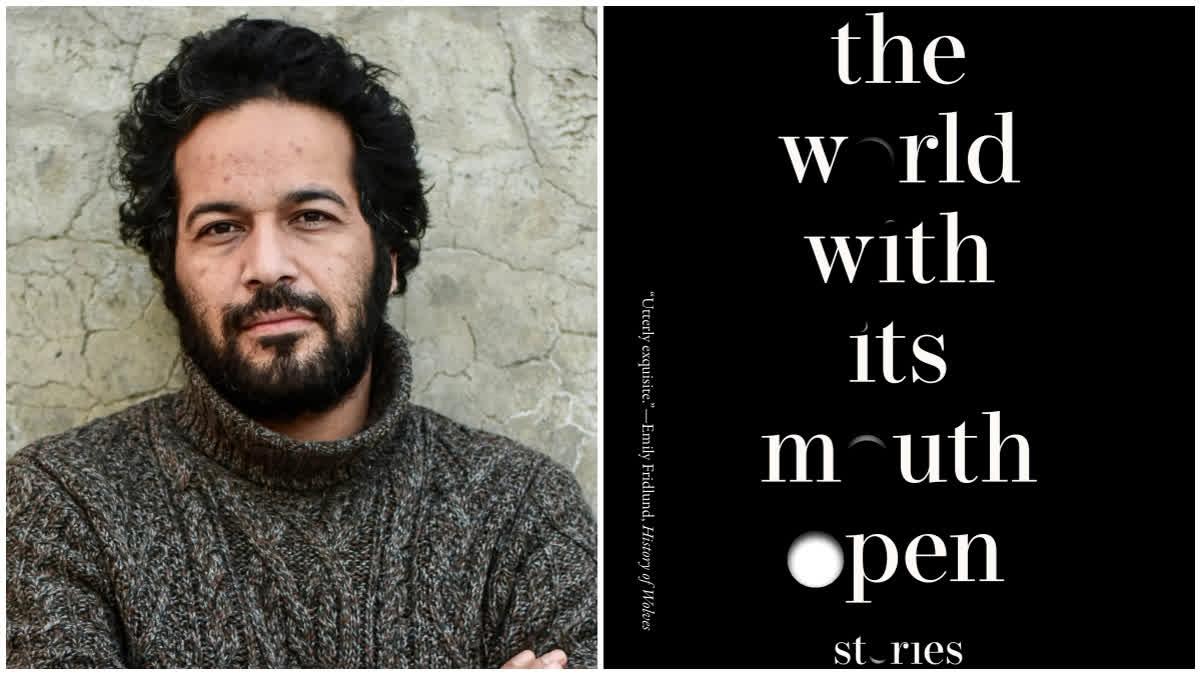

As one unspools the stories of Zahid Rafiq’s debut collection of stories, The World With Its Mouth Open, the everyday lives of Kashmiris, often overshadowed by narratives and noise of conflict speak in snapshots. Zahid, who now lives in Kashmir's Srinagar, was a journalist for several years before turning to writing fiction.

Zahid weaves his stories around ordinary Kashmir minus the cliche the rest of the world associates with the place. On the face of them, the stories aren’t about the political conflict. A single read tells you how Zahid has taken a new path to Kashmir. But read the book a second time and one wonders if it too can be read on different levels.

Zahid’s characters are those we have known for a very long time but have never chosen to sit and converse in the humdrum of life. His stories give life to those muffled screams and silent struggles in the neighbourhood.

The characters, the names, and the places exhibit the frame we inhabit in real life. We can only see the picture in the frame if we walk out. And The World With Its Mouth Open does that. The book was released in December 2024 by Tin House in the USA.

The stories without gratifying endings hold one's hand and make one listen, shudder and surprise but what? How? Where? There is grief, loss, hope, humour, sarcasm, silence, mourning, resilience, and survival as varied themes run in the background.

Set in Kashmir, the stories have the disillusionment entailing miscarriages of hope, surmounting societal expectations, daily financial crisis, battling indomitable fate, uncertainty and disappearance of past and present.

There is a teacher inducing terror through corporal punishment to convey to his students that there is The World With Its Mouth Open. He, however, is battling his own defeat and attrition at the hands of fate. Fate wedged him in what we wanted to be and what he is. Similarly, the ‘delinquent, incorrigible boy’, takes refuge in his silence. He wonders about birds in the borderless sky.

Another story reflects how in a land of obituaries, a mistaken obituary or news changes the life of a person who is induced with paranoia. Shaped by the years of conflict, this paranoia has also seeped into the general population.

There are stories which reflect the consequences of conflict in grief-stricken families, and how the living carry the dead within the deep recess of their lives.

There is a lover who grieves the loss of his beloved as he searches for her grave. There is an ominous presence of the discovery of the human hand near the construction site of a house. It, in itself, makes owners fret about the future prospect and its impact.

There is a frustrated unemployed youth wedged between familial expectations and job rejections. A worrywart mother’s everyday evening waits after losing her one son to government forces bullets. There is a mannequin which unsettles and obsesses the shopkeeper. He is secretly consumed by the uncertainties in business and entailing stress even at home. His wife complains to him of being indifferent as he is wedged between wife and mother. The home is also a battleground.

Zahid has meticulously narrated the story as it hinges on other strong characters reflecting the socio-political milieu of society. Even the curses and abuses come from everyday lingo.

In his last story, he adopts a sarcastic tone in a monologue and questions the conscience of society. He labels present-day doctors as “kidney thieves”. He delves into the state of journalism which conveys no news but ironically the advertisements inform about the new pimps in town, new sellers and buyers as he goes on explaining everyday ordinary stories.

As the author belongs to the land and language there is rarely any gap in the thoughts and words. The stories seem less a product of imagination and more of lived experiences. The language is laced with Kashmiri thoughts and at times it feels the author is narrating Kashmiri stories in English which only Kashmiris can understand. Phrases like “fat has grown on their eyes”, and “Did the butterhead ask you to leave?” are neither about the fat nor butter.

Laced with ground realities beyond clichés, the stories are as fresh as the whiff of spring breeze. However, still, the characters have a life of their own. The resilient characters have evolved to accept the haunting realities of the present. They rise above being victims of circumstance but emerge as individuals with their dreams, desires, convictions, contradictions and what late Indian psychoanalyst, Sudhir Kakar would call: Inner World!

At times, it feels like the characters have no bigger battles to surmount as living each day in itself and within oneself is a battle. Their life is as life is: constant struggle; within and outside. Zahid’s prose is vivid, economical and poetical like the seasons of the land. Each story has hope and hopelessness, grief and joy, humour and pathos running parallel like two banks of a silent river.

Zahid offers a fresh and intimate glimpse of an ordinary, everyday silent struggle of life in Kashmir. The stories are repositories of metaphors and proverbs. He connects present with past, past with future, delves into the beliefs, faith and psyche of commoners, digs into the grave of memories, expresses sexual fantasies of frustrated youth, and describes concerns, worries, and issues that plague everyday life.

Zahid’s description of intimate moments between a man and his wife is a daring attempt that reflects the veiled aspects of Kashmiri society, of how a stressed man becomes self-centred and aversive to any banal conversation in the bed once his sexual desire is fulfilled.

The author delves into sexual and everyday psyche and portrays how after a stressful day, a man seeks solace in intimacy in the dark hour of the night with his wife. However, despite his daily struggles with livelihood in uncertain regions, he has household attritions and cribbing to attend. Similarly, a woman who has to conform to societal norms has her share of household frustrations piled up and seeks a compassionate ear to listen before lovemaking. She also knows how and what can make a man listen and affirm to her even if pretentiously and tentatively.

These are the ordinary conversations in ordinary stories. The author has entered the lives of characters in the middle of the happening as there is no start or perfect end. There is an ambiguity.

Life goes on as there are no constructed endings of any emotional texture; joy or sorrow. The author leaves the stories midway and leaves the interpretation to the imagination. The book is a refreshing departure from earlier themes of conflict.

Zahid’s journalistic skills of seeing, listening, observing and letting other people speak their lives have not let his readers down. The book is unputdownable, however, its elusive endings and some mysterious characters and plots create discomfort for readers used to consistency and gratified narratives.