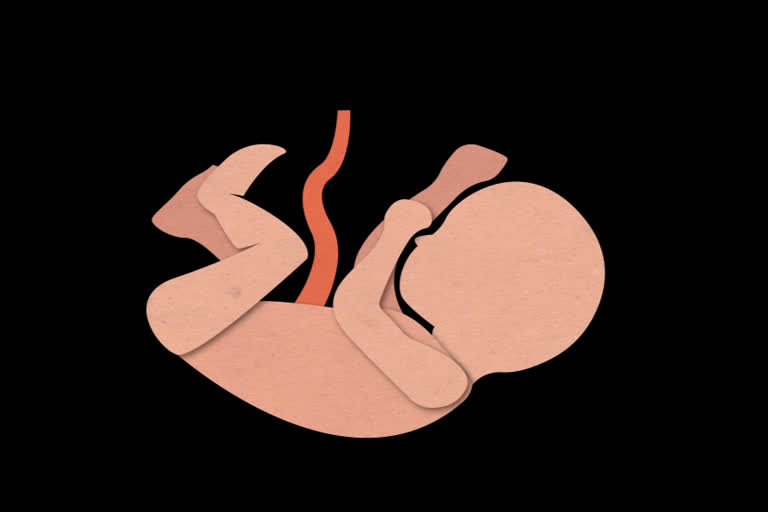

The study, reported in the medical journal Placenta, showed that inhaled nanoparticles - human-made specks that can't be seen in conventional microscopes, found in thousands of common products - can cross the natural, protective barrier that normally protects fetuses. The resulting inflammation may affect bodily systems, such as blood flow in the uterus, which could inhibit the growth of the foetus.

Rutgers University scientists studying factors that produce low-birth-weight babies revealed that they were able to track the movement of nanoparticles made of metal titanium dioxide through the bodies of pregnant rats. After the nanoparticles were inhaled into the lungs of the rodents, some of them escaped this initial barrier. From there, the particles flowed through the placentas, which generally filter out foreign substances to protect the foetus.

"The particles are small and really hard to find," said Phoebe Stapleton, Assistant Professor at Rutgers. "But, using some specialised techniques, we found evidence that the particles can migrate from the lung to the placenta and possibly the fetal tissues after maternal exposure throughout pregnancy. The placenta does not act as a barrier to these particles. Nor do the lungs," Stapleton added.