Lancaster (UK):We are constantly reminded about how exercise benefits our bone and muscle health or reduces fat. However, there is also a growing interest in one element of our anatomy that is often overlooked: our fascia.

Fascia is a thin casing of connective tissue, mainly made of collagen a rope-like structure that provides strength and protection to many areas of the body. It surrounds and holds every organ, blood vessel, bone, nerve fibre and muscle in place. And scientists increasingly recognise its importance in muscle and bone health.

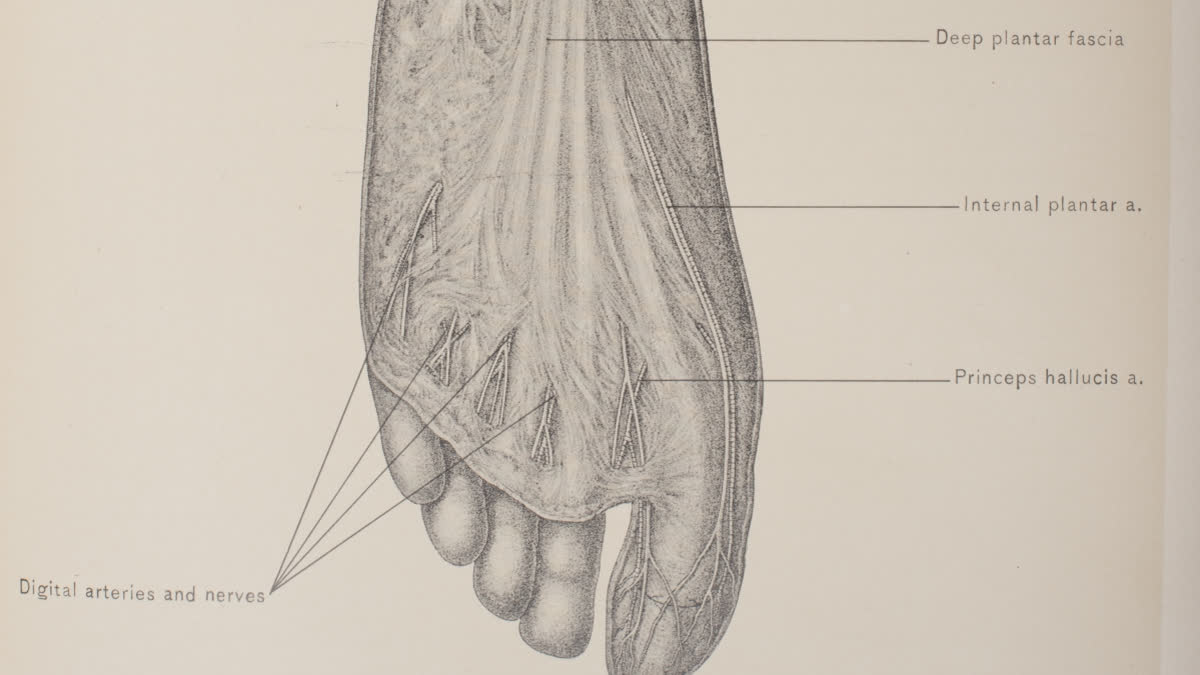

It is hard to see fascia in the body, but you can get a sense of what it looks like if you look at a steak. It is the thin white streaks on the surface or between layers of the meat. Fascia provides general and special functions in the body, and is arranged in several ways. The closest to the surface is the superficial fascia, which is underneath the skin between layers of fat. Then we have the deep fascia that covers the muscles, bones and blood vessels.

The link between fascia, muscle and bone health and function is reinforced by recent studies that show the important role fascia has in helping the muscles work, by assisting the contraction of the muscle cells to generate force and affecting muscle stiffness. Each muscle is wrapped in fascia. These layers are important as they enable muscles that sit next to, or on top of, each other to move freely without affecting each other's functions.

Fascia also assists in the transition of force through the musculoskeletal system. An example of this is our ankle, where the achilles tendon transfers force into the plantar fascia. This sees forces moving vertically down through the achilles and then transferred horizontally into the bottom of the foot - the plantar fascia when moving.

Similar force transition is seen from muscles in the chest running down through to groups of muscles in the forearm. There are similar fascia connective chains through other areas of the body.

When fascia gets damaged

When fascia doesn't function properly, such as after injury, the layers become less able to facilitate movement over each other or help transfer force. Injury to fascia takes a long time to repair, probably because it possesses similar cells to tendons (fibroblasts), and has a limited blood supply.

Recently, fascia, particularly the layers close to the surface, have been shown to have the second-highest number of nerves after the skin. The fascial linings of muscles have also been linked to pain from surgery to musculoskeletal injuries from sports, exercise and ageing. Up to 30% of people with musculoskeletal pain may have fascial involvement or fascia may be the cause.

A type of massage called fascial manipulation, developed by Italian physiotherapist Luigi Stecco in the 1980s, has been shown to improve the pain from patellar tendinopathy (pain in the tendon below the kneecap), both in the short and long term. Fascial manipulation has also shown positive results in treating chronic shoulder pain.