European and American health authorities have identified a number of cases monkeypox in recent days, mostly in young men. It's a surprising outbreak of disease that rarely appears outside Africa. Health officials around the world are keeping watch for more cases because, for the first time, the disease appears to be spreading among people who didn't travel to Africa. They stress, however, that the risk to the general population is low.

What is monkeypox?

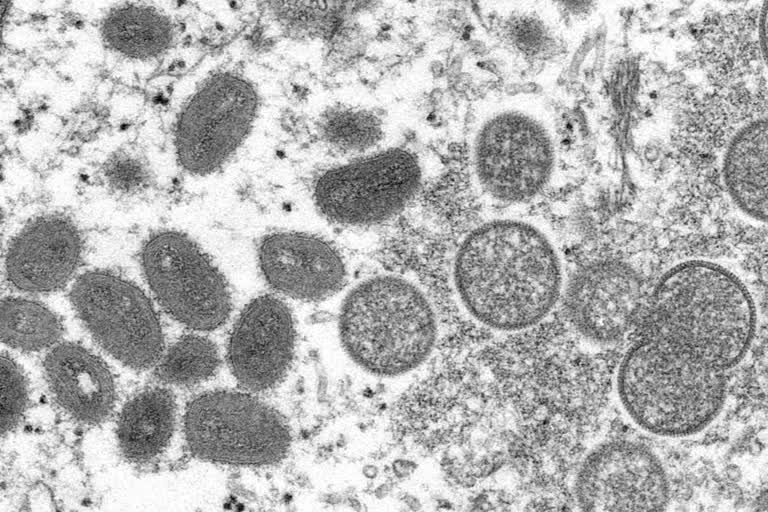

Monkeypox is a virus that originates in wild animals like rodents and primates and occasionally jumps to people. Most human cases have been in central and west Africa, where the disease is endemic. The illness was first identified by scientists in 1958 when there were two outbreaks of a pox-like disease in research monkeys thus the name monkeypox. The first known human infection was in 1970, in a 9-year-old boy in a remote part of Congo.

What are the symptoms and how is it treated?

Monkeypox belongs to the same virus family as smallpox but causes milder symptoms. Most patients only experience fever, body aches, chills and fatigue. People with more serious illness may develop a rash and lesions on the face and hands that can spread to other parts of the body. The incubation period is from about five days to three weeks. Most people recover within about two to four weeks without needing to be hospitalized. Monkeypox can be fatal for up to one in 10 people and is thought to be more severe in children.

People exposed to the virus are often given one of several smallpox vaccines, which have been shown to be effective against monkeypox. Anti-viral drugs are also being developed. On Thursday, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control recommended all suspected cases be isolated and that high-risk contacts be offered the smallpox vaccine.

How many monkeypox cases are there typically?

The World Health Organization estimates there are thousands of monkeypox infections in about a dozen African countries every year. Most are in Congo, which reports about 6,000 cases annually, and Nigeria, with about 3,000 cases a year. Patchy health monitoring systems mean many infected people are likely missed, experts say.