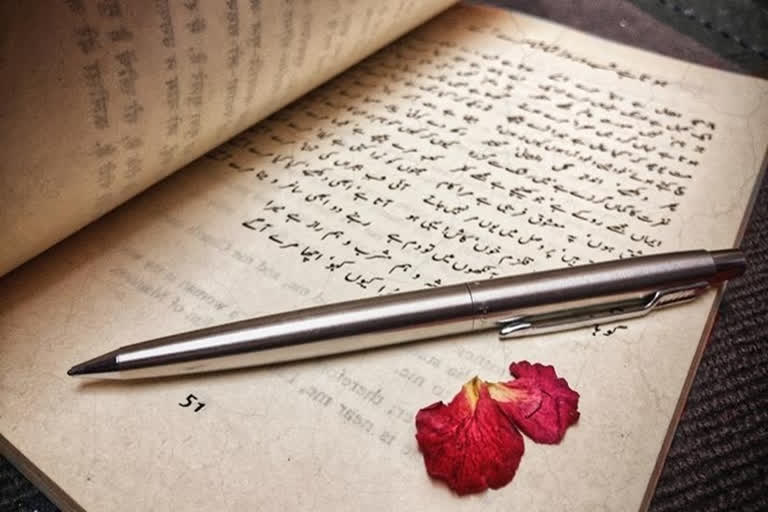

New Delhi: The occasion, when Urdu journalism is celebrating 200 years of its existence, seems to be perhaps the best opportunity to clear some myths and misconceptions about Urdu. Urdu is a language, which was born and flourished in India. However, unfortunately following in the footsteps of the colonial masters, the new rulers of India too, demarcated languages on the basis of religion. Though in reality, no language needs any religion to flourish but religions need a language to flourish.

In Urdu's case, nothing can be far from the truth. It was a language, which was patronised by all sections of the society, irrespective of their religion. But petty mindedness clubbed it together with a particular community. The colonial masters ascribed Hindi to Hindus and Urdu to Muslims, though both languages possess a rich tradition of substantial contributions from both sides.

It would be pertinent to note that in Urdu litterateurs consider Malik Ram to be an authority on Ghalib and similarly Jagan Nath Azad on the life, philosophy and works of Muhammad Iqbal, the two great poets of Urdu. On the occasion of 200-years of Urdu journalism in India, let's try to see how various Indians irrespective of their religion, enriched the language.

Urdu journalism, the language of millions of Indians both Muslims and non-Muslims has survived for two hundred years in spite of several odds. Right from the beginning Urdu espoused nationalist sentiments amongst its readers and was completely anti-colonial and anti-imperialist in its treatment of the government of the day.

Also read:Explainer: What is fueling India's wholesale inflation?

From its infancy in 1822, Urdu newspapers and journalists forged nationalist sentiments through their reporting and articles. Hindus and Muslims shared the ownership and editorial responsibilities equally in the initial phase of the Urdu journalism. Promoting Indian nationalist ideals and negating anti-colonialist narratives was the foremost duty of the Urdu journalists. As the Persian newspapers of West Bengal were forerunners of the Urdu press, a language, which was patronised by the Mughal court and adopted by the ruling elite of the country, they focused on Urdu after the colonial masters ignored Persian in favour of English.

Pandit Harihar Dutta founded Jam-i-Jahan Numa, in 1822 in Kolkata (then Calcutta). He was the son of Pandit Tara Chand Dutta, an eminent Bengali journalist and one of the founders of the Bengali weekly Sambad Koumudi. The editor of this three-page weekly paper was Pandit Sadasukh Lal. It was the third language newspaper in India after English and Bengali, and was published till 1888.

After the unsuccessful revolt of 1857, Urdu journalism continued with its nationalistic fervour, as Urdu seemed to be the only language, which could play the role of a bridge between the nationalist leaders of emerging political parties in India and the common reader. However, after 1857, the centre of Urdu journalism shifted first to Lucknow and then Delhi from Kolkata. In spite of this various centres of Urdu journalism were present in almost all states of India, like Hyderabad, Chennai, Bengaluru, Mumbai, Patna, Bhopal and Srinagar, some of the current oldest dailies were started from these cities.

From 1857 onwards, Urdu journalism entered a new era of development under the patronage of all communities of India. An example is Oudh Akhbar, which was published from Lucknow by Munshi Nawal Kishore, under the editorship of Ratan Nath ‘Sarshar'. From the beginning of the 20th century, politics and social reforms dominated Urdu journalism. The political and social-reform movements launched by the Congress, the Muslim League, the Hindu Mahasabha, the Arya Samaj, the Khilafat Committee and the Aligarh Movement, exercised a profound influence on Urdu language newspapers and periodicals. All these movements started various Urdu newspapers to propagate their thinking amongst the masses.

In 1919, Mahashey Krishnan started Daily Pratap from Lahore. It vigorously supported Gandhi's policies and the Indian National Congress. It faced continuous government harassment and had to cease publication several times. It had great influence among the Urdu reading Hindus of Punjab and Delhi. However, after independence it changed tone and become pro-Hindu to a large extent.