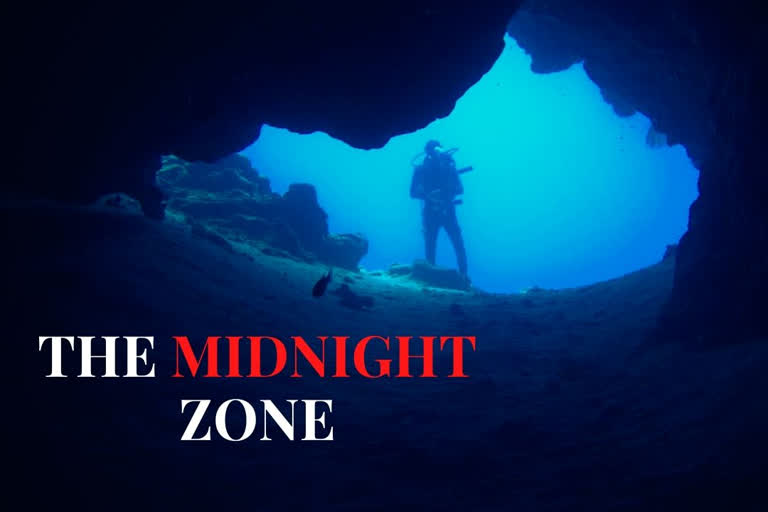

Mediterranean Sea: Within the next few days, scientists from the British-led Nekton Mission will begin their five-week expedition in the Indian Ocean into a 'Midnight Zone' where light barely reaches, but life still thrives.

Working with the Seychelles and Maldives governments, they'll be targeting seamounts - vast underwater mountains that rise thousands of metres from the seafloor.

To explore such inhospitable depths, Nekton scientists will board one of the world's most advanced submersibles, called 'Limiting Factor'.

Last August, the suitcase-shaped sub completed the Five Deeps Expedition, diving to the deepest point in each of the world's five oceans.

The deepest was almost 11,000 metres (36,000 feet) down - deeper than Mount Everest is tall.

"If you accept that the deep ocean is the largest biological habitat on earth, and we only have this one vehicle, this one pathfinder, that can actually get down to the lower half of it. This is the key, this is the vehicle that will unlock the secrets to the Hadal Zone," says Rob McCallum, expedition leader on the Pressure Drop mothership.

The Hadal Zone is the deepest region of the ocean, between 6,000 and 11,000 metres.

Read more:Watch magical Christmas light show at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew

To withstand such crushing pressures, the sub's two-person crew compartment is wrapped in a nine-centimetre (3.5-inch) titanium cocoon. It also carries up to 96 hours' worth of emergency oxygen.

"It's a very inhospitable environment, that pressure does represent significant threat," says mission director Oliver Steeds.

"If there was a catastrophic failure to the pressure hull and there was water ingress, the water could come through at such power because of that pressure to atomize you in a nanosecond," he said.

Using sampling, sensor and mapping technology, scientists expect to identify new species and towering seamounts, as well as observe man-made impacts, such as climate change and plastic pollution.

"We need to keep us nice and warm, so there's gonna be some insulation as well. And make sure, of course, there's oxygen for us to breathe. Of course, there's no air down there either," explains Nekton principal scientist Lucy Woodall.