Kabul (Afghanistan): The Taliban-appointed supervisor of a small district hospital outside the Afghan capital has big plans for the place — to the dismay of the doctors who work there.

Mohammed Javid Ahmadi, 22, was asked by his superiors, fresh off the fields of battle from a war that has spanned most of his life, what kind of jobs he could do. On offer were positions in an array of ministries and institutions now under the Taliban's power following their August takeover and the collapse of the former government.

It was Ahmadi's dream to be a doctor; poverty had kept him from gaining admission to medical school, he said. He chose the health sector. Soon after, the Mirbacha Kot district hospital just outside of Kabul became his responsibility.

"If someone with more experience can take this position it would be better, but unfortunately if someone (like that) gets this position, after some time you'll see that he might be a thief or corrupt," he said, highlighting a perennial problem of the former government.

It's a job Ahmadi takes very seriously, but he and the other health workers in the 20-bed hospital rarely see eye-to-eye. Doctors are demanding overdue salary payments amid critical shortages of medicine, fuel and food. Ahmadi's first priority is to build a mosque inside the hospital quarters, segregate staff by gender and encourage them to pray. The rest will follow according to the will of God, he tells them.

The drama in Mirbacha Kot is playing out across Afghanistan's health sector since the Taliban takeover. With power changing hands overnight, health workers have had to contend with a difficult adjustment. The host of problems that preceded the Taliban's rise were exacerbated.

The U.S. froze Afghan assets in American accounts shortly after the takeover, in line with international sanctions, crippling Afghanistan's banking sector. International monetary organizations that once funded 75% of state expenditures paused disbursements, precipitating an economic crisis in the aid-dependent nation.

Health is acutely affected. World Bank allocations funded 2,330 out of Afghanistan's 3,800 medical facilities, including the salaries of health workers, said the Taliban's Deputy Health Minister Abdulbari Umer.

Wages had been unpaid for months before the government collapsed.

Also read:WFP warns of growing starvation in Afghanistan

"This is the biggest challenge for us. When we came here there was no money left," said Umer. "There is no salary for staff, no food, no fuel for ambulances and other machines. There is no medicine for hospitals; we tried to find some from Qatar, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, but it's not enough."

In Mirbacha Kot, doctors have not been paid in five months.

Disheartened staff continue to attend to up to 400 patients a day, who come from the neighbouring six districts. Some have general complaints or a heart condition. Others bring sick babies.

'What can we do? If we don't want to come here there's no other job for us. If there was another job, nobody can pay us. It's better to stay here," said Dr Gul Nazar.

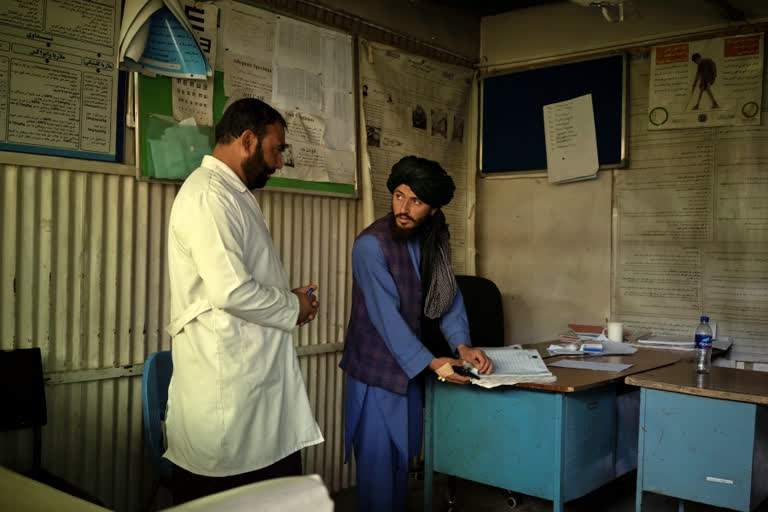

Every morning, Ahmadi makes his rounds. His small frame, topped by a black turban, is a sharp contrast to the sea of white coats that routinely rush in and out of the facility to tend to patients.

The first order of the day is the registration book. Ahmadi wants every doctor to sign in and out. It's a formality most health workers are too busy to remember, but neglecting it is enough to inspire Ahmadi's ire.

Second, the mosque.

Workers come to the hospital to take measurements for the project and Ahmadi gives them orders.

"We are Muslims, and we have 32 staff members, and for them, we need a mosque," he said.

There are many benefits, he added. Relatives can stay with sick patients overnight, sleeping in the mosque, as the hospital lacks extra beds especially during the winter months. "And this is what is needed the most," he said.

Dr Najla Quami looked on, bewildered.