Fort Bragg (North Carolina):In the unlikely setting of the world’s most populated military installation, amid all the regimented chaos, you’ll find the Endangered Species Act at work.

Tracking the St. Francis Satyr Butterfly.

Tracking the St. Francis Satyr Butterfly in North Carolina. It's one of the planet's rarest butterfly species. There might be just 3,000 existing, and all at Fort Bragg in North Carolina (NC). They haven't gone extinct thanks to the Endangered Species Act, but there's not enough of them to survive without federal protection.

"Of all the places you'd think to see an endangered butterfly, I mean, why would it be this one place?," says Michigan State University biologist Nick Haddad.

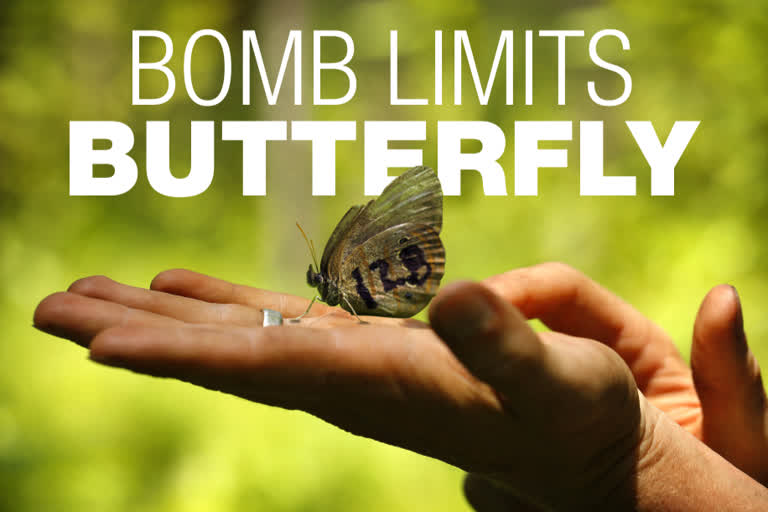

A St. Francis' satyr butterfly rests on a leaf in a swamp at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. The butterfly appears only twice a year for two weeks each time. When it does, Haddad rushes to Fort Bragg and joins a team of Army biologists to count the butterflies and improve their habitat such as installing giant inflatable rubber bladders that mimic beaver dams.

Read Also: US-born Bei Bei settles into new Chinese home

Fort Bragg biologist Brian Ball says military bases across the U.S. have turned into protected areas for species.

"Because they're areas where military trains, but there are also vast areas where the public is not there, there's no development. And a lot of rare species are actually on military installations," Ball says.

Soldiers prepare to leave a firing range at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. The St. Francis Satyr is among more than 1,600 U.S. species that have been protected by the Endangered Species Act signed by Republican President Richard Nixon in 1973. The law's successes are great, but many species linger on the list.

More than 99.2% of the species protected by the act survive. On the other hand, about 2% have made it off the endangered list because of recovery. Most of the species on the endangered list are getting worse. And only 8% are getting better, according to a 2016 study by Jake Li, director for biodiversity at the Environmental Policy Innovation Center in Washington.

Nick Haddad (left) watches a captive-bred female St. Francis' satyr butterfly fly off after it was released into the wild at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. After years of criticisms from conservatives that the endangered species program isn't working and is too cumbersome for industry and landowners, President Donald Trump's administration has enacted 33 different reforms.

Among them, a change in the rules for species that are threatened, the classification just below endangered. Instead of mandating, in most cases, they get the same protection as endangered species, the new rules allow for variations. The Trump Administration says that's better management.

A St. Francis' satyr butterfly is released after it was captured and marked biologist in a swamp at Fort Bragg in North Carolina "There's nothing in these changes that would make it easier to conserve species and in fact, some of the changes will make it harder to conserve species," says Li.

Even putting that aside, the act has its costs. About $3 million was spent to save the St. Francis Satyr butterfly. Another species found at Fort Bragg — the red-cockaded woodpecker — is another case of success but at a cost of $408 million over 19 years.

A St. Francis' satyr butterfly rests on sedge in swamp at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. The small woodpecker was among the first species given federal protection. They live only in longleaf pines which have been disappearing across the Southeast for more than a century due to the development and suppression of fires.

In the 1980s and 1990s, efforts to save the woodpecker and their trees set off a backlash among landowners who worried about interference on their private property.

A red-cockaded woodpecker is seen on a long leaf pine at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. Army officials weren't happy either. They were being told they couldn't train in many places because of the woodpecker.

"It attracted a lot of attention because it was so contentious," says Julie Moore, former Fish, and Wildlife Service woodpecker official.

But bureaucrats and biologists changed their approach.

Read Also: Hardy scientists trek to Venezuela's last glacier amid chaos

Instead of prohibiting work on land the woodpecker needs, Fish and Wildlife Service officials allowed landowners to make some changes as long as they generally didn't hurt the bird.

A red-cockaded woodpecker is held by a biologist collecting data on the species at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. The Army was able to resume training on the grounds and officials were convinced to set fires to regularly burn scrub.

The red-cockaded woodpecker may soon fly off the endangered list or, more likely, graduate to the less-protected threatened list.

A red-cockaded woodpecker prepares to enter its roosting cavity for the night in a long leaf pine forest in Southern Pines. "In my lifetime, I never thought that I was going to see woodpeckers survive. If it hadn't been for the Endangered Species Act... they would have been gone from every military installation and every national forest in the United States," says Moore.

A venomous cottonmouth snake moves over a small stream in close proximity to biologists working to improve habitat for the rare St. Francis' satyr butterfly, at Fort Bragg in North Carolina. The woodpecker is what's known as an umbrella species. What helps woodpeckers are good for the St. Francis Satyr butterfly and dozens of other vulnerable species.

"Now we're at a situation where we can see woodpeckers and butterflies together," says Haddad.

Read Also: Watch: Mountain gorilla numbers swell in Rwanda