Philadelphia: The seven justices who reversed Bill Cosby's conviction this week spent months debating whether he had a secret agreement with a prosecutor that tainted his 2018 criminal sexual assault conviction.

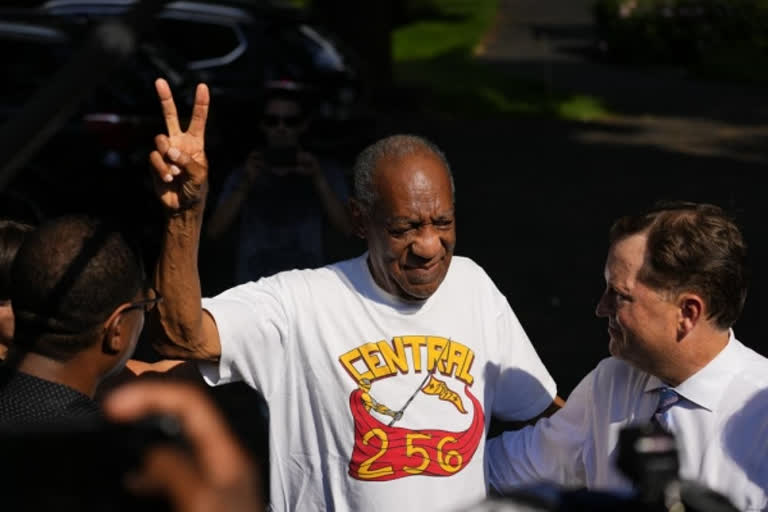

In the end, Pennsylvania's highest court ruled that a district attorney had induced Cosby to give incriminating testimony in 2005 for a lawsuit, with the promise that no criminal charges would be filed. Then, a decade later, another prosecutor used it against him a fundamental violation of his Fifth Amendment rights. America's Dad walked out of prison Wednesday and won't face any further trials in the case.

The public outcry over Cosby's sudden release three years into a potential 10-year sentence was swift, with #MeToo activists worried it would have a chilling effect on survivors. And lawyers for another high-profile man convicted of sexual assault, Harvey Weinstein, praised the decision. But criminal law experts believe the court acted reasonably in finding that a prosecutor's word should be honoured, even by a successor. One called the ruling a wakeup call for prosecutors who might try to quietly resolve a case without a paper trail, or make a deal over a handshake.

Read:Bill Cosby freed from prison, his sex conviction overturned

It probably would have been much better lawyering to get it all in writing, Loyola Law School professor Laurie Levenson, a former prosecutor, said of the hidden deal in the Cosby case. It's a teachable moment, I think, for prosecutors across the nation. It's a big lesson.

Levenson, too, fears the quick takeaway is that another celebrity gets away with a crime. More deeply, she said, the case illustrates the need for legal agreements that are open, fair and transparent. For survivors of sexual assault, it's got to be another incredibly upsetting, frustrating moment, she said. So (there are) good lessons for prosecutors and hard lessons for survivors.

The court heard arguments in December. On Wednesday, a majority of the justices, 6-1, found Cosby's case should be overturned. But the justices split 4-2 on whether he should go free or face a third trial. The two dissenting justices questioned if Cosby had ever really been promised immunity or whether an abuse of power led to former Montgomery County prosecutor Bruce Castor's odd and ever-shifting explanations of his promise to Cosby.

They urged their colleagues to condemn the tactics, lest others follow suit and make promises that later entrap defendants who agree to talk. We should reject Castor's misguided notion outright and declare that district attorneys do not possess this effective pardon power, Justice Kevin Dougherty wrote in a partial dissent.

Castor, testifying for the defense soon after Cosby's arrest in late 2015, said he had promised Cosby's lawyer in 2005 that the actor would never be charged over his encounter with Andrea Constand, in part so that he could help her wage a lawsuit against Cosby. No legal documents were drafted. No immunity agreements went before a judge. Even Castor's top assistant, who had led the initial investigation, said she knew nothing about it. Neither did Constand's lawyer, according to testimony at the sometimes surreal preliminary hearing in February 2016.

Castor said he discussed the agreement with a Cosby lawyer who had since died. And he said he issued a signed press release to announce the end of the investigation. Several courts have since parsed the wording of that press release, which opines that both parties in the case could be seen in a less than flattering light, and cautions that Castor would reconsider this decision should the need arise.

Constand, in the wake of that decision, sued Cosby in federal court. In the depositions that followed, the trailblazing actor made lurid admissions about his sexual encounters with a string of young women. He acknowledged giving them drugs or alcohol beforehand, while he stayed sober and in control. The list included Constand, who said she took what she thought were herbal products at Cosby's direction, only to find herself semiconscious on his couch.