No one expected Narasimha Rao to become the Prime Minister in 1991. Perhaps he was the last person to even entertain the thought of swearing in and occupying the position that was once occupied by Jawaharlal Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri and Indira Gandhi.

He did not contest the 1991 General Elections. As the election process began, it was widely believed that Rao was packing up his belongings and preparing to leave Delhi for Hyderabad.

What was even more unexpected and unpredictable was that he was to completely topple the economic edifice built by his illustrious predecessors over the years. In fact, Narasimha Rao was himself a strong votary of the Nehruvian doctrine of ‘socialistic pattern of society’ with the state occupying the ‘commanding heights of the economy’.

In one word, Narasimha Rao laid the foundation for the vibrant new India that we see around us today.

Narasimha Rao took momentous decisions in a matter of hours after he was sworn in as the PM. His most significant decision was to bring in Dr Manmohan Singh as his Finance Minister.

A domain expert with no political background, Singh, in Rao’s estimate was suitable to evoke confidence in the global financial players.

Rao gave Singh his full political backing so that the latter could go about his job with professionalism uninterfered by the day to day political compulsions.

In hindsight, it seems to us that all along Narasimha Rao was being groomed by destiny to preside over the fate of India and change its fortunes.

Rao was a person of uncommon erudition. He was well-read. Learnt over a dozen languages. He wrote poetry and fiction. He was a translator par excellence. He was a connoisseur of music. Had deep knowledge of Indian tradition and practices.

However, he was not someone who was trapped in orthodoxy. He was perhaps one of the few among his generation who was not only comfortable with the emerging Information Technology but had the mental capability to learn a couple of computer programming languages.

Rao did not tread the path of other learned and erudite politicians who chose an indirect route to the legislatures. He contested every general election that was held in India since independence except the 1991 elections.

Except for the first election, he was successful in every one of them. In 1984 although he lost in his native Andhra Pradesh, he was elected from a constituency in Maharashtra. He was perhaps one of the very few political leaders who always entered the legislatures through popular vote and who contested the largest number of elections until 1991.

All these facts are relevant for what happened during his tenure as Prime Minister. The economic reforms that he ushered in between 1991 and 1996 were in a way informed by his long experience in direct mass politics.

From the mid1950s to the mid-1970s he was in state politics as a legislator and served in successive state cabinets. He held a vast range of portfolios: from Law and Justice to Education to Endowments.

His career in the state peaked with his Chief Ministership. From the mid-1970s, he graduated into national politics. He held External Affairs, Defence, Human Resources Development, Home portfolios.

Both at the state level and national level Rao presided over some of the most important departments and ministries that are vital to understanding and transforming India.

His vast experience gave him an insight into the fabric of rural and urban life, and the country’s external relations.

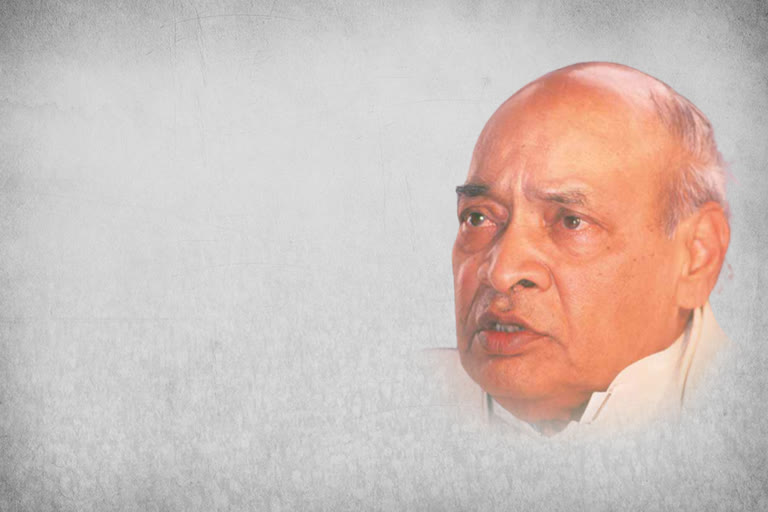

The man who redefined India's growth story

In this article, Parakala Prabhakar, who was close to late PM Narasimha Rao pays tribute to the only Telugu prime minister India ever had. Recognising, the reformist Rao's contribution, Telangana government will organise a year-long birth centenary celebrations of late former Prime Minister which will commence today across the state.

This background gave him a vantage position to watch the momentous changes that were sweeping the globe. The all too evident weakening of the planned economies of the socialist bloc, the turmoil in Soviet Russia, and the obsolescence of the socialist creed was apparent to him.

This is the intellectual equipment and practical experience that Narasimha Rao brought with him to the South Bloc when he took over as the PM in 1991. The country was staring at a deep economic crisis.

It had no sufficient foreign exchange reserves that could pay for even a week’s imports. We had to airlift our gold reserves to pledge to stay solvent. The country was on the brink of economic collapse.

A rigid doctrinaire approach to the crisis would have pushed the country into an economic abyss. Narasimha Rao showed his pragmatism at this critical juncture. Although a staunch supporter of Nehruvian economic philosophy with a socialist bent of mind throughout his career, Narasimha Rao quickly grasped what was demanded of him at that critical moment in the country’s history.

He read the writing on the wall clearly. He understood that if the country did not liberalise and allow its economy to be linked to the global market, there was no salvation for it.

He quickly moved to negotiate a deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF); agreed to devalue the Rupee; liberalised the trade regime and eased the internal restrictions on industrial policy.

Government control over investment decisions were relaxed. Private capital was freed from the shackles of Permit and license Raj.

In one stroke Rao did away with the Congress’s creed of ‘socialistic pattern of society’. The Industrial Policy Resolution of the 1950s was jettisoned.

However, his departure from ‘socialist path’ was not to lead India on to the road to the heartless and bare-knuckled capitalist path.

He, as a political leader with strong sense of ground realities, insisted that his reforms were ‘with a human face’; he wanted that those who were to face hardships in the short run to be provided with a ‘safety net’.

In fact, during his tenure, every speech of his had these two phrases prominently. In tandem with his liberalisation, he also focussed on rural development.

For the first time in India, Rural Development Ministry had seen an unprecedented steep rise in its budget allocations. Perhaps very few people remember that programmes like DWCRA were initiated during Narasimha Rao’s premiership.

The economic vision that he had articulated in 1991 remains unchallenged even today. After he demitted office in 1996 several governments were formed at the centre. Almost all political parties in the country either became a part of the government or supported successive governments from outside.

But none had deviated from his 1991 policy framework. Congress disowned him, humiliated him in his later years and in his death. But it could not reject his economic policies. BJP opposed him politically. But the governments led by that party did not deviate from his economic doctrine.

Interestingly, the man he picked up as his Finance Minister, Dr Manmohan Singh, has become his successor as Congress Prime Minister.

That goes to show the continuing relevance of his 1991 economic programme.

(This article is written by Parakala Prabhakar, a political commentator and economist with a doctorate from the London School of Economics)